| Posted: Aug 19, 2014 |

Watching nanoparticles swim

|

|

(Nanowerk News) Like sharks hunting their prey, soft nanoparticles should quickly navigate through the body's waters and attack cancerous cells, destroying the diseased tissue and leaving the rest alone. That's the goal. The challenge is understanding how the particle behaves in liquids, something most microscopes don't handle. Thanks to fortuitous discussions as part of the initial formation of the PREMIER Network, scientists studying the particles at the University of California at San Diego and the University of Pittsburgh teamed up with microscopists at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) and, together, they obtained clear images of the particles moving liquids ("Dynamics of Soft Nanomaterials Captured by Transmission Electron Microscopy in Liquid Water").

|

|

"The connection between the two teams came about through discussions surrounding the PREMIER Network," said Dr. Nigel Browning, network coordinator. The network, with more than 20 national labs and universities, facilitates innovative research using electron microscopy and related techniques.

|

|

Why It Matters

|

|

Some treatments for cancerous tumors are equally rough on nearby healthy breast, lung, or other tissues. Creating particles that drop tumor-destroying metals or designer drugs into affected cells -- but not healthy cells -- could help. To make this happen, scientists need to know how the particles behave in healthy and diseased cell fluids. This study shows that scientists can get sharp, real-time images of particles interacting in liquids using transmission electron microscopy. Other techniques require desiccation or freezing, making it impossible to study the cells interacting.

|

|

"This research is the first step in tracking how these nanoparticles evolve," said Dr. James Evans, a microscopy scientist at PNNL who worked on the study.

|

|

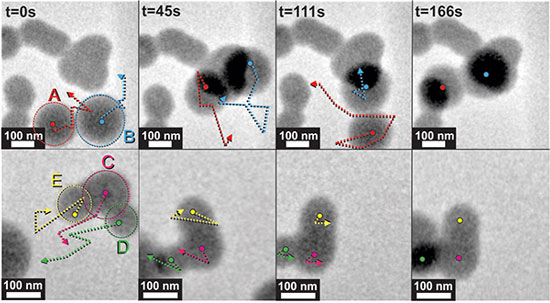

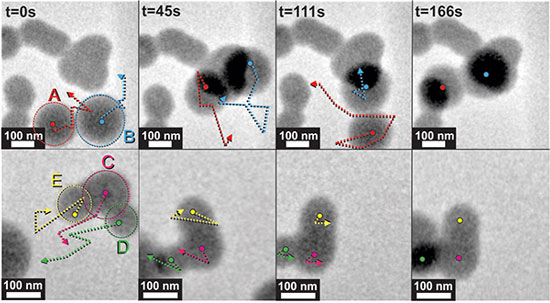

| The researchers obtained sharp images of nanoparticles swimming in water using an in-situ transmission electron microscope. The arrows indicate the direction of the particles during the time lapse. (Image: ©American Chemical Society)

|

|

Methods

|

|

When it came to studying the interactions of soft nanoparticles, made of lightweight elements such as carbon and nitrogen, scientists typically have a choice of freezing the particles or drying them out and staining them. Unfortunately, both approaches prevent them from studying the particles in motion, while staining could introduce troubling artifacts that changed the data.

|

|

Here, the scientists used an in-situ sample holder with extremely strong "windows" on the top and bottom. Drops of the nanoparticle-containing liquid were placed between the windows and loaded into a state-of-the-art transmission electron microscope. The sample stays fully hydrated because the windows protect it against the ultrahigh vacuum, and the microscope's electron beam then passes through the sample, providing data and images.

|

|

"To enable future viewing of drug release dynamics in action, we first needed to know if the sample could withstand the electron beam," said Evans. "It did."

|

|

What's Next? In the near term, the team will attempt to image particle evolution with high spatial and temporal resolution with a new dynamic transmission electron microscope that is currently under development at PNNL. In the meantime, the PNNL researchers are already analyzing other materials made from lightweight atoms. For example, they are learning how electrolytes behave to guide future battery studies or to test new electrolytes. Their work is winnowing the library of candidate solutions for further characterization and reducing the experimental time spent on less effective electrolytes.

|