| Posted: Apr 10, 2006 |

|

Nanoparticles armed to combat cancer

|

|

(Nanowerk News) Ultra-small particles loaded with medicine – and aimed with the precision of a rifle – are offering a promising new way to strike at cancer, according to researchers working at MIT and Brigham and Women's Hospital.

|

|

In a paper, titled "Targeted nanoparticle-aptamer bioconjugates for cancer chemotherapy in vivo", published in the April 10, 2006 online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the team reports a way to custom design nanoparticles so they home in on dangerous cancer cells, then enter the cells to deliver lethal doses of chemotherapy. Normal, healthy cells remain unscathed.

|

|

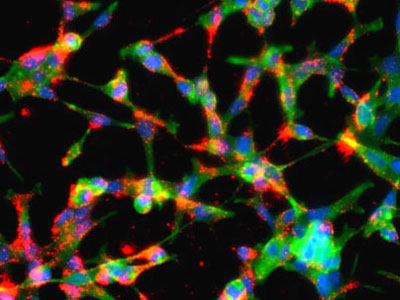

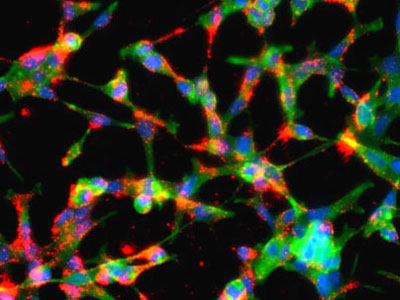

This image shows prostate cancer cells that have taken up fluorescently labeled nanoparticles (shown in red). The cells' nuclei and cytoskeletons are stained blue and green, respectively. Similarly designed targeted nanoparticles are capable of getting inside cancer cells and releasing lethal doses of chemotherapeutic drugs to eradicate tumors. (Source: Benjamin A. Teply, MIT)

|

|

The team conducted experiments first on cells growing in laboratory dishes, and then on mice bearing human prostate tumors. The tumors shrank dramatically, and all of the treated mice survived the study; the untreated control animals did not.

|

|

"A single injection of our nanoparticles completely eradicated the tumors in five of the seven treated animals, and the remaining animals also had significant tumor reduction, compared to the controls," said Dr. Omid C. Farokhzad, an assistant professor at Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

|

|

Farokhzad and MIT Institute Professor Robert Langer led the team of eight researchers. (Farokhzad was formerly a research fellow in Langer's lab.)

|

|

The scientists said that further testing is needed. Although all the parts and pieces of their new system are known to be safe, the system itself must yet be proven safe and effective in humans. This means thorough testing must be done in larger animals, and eventually in humans.

|

|

"We're most interested in developing a system that ends up in the clinic helping patients," Farokhzad said. To make that happen, he added, "we brought in cancer specialists and urologists to collaborate with us."

|

|

Further, he said, from an engineering perspective "we wanted to develop a broadly applicable system, one that other investigators can alter for their own purposes."

|

|

For example, Langer said, researchers "can put different things inside, or other things on the outside, of the nanoparticles. In fact, this technology could be applied to almost any disease" by re-engineering the nanoparticles' properties. The nanoparticles work like a bus that can safely carry different passengers to different destinations.

|

|

In the study, Farokhzad, Langer and colleagues tailor-made tiny sponge-like nanoparticles laced with the drug docetaxel. The particles are specifically designed to dissolve in a cell's internal fluids, releasing the anti-cancer drug either rapidly or slowly, depending on what is needed. These nanoparticles were purposely made from materials that are familiar and approved for medical applications by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Thus all of the ingredients are known to be safe.

|

|

Also, to make sure only the correct cells are hit, the nanoparticles are "decorated" on the outside with targeting molecules called aptamers, tiny chunks of genetic material. Like homing devices, the aptamers specifically recognize the surface molecules on cancer cells, while avoiding normal cells. In other words, the bus is driven to the correct depot.

|

|

In addition, the nanoparticles also display polyethylene glycol molecules, which keep them from being rapidly destroyed by macrophages, cells that guard against foreign substances entering the body.

|

|

The team chose nanoparticles as drug-delivery vehicles because they are so small that living cells readily swallow them when they arrive at the cell's surface. Langer said that particles larger than 200 nanometers are less likely to get through a cell's membrane. A nanometer is one-billionth of a meter.

|

|

The Farokhzad-Langer team created particles that are about 150 nanometers in size: a thousand sitting side by side might equal the width of a human hair.

|

|

Additional authors of the new paper are Jianjun Cheng, a former postdoctoral fellow with Langer now at the University of Illinois; Benjamin A. Teply of Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) and Harvard; Ines Sherifi, also at BWH and Harvard; Sangyong Jon, a former postdoctoral fellow with Langer now at the Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology in South Korea; Dr. Philip W. Kantoff of the Dana Farber Cancer Institute; and Dr. Jerome P. Richie of BWH and Harvard.

|

|

The research was supported, in part, by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) through the Harvard-MIT Center of Cancer Nanotechnology Excellence. The Harvard-MIT center is one of seven national Centers of Cancer Nanotechnology Excellence established recently by the NCI.

|