| May 17, 2013 |

The solution to natural cell imaging

|

|

(Nanowerk News) Most cells exist in a hydrated state and often live suspended in solution. In order to be imaged, cells must generally be frozen or dried, and then stained with substances such as heavy metals. Unfortunately, these processes can also alter the structure and chemical composition of the cells, resulting in inaccurate observations. Imaging the internal structures of whole, intact cells in their natural state has therefore been a particular challenge for scientists.

|

|

Changyong Song and colleagues from the RIKEN SPring-8 Center in collaboration with scientists from across Japan, Korea and the UK have now developed an x-ray diffraction microscopy method that allows whole, fully hydrated cells suspended in solution to be imaged for the first time ("Imaging Fully Hydrated Whole Cells by Coherent X-Ray Diffraction Microscopy").

|

|

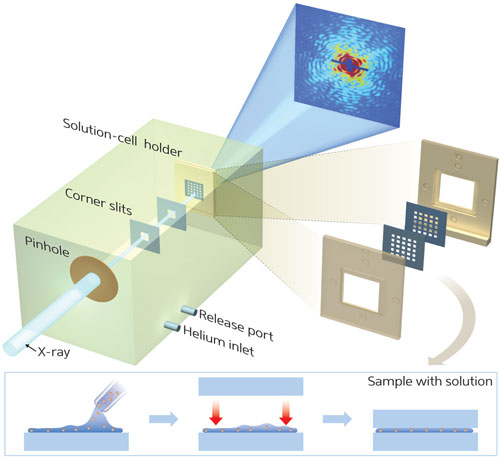

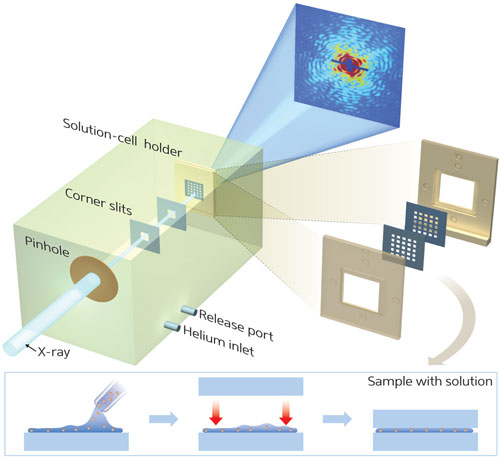

| Figure 1: By using membranes to hold a living cell in a uniformly thin layer of water, the ‘wet-CDI’ technique allows detailed nanoscale imaging of whole, fully hydrated cells in their natural state.

|

|

X-ray diffraction microscopy works by analyzing the wave distortion created when an x-ray hits an object—rather like the patterns generated when waves pass an object in water. Coherent diffraction imaging (CDI) utilizes these diffraction patterns to build up detailed images of objects at the nanometer scale.

|

|

Song and his team overcame the reservations of others in the field to successfully image hydrated objects suspended in water by CDI. “The CDI technique is very sensitive to the sample and its surroundings,” says Song. “Some researchers believed that the solution would produce significant noise, and that samples would hover around insecurely in solution. We sought to challenge this belief.”

|

|

The team developed a hydrated specimen holder comprising two very thin membranes between which whole, hydrated cells could be sandwiched in solution (Fig. 1). “A uniformly thin layer of water between the membranes does not produce noticeable diffraction signals,” explains Song. “The cells are held tightly in solution, and images are therefore exclusively from the fully hydrated cell samples.”

|

|

This ‘wet-CDI’ technique allowed the team to visualize cell morphologies and structures smaller than 25 nanometers in size, with no degradation in image quality. Wet-CDI could also easily be adapted for three-dimensional imaging.

|

|

“We expect wet-CDI to open a route to dynamic cellular imaging to chase developmental progress in cells at nanoscale resolutions,” says Song. “It can also be immediately adapted to newly established x-ray free-electron lasers such as SACLA at the RIKEN SPring-8 Center. This will allow us to take nearly radiation-free snapshots of living cells or organelles.”

|

|

Wet-CDI is a dramatic step forward in the quest to image whole cells in their natural state, and could have applications in such diverse fields as biology, medicine, materials science and petroleum research.

|