| Aug 07, 2012 |

Chemists advance clear conductive films

|

|

(Nanowerk News) In a touch-screen display or a solar panel, any conductive overlay had better be clear. Engineers employ transparent thin films of indium tin oxide (ITO) for the job, but a high-tech material’s properties are only half its resume. They must also be as cheap and easy to manufacture as possible. In a new study, researchers from Brown University and ATMI Inc. report the best-ever transparency and conductivity performance for an ITO made using a chemical solution, which is potentially the facile, low-cost method manufacturers want.

|

|

“Our technology is already at the performance level for application in resistive touch screens,” said Jonghun Lee, a Brown chemistry graduate student and lead author of the paper posted online Aug. 1 by the Journal of the American Chemical Society ("A Facile Solution-Phase Approach to Transparent and Conducting ITO Nanocrystal Assemblies").

|

|

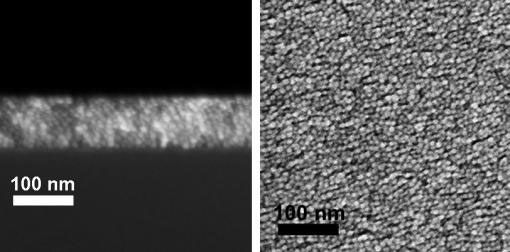

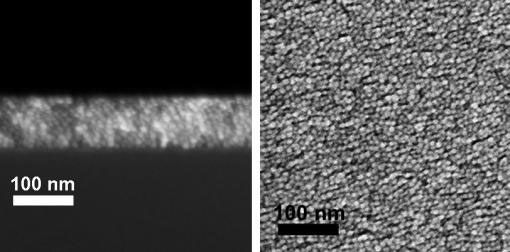

| Efficient manufacture and optimized conductivity. Electron microscopy (cross-section, left, and facing view) shows an even distribution of indium titanium oxide nanocrystals essential for a highly conductive, transparent thin film. (Image: Sun Lab/Brown University)

|

|

The group made conductive ITO films 146 billionths of a meter thick that allowed 93 percent of light to pass through, a transparency comparable to the glass plates they were deposited on. The team also made their films on top of bendable polyimide, showing that it could potentially be useful for making flexible display technologies.

|

|

In several experiments they showed that by varying the thickness and the tin content (between 5 and 10 percent was best) they could vary the transparency and resistance to find the best combination.

|

|

“By controlling the concentration of the nanocrystal solution, we could control the thickness of the film from 30 nanometers to 140 nanometers,” Lee said.

|

|

The solution

|

|

To make the films, the team synthesized nanoscale ITO crystals in a solution. Then they made a flat and smooth film of them by dripping the solution onto a glass plate followed by rapid spinning, a process called spin casting. From there they baked, or annealed, the coated plates for several hours (the best length of time turned out to be six hours) and then tested their transparency and conductivity.

|

|

Spin casting is simple as high-tech manufacturing processes go, but finding the chemistry that allows spin casting to produce a high-performance ITO thin film has proven elusive. A key achievement described in the new paper, was finding the materials needed to make the nanoscale ITO crystals in the first place, said Shouheng Sun, professor of chemistry at Brown and the study’s corresponding author.

|

|

The best chemicals turned out to be indium acetylacetonate and tin bis(acetylacetonate)dichloride. They synthesized ITO nanocrystals that had a narrow range of sizes, about 11 billionths of a meter in diameter. That consistency meant that when the crystals arranged themselves in the thin films, they neither bunched together in clumps, nor stayed too far apart. The result was a dense but evenly distributed array of crystals, which promotes conductivity.

|

|

“If the particle clumps, then you cannot get uniform assembly and you can’t get good conductivity,” Sun said.

|

|

This discovery was critical for achieving the high-level performance detailed in the paper, but the team knows it still needs to build on that progress — for instance, to match the conductivity performance of films made by a process called sputtering.

|

|

“The next step is to improve conductivity to a magnitude commensurate with sputtered ITO while realizing the reduced cost and process efficiency benefits expected of a solution-based ITO deposition method,” said Melissa Petruska, senior scientist at ATMI and co-author of the paper.

|

|

In new experiments, therefore, the team plans to further drive down electrical resistance, to reduce the length of time the films need to anneal, and to lay down fine patterns of their films, rather than continuous sheets, using inkjet or roll-to-roll printing.

|