| Posted: November 18, 2009 |

Researchers create 'fly paper' to capture circulating cancer cells |

|

(Nanowerk News) Just as fly paper captures insects, an innovative new device with nano-sized features developed by researchers at UCLA is able to grab cancer cells in the blood that have broken off from a tumor.

|

|

These cells, known as circulating tumor cells, or CTCs, can provide critical information for examining and diagnosing cancer metastasis, determining patient prognosis, and monitoring the effectiveness of therapies.

|

|

Metastasis — the most common cause of cancer-related death in patients with solid tumors — is caused by marauding tumor cells that leave the primary tumor site and ride in the bloodstream to set up colonies in other parts of the body.

|

|

The current gold standard for examining the disease status of tumors is an analysis of metastatic solid biopsy samples, but in the early stages of metastasis, it is often difficult to identify a biopsy site. By capturing CTCs, doctors can essentially perform a "liquid" biopsy, allowing for early detection and diagnosis, as well as improved treatment monitoring.

|

|

To date, several methods have been developed to track these cells, but the UCLA team's novel "fly paper" approach may be faster and cheaper than others — and it appears to capture far more CTCs.

|

|

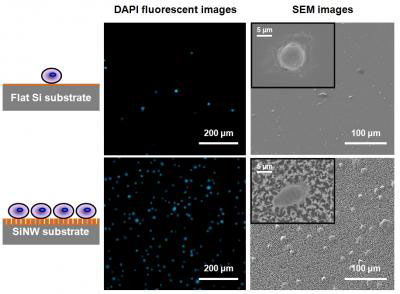

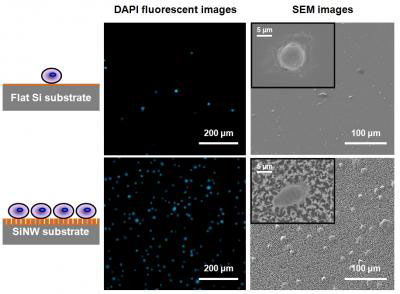

| Fluorescence micrographs and SEM images show how more cancer cells were captured on the silicon nanopillar (SiNP) substrate compared to the flat substrate.

|

|

In a study published this month in the journal Angewandte Chemie, the UCLA team developed a 1-by-2-centimeter silicon chip that is covered with densely packed nanopillars and looks like a shag carpet. To test cell-capture performance, researchers incubated the nanopillar chip in a culture medium with breast cancer cells. As a control, they performed a parallel experiment with a cell-capture method that uses a chip with a flat surface. Both structures were coated with anti-EpCAM, an antibody protein that can help recognize and capture tumor cells. The researchers found that the cell-capture yields for the UCLA nanopillar chip were significantly higher; the device captured 45 to 65 percent of the cancer cells in the medium, compared with only 4 to 14 percent for the flat device.

|

|

"The nanopillar chip captured more than 10 times the amount of cells captured by the currently used flat structure," said lead study author Dr. Shutao Wang, a postdoctoral researcher at both the Crump Institute for Molecular Imaging at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and the California NanoSystems Institute at UCLA.

|

|

Wang noted that the nano-size scale and the unique surface topography of the UCLA nanopillar chip may help it interact with nano-size components on cellular surfaces in the blood, enhancing capture efficiency.

|

|

The time required for CTC detection using CellSearch, a technology currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, is upwards of three to four hours, according to study author Dr. Hao Wang, a postdoctoral researcher at the Crump Institute and the California NanoSystems Institute at UCLA. The UCLA study found an optimal detection time of only two hours using nanopillar chips.

|

|

The nanopillar chip uses a common chamber slide, which fits into standard laboratory cell incubators. After the chip has been incubated and immunofluorescence-stained, an automated fluorescence microscope is used to identify and count the CTCs. The very simple device setting on the chamber slide allows multiple CTC detections to occur at the same time.

|

|

"We hope that this platform can provide a convenient and cost-efficient alternative to CTC sorting by using mostly standard lab equipment," said senior study author Dr. Hsian-Rong Tseng, associate professor of molecular and medical pharmacology at the Crump Institute and the California NanoSystems Institute.

|

|

The next step is more clinical research and possible studies with "break-away" cancer cells in patients' blood, as well as in other body fluids, such as urine and abdominal fluids, according to Tseng, who is also a researcher at UCLA's Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center.

|