| Aug 23, 2011 |

Controlling magnetism with electric fields

|

|

(Nanowerk News) An international team of researchers from France and Germany has developed a new material which is the first to react magnetically to electrical fields at room temperature. Previously this was only at all possible at extremely low and unpractical temperatures. Electric fields are technically much easier and cheaper to produce than magnetic fields for which you need power guzzling coils. The researchers have now found a way to control magnetism using electric fields at "normal" temperatures, thus fulfilling a dream.

|

|

The high-precision experiments were made possible in a highly specialized measuring chamber built by the Ruhr-Universität Bochum at the Helmholtz Centre in Berlin. The research group from Paris and Berlin with the participation of RUB scientists reported on their findings in Nature Materials ("Interface-induced room-temperature multiferroicity in BaTiO3").

|

|

ALICE in wonderland

|

|

The "multiferroic" property of the new material was demonstrated in the measuring chamber ALICE – so called because, like "Alice in wonderland" it can look beneath the surface of things. Here a specific range of X-rays is used to study magnetic nanostructures. The measuring chamber, developed by Bochum's physicists and funded by the Federal Ministry for Education and Research, has successfully been in use since 2007 at the electron storage ring BESSY II in Berlin. With the newly discovered material properties of BaTiO3 (bismuth-titanium oxide), in future it will be possible to design components such as data storage and logical switches that are controlled with electric instead of magnetic fields.

|

|

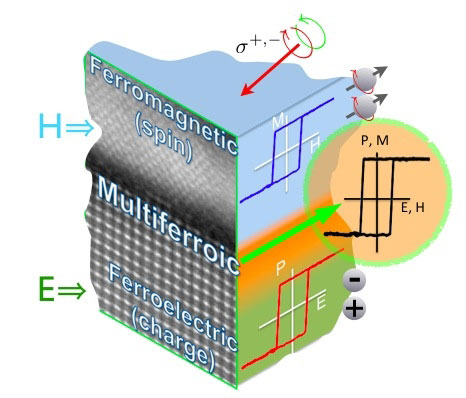

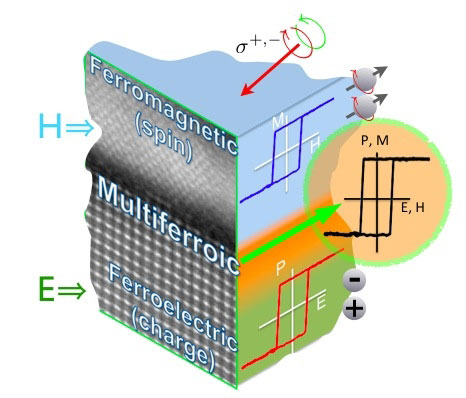

| Schematics of the sample sequence: on top the ferromagnetic Fe-layer, at the bottom the ferroelectric Bi-Ti-O layer, and in between the multiferroic layer. All three layers are characterized by their respective hysteretic response, i.e. the change of state in response to an external electric field (E) or magnetic field (H): the Fe-layer by a ferromagnetic hysteresis, the Bi-Ti-O layer by a ferroelectric hysteresis, and the response of the multiferroic interlayer that reacts upon both, electric field and magnetic field. The red arrow indicates the direction of the incoming synchrotron beam, which can be chosen to be either right of left circularly polarized.

|

|

Ferromagnetic and ferroelectric properties

|

|

Ferromagnetic materials such as iron can be affected by magnetic fields. All atomic magnetic dipoles are aligned in the magnetic field. In ferroelectric materials, electric dipoles - two separate and opposite charges - replace the magnetic dipoles, so they can be aligned in an electric field. In very rare cases, so-called multiferroic materials respond to both fields - magnetic and electric.

|

|

Multiferroic at room temperature

|

|

The researchers produced this multiferroic material by vapour coating ultra-thin ferromagnetic iron layers onto ferroelectric bismuth-titanium oxide layers. In so doing, they were able to establish that the otherwise non-magnetic ferroelectric material becomes ferromagnetic at the interface between the two ferromagnetic layers. Thus, the researchers have developed the world's first multiferroic material that reacts to both magnetic and electric fields at room temperature.

|

|

Magnetic X-ray scattering throws light on new control mechanism

|

|

The scientists demonstrated this interfacial magnetism using the spectroscopic method "X-ray magnetic circular dichroism". In this method, the polarisation of the X-rays is affected by magnetism – in a way which is similar to the famous "Faraday effect" in optics. X-ray magnetic circular dichroism has the advantage that it can be applied to every single element in the material investigated. With this method, the researchers were able to show that all three elements in the ferroelectric material - bismuth, oxygen and titanium - react ferromagnetically at the interface to iron, although these atoms are otherwise not magnetic.

|

|

An extremely sophisticated method

|

|

"The method of X-ray magnetic circular dichroism is highly complex", said Prof. Dr. Hartmut Zabel, Chair of Experimental Physics at the RUB. The measuring chamber ALICE combines X-ray scattering with X-ray spectroscopy. "This is an extremely sophisticated and very sensitive method", explained Prof. Zabel. "The high precision of the detectors and all the goniometers in the chamber led to the success of the experiments conducted by the international measuring team."

|