| May 09, 2011 |

3D proteins - getting the big picture (w/video)

|

|

(Nanowerk News) How do you get to know a protein? How about from the inside out?

|

|

If you ask chemistry professor James Hinton, "It's really important that students be able to touch, feel, see ... embrace--if you like, these proteins."

|

|

For decades, with funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF), Hinton has used nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) to look at protein structure and function. But he wanted to find a way to educate and engage students about his discoveries.

|

|

"I have all of this equipment, I get a lot of information about the structure of proteins and peptides, but the one thing I didn't have was a very sophisticated way of looking at them," says Hinton, from his lab at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville.

|

|

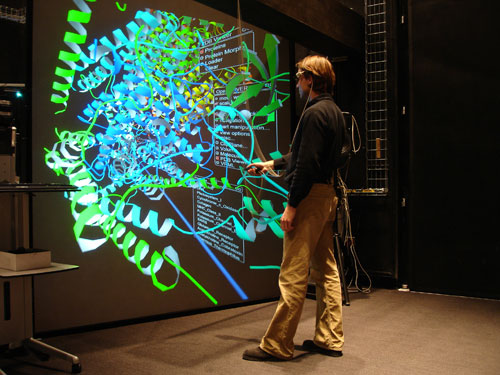

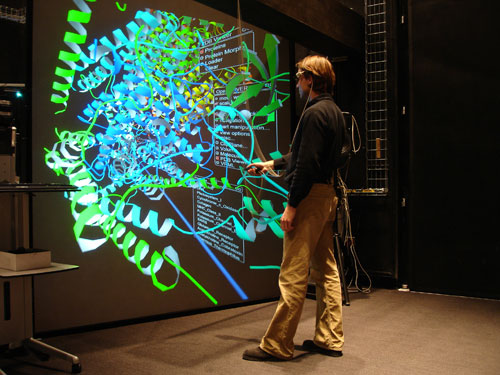

| This is an example of the interactive visualization of proteins from the Protein Data Bank (PDB), using PDB browser software on the C-Wall (virtual reality wall) at the California Institute for Telecommunications and Information Technology (Calit2) at the University of California, San Diego. The work was performed by Jürgen P. Schulze, project scientist, in collaboration with Jeff Milton, Philip Weber and Professor Philip Bourne of the University of California, San Diego. The software supports collaborative viewing of proteins at multiple sites on the Internet.

|

|

About five years ago, he realized there's a big difference between students looking at a drawing of a protein in a textbook and letting them "jump into" a three-dimensional display of these complex biochemical structures.

|

|

"Kids are visual people nowadays; they like to see things," says Hinton. "So I began to look around for ways of actually visualizing three-dimensional structures, and I came upon this idea of, 'Wouldn't it be nice if we had immersive techniques that would allow us to experience 3-D virtual reality?'."

|

|

With support from the Arkansas Bioscience Institute (ABI), Hinton worked with Virtalis, a company in Britain, to create an immersive 3-D virtual reality experience for studying proteins. The results have been dramatic.

|

|

"It's beginning to have a major impact on how we teach, and it is a great tool for students entering the fields of chemistry and biochemistry," notes Hinton.

|

|

"Proteins are chemical entities; they pretty much do all the work in your body," says graduate student Vitaly Vostrikov. "The problem with proteins is that they are three-dimensional entities. Visualizing them in two dimensions, on a sheet of paper, is pretty complex."

|

|

"Pretty complex" could sometimes mean tedious and frustrating for Vostrikov and many researchers studying proteins.

|

|

"Generally, when you have a protein that is of biological interest, and you want to understand the function, or to alter its activity, the first thing to do is to have the structure of the protein. Once you have the structure, you can understand what the protein looks like. For example, if it has to bind with other molecules, where do the molecules bind? Can we make binding stronger? Can we make binding weaker? Can we disrupt the binding site at all?" explains Vostrikov.

|

|

Donning a pair of 3-D glasses, he demonstrates how the immersive virtual reality display could show these structures. He could dive in and out of DNA, strains of the flu, and hemoglobin. The technology makes it possible to zoom in, zoom out, or rotate the structure; or look at components one by one.

|

|

"Understanding protein function is essential if you want to do something in pharmaceutical chemistry," adds Vostrikov.

|

|

Drug companies, universities and medical schools in the United States, Britain and Canada are using the technology. "We've had radiology groups come in, interested in imaging, of course, and the ability to do virtual reality on the human body," says Hinton.

|

|

Even people in non-scientific fields are using these imaging techniques.

|

|

"Other people have been in, including a group from Walmart. They're interested in building new stores, but it's far better to build a store in virtual reality, make your mistakes there, than break ground and start building," says Hinton.

|

|

His colleague, Paul Adams, assistant professor of chemistry and biochemistry at the University of Arkansas, says virtual reality has become an important tool for his work as well.

|

|

Adams studies abnormally functioning proteins, with the aim of learning more about the spread of cancer cells.

|

|

"I believe visualization is the epitome of trying to examine what differences among biomolecules could be the cause or the reason for them functioning in different ways and different environments," says Adams.

|

|

|

|

He says both his research and his teaching have been enhanced using the immersive 3-D virtual reality. In addition, these dramatic displays invite academic cooperation.

|

|

"If you think of interdisciplinary approaches, such as the work of a biologist, or a chemist, or a physicist: All three scientists could look at this technology, and see three different things, to come up with different ideas based on what they are seeing. And so I think that immersive technology could be a potentially novel way to interject interdisciplinary collaboration," explains Adams.

|

|

Hinton is 72 years old, and says he's "just an old man having fun." He and others at the university use a demo tape of the 3-D virtual reality as a recruiting tool. It's just the spark some young people need.

|

|

"Seeing them have fun is a great joy 'cause you feel maybe one out of these 100 or so kids will say, 'Well, biochemistry or, hmm ... chemistry, maybe I'd like that'," says Hinton.

|

|

Hinton has high praise for his students, many of whom have been supported by NSF. Immersive 3-D virtual reality allows the students, in their quest to solve real world problems, the opportunity to view their world in a different way.

|