| Posted: Aug 25, 2014 |

Biomimetic photodetector 'sees' in color

|

|

(Nanowerk News) Rice University researchers have created a CMOS-compatible, biomimetic color photodetector that directly responds to red, green and blue light in much the same way the human eye does.

|

|

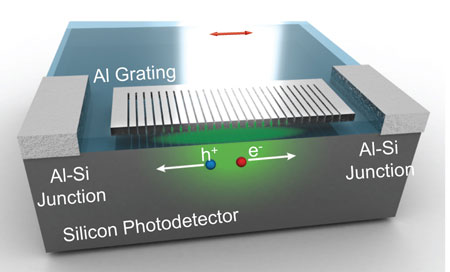

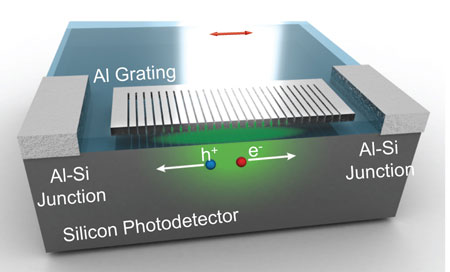

The new device was created by researchers at Rice’s Laboratory for Nanophotonics (LANP) and is described online in a new study in the journal Advanced Materials ("Color-Selective and CMOS-Compatible Photodetection Based on Aluminum Plasmonics"). It uses an aluminum grating that can be added to silicon photodetectors with the silicon microchip industry’s mainstay technology, “complementary metal-oxide semiconductor,” or CMOS.

|

|

| Researchers at Rice University's Laboratory for Nanophotonics have demonstrated a method for designing imaging sensors by integrating light amplifiers and color filters directly into pixels. (Image: B. Zheng/Rice University)

|

|

Conventional photodetectors convert light into electrical signals but have no inherent color-sensitivity. To capture color images, photodetector makers must add color filters that can separate a scene into red, green and blue color components. This color filtering is commonly done using off-chip dielectric or dye color filters, which degrade under exposure to sunlight and can also be difficult to align with imaging sensors.

|

|

“Today’s color filtering mechanisms often involve materials that are not CMOS-compatible, but this new approach has advantages beyond on-chip integration,” said LANP Director Naomi Halas, the lead scientist on the study. “It’s also more compact and simple and more closely mimics the way living organisms ‘see’ colors.

|

|

Biomimicry was no accident. The color photodetector resulted from a $6 million research program funded by the Office of Naval Research that aimed to mimic cephalopod skin using “metamaterials,” compounds that blur the line between material and machine.

|

|

Cephalopods like octopus and squid are masters of camouflage, but they are also color-blind. Halas said the “squid skin” research team, which includes marine biologists Roger Hanlon of the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Mass., and Thomas Cronin of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, suspect that cephalopods may detect color directly through their skin.

|

|

Based on that hypothesis, LANP graduate student Bob Zheng, the lead author of the new Advanced Materials study, set out to design a photonic system that could detect colored light.

|

|

“Bob has created a biomimetic detector that emulates what we are hypothesizing the squid skin ‘sees,’” Halas said. “This is a great example of the serendipity that can occur in the lab. In searching for an answer to a specific research question, Bob has created a device that is far more practical and generally applicable.”

|

|

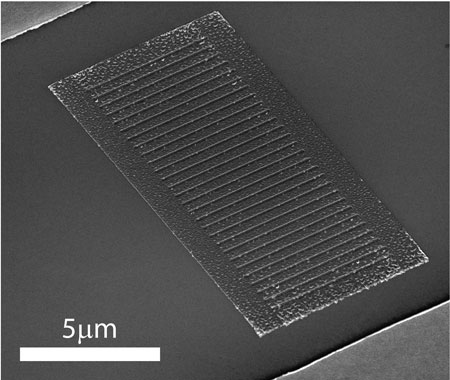

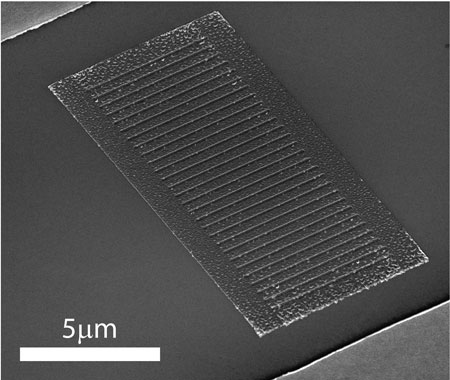

Zheng’s color photodetector uses a combination of band engineering and plasmonic gratings, comb-like aluminum structures with rows of parallel slits. Using electron-beam evaporation, which is a common technique in CMOS processing, Zheng deposited a thin layer of aluminum onto a silicon photodetector topped with an ultrathin oxide coating.

|

|

| The biomimetic color photodetector uses aluminum gratings like the one in this image from a scanning electron microscope. The light-filtering slits in the grating are about 100 nanometers wide. (Image: B. Zheng/Rice University)

|

|

Color selection is performed by utilizing interference effects between the plasmonic grating and the photodetector’s surface. By carefully tuning the oxide thickness and the width and spacing of the slits, Zheng was able to preferentially direct different colors into the silicon photodetector or reflect it back into free space.

|

|

The metallic nanostructures use surface plasmons — waves of electrons that flow like a fluid across metal surfaces. Light of a specific wavelength can excite a plasmon, and LANP researchers often create devices where plasmons interact, sometimes with dramatic effects.

|

|

“With plasmonic gratings, not only do you get color tunability, you can also enhance near fields,” Zheng said. “The near-field interaction increases the absorption cross section, which means that the grating sort of acts as its own lens. You get this funneling of light into a concentrated area.

|

|

“Not only are we using the photodetector as an amplifier, we’re also using the plasmonic color filter as a way to increase the amount of light that goes into the detector,” he said.

|