| Posted: January 30, 2008 |

Tiny magnets to repel drug counterfeiters |

|

(Nanowerk News) A large pharmaceutical packaging company is hoping that nanotech security tags devised by a small Singaporean firm will help it combat counterfeit drugs. India-based drug supplier Bilcare says it is in talks with Indian pharmaceutical companies to commercialise the nanoscale magnetic fingerprinting technology by Singular ID, a spin-out they bought for SGD 19.58 million ($14 million) earlier this month.

|

|

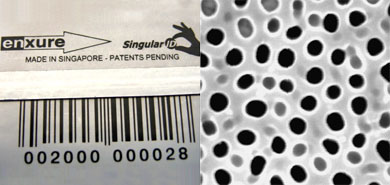

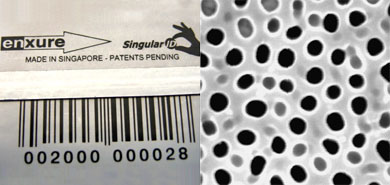

Singular ID's security tags are ceramic thin films dotted with irregular pores that are filled by 200nm wide magnets. Each film holds a randomly generated magnetic pattern that can be stored in a database: in essence, a unique fingerprint that is easy to manufacture but virtually impossible to copy.

|

|

According to Bilcare, Pfizer and other US-based pharmaceutical companies have also shown 'keen interest' in the system.

|

|

| Singular ID security tag (left) and pores in the ceramic film shown magnified 30,000 times (right) (Image: Singular ID)

|

|

Adrian Burden, Singular ID's CEO, told Chemistry World he hopes that within three to five years, pharmacies and patients will be able to trace the authenticity of their drugs using easy-to-operate scanners, rather like hole-in-the-wall or credit card machines. 'Pharmaceutical companies are always looking for more secure anti-counterfeiting technologies,' he said.

|

|

The World Health Organization estimates that 10 per cent of drugs sold worldwide are counterfeit. The fakes tend to be found in developing countries, or on the internet. In May last year, though, counterfeit batches of Roche's antiviral Tamiflu, Lilly's anti-psychotic Zyprexa, Sanofi-aventis' anticoagulant Plavix, and AstraZeneca's cancer drug Casodex were seized from the UK's wholesale chain.

|

|

The European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industry Associations wants medicines to be stamped with 2D barcodes, and AstraZeneca announced last year that it would be using them to authenticate supplies of Nexium, a blockbuster gastrointestinal drug.

|

|

There are plenty of other security options: holograms, tamper-resistant seals, watermarks, fluorescent dyes or inks, 2D bar codes, and radio-frequency identification (RFID) tags are just a few that can be combined. But as Burden argues, anything that can be seen by the human eye is liable to be copied; whereas anything that works on smaller scales may require specialised technology to read, and could be too slow for a point-of-sale check.

|

|

'And you always have to balance the level of technology against the cost of security - particularly for the pharmaceutical industry which produces such high volumes of drugs,' Burden pointed out. Many pharmaceutical companies have so far spurned RFID, for instance, because the price (at best 10 pence a chip) is too high. Burden reckons his company's magnetic tags could cost 1-2 pence each to make when produced in millions per day; and at fine resolutions, it is easier to read magnetic signals than optical signals at high speed, he says.

|

|

While such technologies could protect the brand reputation of big pharma companies, they won't do much to stop people buying unsafe drugs from street or internet suppliers, unless education about how to spot fake medicines is much improved, Burden acknowledges.

|