| Dec 03, 2012 |

The self-improvement of lithium-ion batteries

|

|

(Nanowerk News) The search for clean and green energy in the 21st century requires a better and more efficient battery technology. The key to attaining that goal may lie in designing and building batteries not from the top down, but from the bottom up — beginning at the nanoscale. A team of researchers from Argonne National Laboratory and the University of Chicago has taken such an approach by developing titanium dioxide (TiO2) electrodes that can actually improve their own electrochemical performance as they are used.

|

|

The experimenters synthesized TiO2 nanotubes and assembled them into Li-ion coin cells, then cycled them galvanostatically between 0.8 V and 2.0 V. Electrode samples from the cells were then examined using x-ray diffraction (XRD) at the GeoSoilEnvirioCARS 13-ID-D insertion device beamline and x-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) at the X-ray Science Division 20-BM bending magnet beamline, both at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source at Argonne.

|

|

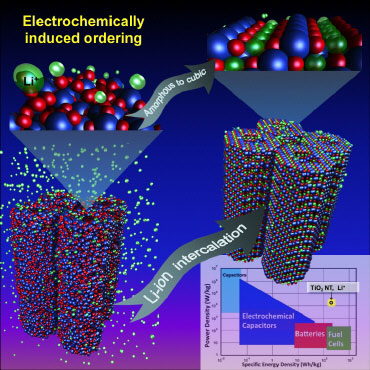

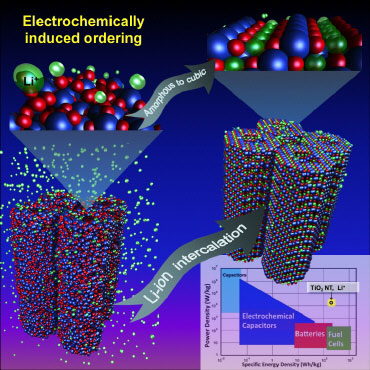

| Amorphous titanium oxide nanotubes, upon lithium insertion in a Li-ion battery, self-create the highest capacity cubic lithium titanium oxide structure.

|

|

In addition to the synthesis of the TiO2 nanotubes, scanning electron microscopy imaging and molecular dynamics simulations also were performed at the Argonne Center for Nanoscale Materials. All these techniques provided a window into the inclusion and removal of ions (intercalation/deintercalation process) occurring within the TiO2 nanotubes.

|

|

Using the amorphous nanoscale TiO2 nanotubes as an anode in lithium half-cells, the researchers noted a consistently linear decreasing voltage during the first discharge, followed by a “hump” at ~1.1 V vs Li/Li+. This indicated an irreversible phase transition in the nanotube material.

|

|

On subsequent cycles, Li+ ions reversibly intercalated/deintercalated into the TiO2 nanotubes with capacities far beyond those observed in other TiO2 varieties such as anatase.

|

|

The team concluded that this is due to a different structure or intercalation mechanism occurring as a result of the phase transition. Compared to anatase, the phase-transformed TiO2 nanotube anode displayed greatly improved Li-ion diffusion, especially at high cycling rates. The TiO2 nanotube anode demonstrated both much higher energy and higher power compared to its structural TiO2 cousins, which displayed a decrease in capacity in similar experiments using fast cycling.

|

|

The XRD and XAS studies, along with computational simulations, displayed how the anode structure changes upon cycling. Above ~1.1 V, no changes were observed with cycling, but below 1.1 V, a highly-symmetric, closely-packed cubic oxygen crystalline structure formed, with Ti and Li randomly distributed among octahedral sites.

|

|

Interestingly, the type of short-range order that would be expected in such a fully-ordered octahedral system apparently does not develop in this case. However, this does not affect thermodynamic stability, and the cubic structure remained both highly stable and reversible following the phase transition.

|

|

It appears that the intercalation/deintercalation of Li+ ions initiates a new structure that allows even better intercalation of Li+ ions. Because all layers of the new structure retain metal atoms even in the charged state, the cubic phase of the material is preserved. Molecular dynamics simulations of Li-ion diffusion in other types of TiO2 structures showed that the most efficient diffusion and the lowest activation barrier (0.257 eV) occurs in the amorphous cubic Li2Ti2O4 form, compared to other TiO2 varieties such as, again, anatase.

|

|

The amorphous-to-cubic TiO2 nanotube anode was tested in a full cell configuration with a 5-V spinel cathode (LiNi0.5Mn1.5O4<). On repeated cycling, the cell displayed an average voltage of 2.8 V and improving capacity.

|

|

Another distinct advantage of the TiO2 nanotube anode is that because it does not suffer capacity degradation, it avoids Li plating at the graphite anode and electrode over-potentials that create possible safety hazards in other types of Li-ion batteries.

|

|

By creating a nanoscale electrode material that can actually order itself into a more efficient and powerful electrochemical structure as it is subjected to repeated discharging and charging, the research team forged a new pathway for the design and development of higher capacity, higher power, safer batteries. In our world of smart phones technology and electric cars, the importance of such an advance can hardly be overestimated.

|