| Posted: May 13, 2010 |

Molecular robots on the rise |

|

(Nanowerk News) Researchers from Columbia University, Arizona State University, the University of Michigan and the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) have created and programmed robots the size of single molecule that can move independently across a nano-scale track. This development, outlined in the May 13 edition of the journal Nature, marks an important advancement in the nascent fields of molecular computing and robotics, and could someday lead to molecular robots that can fix individual cells or assemble nanotechnology products.

|

|

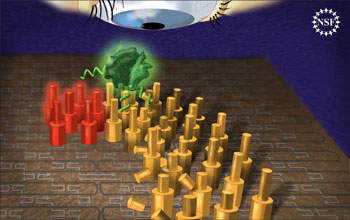

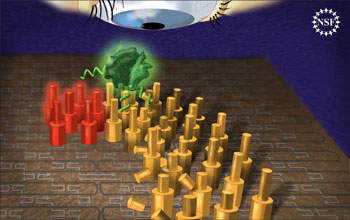

| Researchers have created and observed a molecular robot capable of many steps, and of making decisions where to step and how long to stay. As the robot walks on the substrate, it changes each piece by cleaving off a part. If it touches a spot that has been cleaved already, it does not linger as long. The end of the track glows red and captures the robot, letting the researchers know when it has completed its walk. The robot glows green, allowing for the researchers to see it better.

|

|

The project was led by Milan N. Stojanovic, a faculty member in the division of experimental therapeutics at Columbia University, who partnered with Erik Winfree, associate professor of computer science at Caltech, Hao Yan, professor of chemistry and biochemistry at Arizona State University and an expert in DNA nanotechnology, and with Nils G. Walter, professor of chemistry and director of the Single Molecule Analysis in Real-Time (SMART) Center at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Their work was supported in part by the National Science Foundation.

|

|

The word ‘robot' makes most people think of solid machines that use computer circuitry to perform defined jobs, such as vacuuming a carpet or welding together automobiles. In recent years, scientists have worked to create robots that could also reliably perform useful tasks, but at a molecular level. This is, needless to say, not a simple endeavor, and it involves reprogramming DNA molecules to perform in specific ways. "Can you instruct a biomolecule to move and function in a certain way--researchers at the interface of computer science, chemistry, biology and engineering are attempting to do just that," says Mitra Basu, a program director at NSF responsible for the agency's support to this research.

|

|

In recent years, scientists have been working to create robots that consist of a single molecule. Until recently, these robots have been able of only brief, directed motion on a one-dimensional track. Now a team of researchers have successfully created molecular robots capable of simple robotic actions within a defined environment autonomously, including the ability to start moving, turn, and stop. The researchers believe the process they have developed to achieve these tentative first steps may allow for more complex robotic behavior from these tiny robots. Milan Stojanovich, representing team of researchers from four institutions, discusses the team's work and its potential for future progress in this new field.

|

|

Recent molecular robotics work has produced so-called DNA walkers, or strings of reprogrammed DNA with 'legs' that enabled them to briefly walk. Now this research team has shown these molecular robotic spiders can in fact move autonomously through a specially-created, two-dimensional landscape. The spiders acted in rudimentary robotic ways, showing they are capable of starting motion, walking for awhile, turning, and stopping.

|

|

In addition to be incredibly small--about 4 nanometers in diameter--the walkers are also move slowly, covering 100 nanometers in times ranging 30 minutes to a full hour by taking approximately 100 steps. This is a significant improvement over previous DNA walkers that were capable of only about three steps.

|

|

While the field of molecular robotics is still emerging, it is possible that these tiny creations may someday have important medical applications. "This work one day may lead to effective control of chronic diseases such as diabetes or cancer," Basu says.

|

|

According to Stojanovich, these practical applications are still many years off, but he and his colleagues hope to continue their work in to the foundations of this young field. Stojanovich believes that their future work will also require extensive collaborations, with each of them bringing a specific expertise to the table, as was the case in the research published today. "If you take anyone of us with our disciplinary expertise out of this," Stojanovic said in an interview "this paper would have collapsed and never be what it is now."

|