| Posted: August 27, 2010 |

A new design for a gravimeter |

|

(Nanowerk News) Scientists have developed a novel design for a highly compact, ultra-sensitive quantum device to measure subtle changes in gravity over very short time or distance scales ("Interferometry with Synthetic Gauge Fields").

|

|

Tools of this sort – called atom interferometers (AIs) – are now used to search for natural resources beneath the Earth's surface, navigate deep underwater or in the air, and measure Newton's gravitational constant to extraordinary precision. But the new design, by researchers from the Joint Quantum Institute and its Physics Frontier Center, offers the possibility of unprecedented temporal resolution by harnessing the very recently demonstrated ability to create "synthetic" magnetic fields.

|

|

|

"The ability to measure gravity over fine time scales will help in finding oil fields and mineral deposits," says coauthor and JQI Fellow Victor Galitski. "Imagine an aircraft flying over an unexplored area. If heavy element deposits are hidden underneath, the gravimeter will react promptly by showing strong fluctuations in the local gravity field."

|

|

Atom interferometers rely on a counterintuitive but central precept of quantum mechanics: Everything, including matter – not just subatomic particles, atoms and molecules, but also macroscopic objects such as Buicks and buildings – has wave properties. Just like waves of light or sound, "matter waves" from different objects can interfere with one another constructively (reinforcement) or destructively (cancellation).

|

|

In addition, the new design takes advantage of yet another quantum phenomenon: "superposition," a condition in which objects have multiple values of the same property at the same time – the equivalent, in the classical world, of a ball that is simultaneously completely red and completely blue until someone looks at it. Once it is seen (or measured in any other way), however, the superposition disappears and the ball becomes either red or blue.

|

|

Conventional AIs exploit interference to measure gravity at a given location, typically by directing a stream of atoms into a beamsplitter, which divides the atoms' wave functions into two branches. Inside the device, each branch is propelled on separate – but completely symmetrical, mirror-image – paths down a cylinder. The only difference between the paths is that one is higher than the other – and therefore responds just slightly differently to the force of gravity. So when the two atom branches are recombined, their matter waves will be out of phase; and the amount of phase difference will be proportional to the difference in gravitational force felt by each.

|

|

Although useful, that method does not provide a good way to measure how gravitational force changes over small time periods and short length scales. And it necessarily requires the atoms to travel a relatively large distance, typically tens of centimeters, in order to produce a sufficiently large phase difference.

|

|

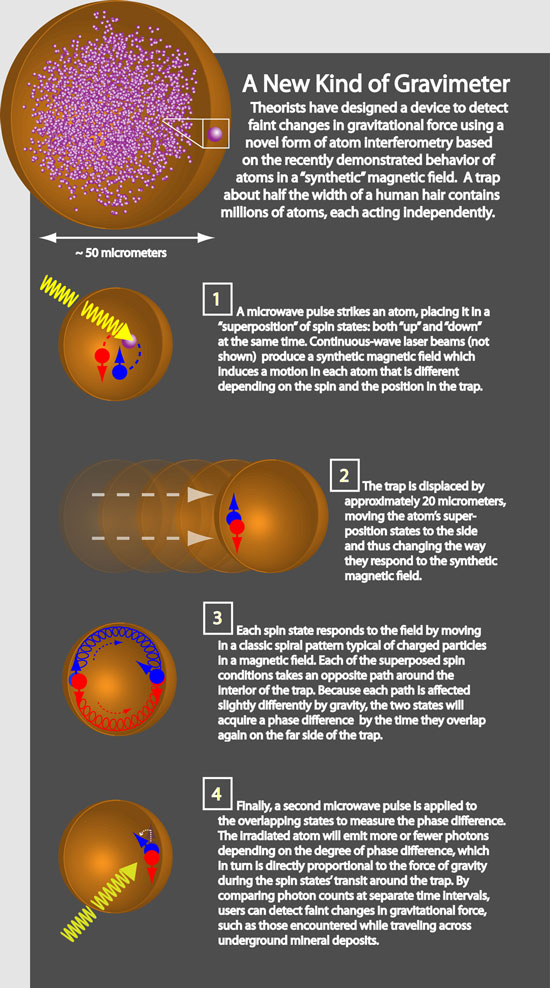

The JQI/PFC design, by contrast, uses an atom trap only 50 micrometers in diameter – about half the thickness of a human hair – containing millions of atoms chilled to a fraction of a degree above absolute zero. The atoms sit in a weak, inhomogeneous magnetic field, and each has a slightly different spin state (a kind of angular momentum) depending on its position in the field. The atoms are irradiated by a continuous-wave laser that imparts momentum to each atom, the magnitude and direction of which depends on the atom's spin state. This arrangement produces "synthetic" magnetism ("Synthetic magnetic fields for ultracold neutral atoms"), a condition which causes neutral atoms to behave as if they were charged particles in a real magnetic field.

|

|

"Recently, JQI researchers led by Ian Spielman have demonstrated that a synthetic magnetic field and synthetic spin can be created in cold-atom systems," says coauthor and JQI Fellow Jacob Taylor of the National Institute of Standards and Technology. "The proposed gravimeter setup is largely inspired by these amazing advances, and it uses the simplest possible configuration of replicas of a uniform synthetic field, which can be created easily in Spielman's experiment."

|

|

Then each atom is exposed to microwave radiation tuned to the specific wavelength that will project it into a "superposition" of two opposite spin states. [See Step 1 in the attached figure.] At that point, the trap is displaced by a small amount, about 20 micrometers, which has the effect of moving the atom, with its superposed states, into a different part of the synthetic field. [Step 2 in the figure.] Each of the two spin states starts to move in a spiral motion, but in opposite directions around the interior of the trap. [Step 3 in the illustration, also depicted in the short movie.] While in transit, each superposition state will be affected differently by gravity or any other acceleration. As a result, when their paths once again overlap at the end of their spiral trajectories, they will be slightly out of phase.

|

|

Finally, the atom is irradiated with a second microwave pulse [Step 4] that causes the atom to emit light if it is in a certain spin state, and to remain "dark" (no emission) if it is in another. If the superposed spin states had not experienced any external effects, such as gravity, each atom in the trap would have a 50-percent chance of emitting or not emitting. But if the paths of the spin states are affected by gravity, the collective output of the entire set of trapped atoms will emit more or less light – and the degree to which the light output varies is a measure of the strength of the gravitational field.

|

|

In addition to its potential practical uses, the new design can help test the fundamental laws of nature, such as Einstein's theory of relativity, which some believe maybreak down at very small time and length scales.

|