| Feb 04, 2013 |

A macromolecular shredder for RNA

|

|

(Nanowerk News) Much in the same way as we use shredders to destroy documents that are no longer useful or that contain potentially damaging information, cells use molecular machines to degrade unwanted or defective macromolecules. Scientists of the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry in Martinsried near Munich, Germany, have now decoded the structure and the operating mechanism of the Exosome, a macromolecular machine responsible for degradation of ribonucleic acids (RNAs) in eukaryotes. RNAs are ubiquitous and abundant molecules with multiple functions in the cell. One of their functions is, for example, to permit translation of the genomic information into proteins. The results of the studies now published in the journal Nature ("Crystal structure of an RNA-bound 11-subunit eukaryotic exosome complex") show that the structural architecture and the main operation mode of the Exosome are conserved in all domains of life.

|

|

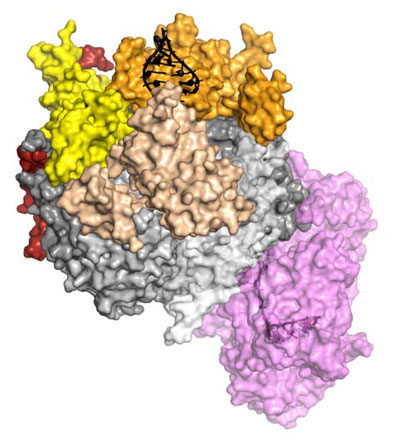

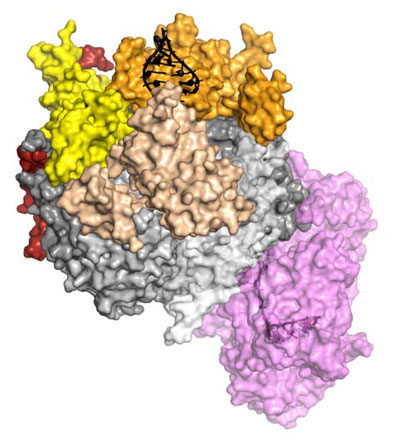

| The crystal structure of a complete eukaryotic RNA Exosome complex reveals how it recognizes and processes its substrate. RNA (black) is recognized and unwound by the cap proteins (yellow, beige, orange), threaded inside the barrel (gray) and targeted to the active site of the catalytic subunit (in violet), where processive degradation occurs. (Graphics: Debora L. Makino/ MPI of Biochemistry)

|

|

Any errors that occur during the synthesis of RNA molecules or unwanted accumulation of RNAs can be damaging to the cell. The elimination of defective RNAs or of RNAs that are no longer needed are therefore key steps in the metabolism of a cell. The Exosome, a multi-protein complex, is a key machine that shreds RNA into pieces. In addition, the Exosome also processes certain RNA molecules into their mature form. However, the molecular mechanism of how the Exosome performs these functions has been elusive.

|

|

A ubiquitous molecular shredder

|

|

Debora Makino, a postdoctoral researcher in the Research Department led by Elena Conti has now obtained an atomic resolution picture of the complete eukaryotic Exosome complex bound to an RNA molecule. The structure of this complex allowed the scientists to understand how the Exosome works. “It is quite an elaborate machine: the Exosome complex forms a hollow barrel formed by nine different proteins through which RNA molecules are threaded to reach a tenth protein, the catalytic subunit that then shreds the RNA into pieces,” says Debora Makino. The barrel is essential for this process because it helps to unwind the RNA and prepares it for shredding. “Cells lacking any of the ten proteins do not survive and this shows that not only the catalytic subunit but also the entire barrel is critical for the function of the Exosome,” Makino explains.

|

|

The RNA-binding and threading mechanism used by the Exosome in eukaryotes is very similar to that of the Exosome in bacteria and archaebacteria that the researchers had structurally characterized in earlier studies. “Although the chemistry of the shredding reaction in eukaryotes is very different from that used in bacteria and archaebacteria, the channeling mechanism of the Exosome is conserved, and conceptually similar to the channeling mechanism used by the Proteasome, a complex for shredding proteins,” says Elena Conti. In the future, the researchers want to understand how the Exosome is selectively targeted by the RNAs earmarked for degradation and how it is regulated in the different cellular compartments.

|