| Posted: July 24, 2009 |

Fluctuations in the levels of various molecules in the blood provide a reliable indicator of the body's internal clock |

|

(Nanowerk News) Without consciously checking your watch, your body knows the time by maintaining its own internal clock that tracks the day–night cycle through so-called circadian rhythms. Accordingly, disruption of these cycles, whether due to transient effects of jet-lag or disorders such as familial advanced sleep-phase syndrome, can profoundly affect an individual’s ability to maintain a normal pattern of sleeping and waking.

|

|

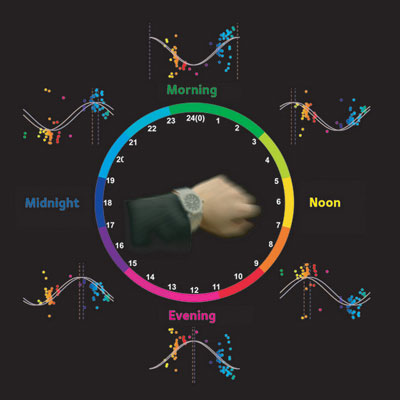

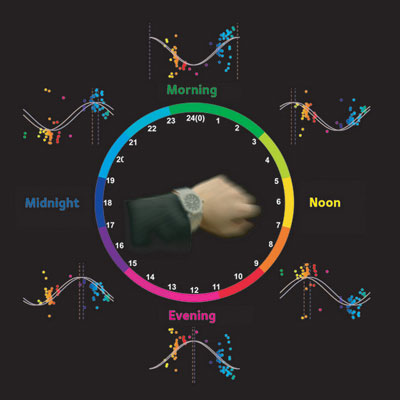

| Figure 1: Oscillations in the levels of a number of blood metabolites correlate directly with the passage of internal ’body time’ in mice. Each dot in this figure corresponds to an individual metabolite, and its color represents the peak time for that molecule relative to the central ’clock’.

|

|

Circadian rhythms also affect a number of other physiological activities, including manifestations of disease and the body’s response to therapeutics. “Interestingly, some cancer growth is under circadian clock control,” says Yoichi Minami of the RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology in Kobe. “This suggests that if we take drugs with precise timing, we can reduce unwanted effects.”

|

|

Inspired by the work of 18th Century botanist Karl Linné, who assembled a literal circadian clock composed of flower species that open and close their petals at specific times of day, Minami and colleagues Takeya Kasukawa, Yuji Kakazu, Tomoyoshi Soga and Hiroki Ueda recently set about constructing an analogous ‘body clock’ for mammals.

|

|

To achieve this, they applied sophisticated analytical chemistry techniques to characterize time-of-day-specific fluctuations in the levels of a broad variety of small molecules circulating in the mouse bloodstream ("Measurement of internal body time by blood metabolomics"). They performed their analysis with mice that were maintained either in fixed light–dark cycles, or in constant darkness, to distinguish variability resulting from external environmental time cues versus purely internal circadian timetables.

|

|

Depending on the analytical method applied, the researchers were able to detect between 150 and 300 compounds that appeared to show circadian regulation under both conditions. Once the oscillations of these various metabolites had been characterized, they were able to apply these patterns to determine the body-time at which a blood sample was collected (Fig. 1). Importantly, the accuracy of these measurements was not affected by differences in age, sex or food consumption, and the team was even able to directly observe relative shifts in the circadian clock resulting from simulated jet-lag.

|

|

|

|

These findings now clear the way for constructing an equivalent internal timetable for people. “One of our main goals is translation of circadian clock research from lab to clinic,” says Kasukawa. “If we can show the validity of our method in human beings … our method will contribute to the diagnosis of disease caused by circadian clock dysfunction [and] speed up development of circadian clock-conditioning drugs.”

|