| Dec 07, 2011 |

Counting atoms with glass fibre

|

|

(Nanowerk News) Glass fibre cables are indispensable for the internet – now they can also be used as a quantum physics lab. The Vienna University of Technology is the only research facility in the world, where single atoms can be controllably coupled to the light in ultra-thin fibre glass. Specially prepared light waves interact with very small numbers of atoms, which makes it possible to build detectors that are extremely sensitive to tiny trace amounts of a substance. Professor Arno Rauschenbeutel's team, one of six research groups at the Vienna Center for Quantum Science and Technology, has presented this new method in the journal Physical Review Letters ("Dispersive Optical Interface Based on Nanofiber-Trapped Atoms"). The research project was carried out in collaboration with the Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz, Germany.

|

|

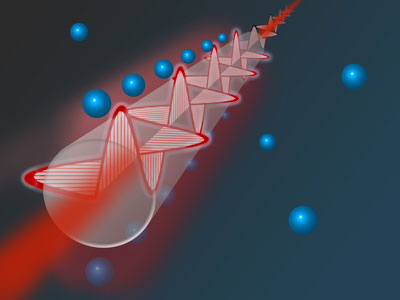

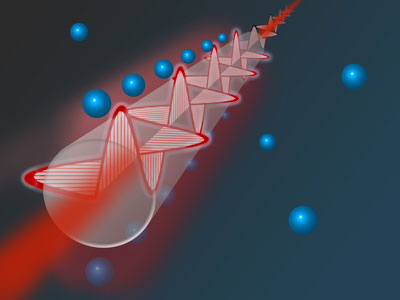

| The light wave in the glass fiber sticks out and touches the atoms trapped above and below the glass fiber.

|

|

Ultra-Thin Glass Fibres

|

|

The glass fibres used for the experiment are only five hundred millionths of a millimeter thick (500 nm). In fact, they are even thinner than the wavelength of visible light. "Actually, the light wave does not really fit into the glass fibre, it sticks out a little", Arno Rauschenbeutel explains. And this is precisely the big advantage of the new method: the light wave touches atoms which are located outside of, but very close to, the glass fibre. "First, we trap the atoms, so that they are aligned above and below the glass fibre, like pearls on a string", says Rauschenbeutel. The light wave sent through the glass fibre is then modified by each individual atom it passes. By measuring changes in the light waves very accurately, the number of atoms trapped near the fibre can be determined.

|

|

Atoms Change the Speed of Light

|

|

When scientists study the interaction of atoms and light, they usually look at rather disruptive effects – at least on a microscopic scale: Atoms can, for example, absorb photons and emit them later in a different direction. This way, atoms can be accelerated and hurled away from their original position. In the glass fibre experiments at Vienna UT however, a very soft interaction between light and atoms is sufficient: "The atoms close to the glass fibre decelerate the light very slightly", Arno Rauschenbeutel explains. When the light wave oscillates precisely upwards and downwards in the direction of the atoms, the wave is shifted by a tiny amount. Another light wave oscillating in a different direction does not hit any atoms and is therefore hardly decelerated at all. Light waves of different polarization directions are sent through the glass fibre – and their relative shift due to their different speed is measured. This shift tells the scientists how many atoms have delayed the light wave.

|

|

Detecting Single Atoms

|

|

Hundreds or thousands of atoms can be trapped, less than a thousandth of a millimeter away from the glass fibre. Their number can be determined with an accuracy of several atoms. "In principle, our method is so precise that it can detect as few as ten or twenty atoms", says Arno Rauschenbeutel. "We are working on a few more technical tricks – such as the reduction of the distance between the atoms and the glass fibre. If we can do this, we should even be able to reliably detect single atoms."

|

|

Non-Destructive Quantum Measurements

|

|

The new glass fibre measuring method is not only important for new detectors, but also for basic quantum physical research. "Usually the quantum physical state of a system is destroyed when we measure it", Rauschenbeutel explains. "Our glass fibres make it possible to control quantum states without destroying them." The atoms close to the glass fibre can also be used to tune the plane in which the light wave oscillates. Nobody can tell yet, which new technological possibilities may be opened up by that. "Quantum optics is an incredibly innovative research area today – and the Vienna research groups in this field are competing among the best in the world", says Arno Rauschenbeutel.

|