| May 15, 2013 |

Chain instead of zigzag: Physicists let magnetic dipoles interact on the nanoscale

|

|

(Nanowerk News) Physicists at the Ruhr-Universität Bochum (RUB) have found out how tiny islands of magnetic material align themselves when sorted on a regular lattice - by measurements at BESSY II. Contrary to expectations, the north and south poles of the magnetic islands did not arrange themselves in a zigzag pattern, but in chains. “The understanding of the driving interactions is of great technological interest for future hard disk drives, which are composed of small magnetic islands”, says Prof. Dr. Hartmut Zabel of the Chair of Experimental Physics / Solid State Physics at the RUB. Together with colleagues from the Helmholtz-Zentrum in Berlin, Bochum’s researchers report in the journal Physical Review Letters ("Magnetic Dipole and Higher Pole Interaction on a Square Lattice").

|

|

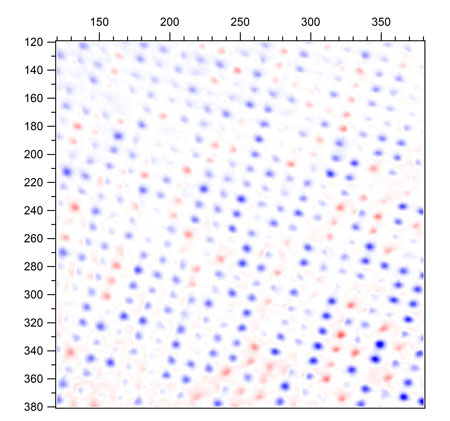

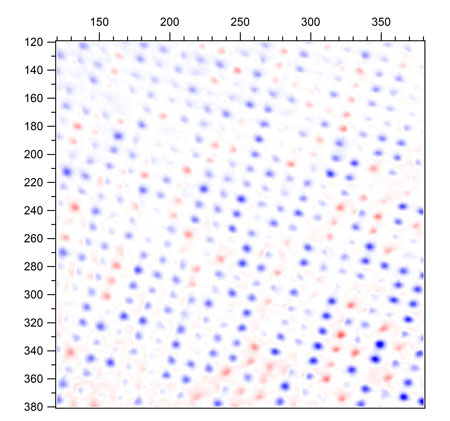

| Dipole chains: Photon emission electron micrograph of the magnetic state of magnetic islands at 140 Kelvin. In the blue-coloured islands, the magnetic dipoles point upwards along the lattice, in the red-coloured islands downwards. White islands have a dipole orientation which is perpendicular to the red and blue-coloured islands. The micrograph taken at 140 K was recorded at BESSY II of the Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin.

|

|

Complete chaos in the normal state

|

|

Many atoms behave like compass needles, that is, like little magnetic dipoles with a north and a south pole. If you put them close together in a crystal, all the dipoles should align themselves to each other, making the material magnetic. However, this is not the case. A magnetic material is only created when specific quantum mechanical forces are at work. Normally, the forces between the atomic dipoles are by far too weak to cause magnetic order. Moreover, even at low temperatures, the thermal energy causes so much movement of the dipoles that complete chaos is the result. “However, the fundamental question remains of how magnetic dipoles would align themselves if the force between them was big enough”, Prof. Zabel explains the research project.

|

|

Square lattice of magnetic islands

|

|

To investigate this, the researchers used lithographic methods to cut circular islands of a mere 150 nanometers in diameter from a thin magnetic layer. They arranged these in a regular square lattice. Each island contained about a million atomic dipoles. The forces between two islands were thus stronger by a factor of a million than that between two single atoms. If you leave these dipoles to their own resources, at low temperatures you can observe the arrangement that results exclusively from the interaction between the dipoles. They assume the most favourable pattern in terms of energy, the so-called ground state. The islands serve as a model for the behaviour of atomic dipoles.

|

|

Magnetic microscopy

|

|

The electron synchrotron BESSY II at the Helmholtz-Zentrum in Berlin is home to a special microscope, the photon emission electron microscope, with which the RUB physicists made the arrangement of the magnetic dipole islands visible. Using circularly polarised synchrotron light (X-ray photons), the photons stimulate specific electrons. These provide information on the orientation of the dipoles in the islands. The experiments were carried out at low temperatures so that the thermal movement could not interfere with the orientation of the dipoles.

|

|

Dipoles arrange themselves in chains

|

|

The magnetic dipoles formed chains, i.e. the north pole of one island pointed to the south pole of the next island. “This result was surprising”, says Zabel. In the lattice, each dipole island has four neighbours to which it could align itself. You cannot tell in advance in which direction the north pole will ultimately point. “In fact, you would expect a zigzag arrangement”, says the Bochum physicist. Based on the chain pattern observed in the experiment, the researchers showed that higher order interactions determine how the magnetisation was oriented. Not only dipolar, but also quadrupolar and octopolar interactions play a role. This means that a magnetic island exerts forces on four or eight neighbours at the same time.

|

|

Magnetic islands in the hard drives of the future

|

|

In future, hard disks will be made up of tiny magnetic islands (bit pattern). Each magnetic island will form a storage unit which can represent the bit states “0” and “1” - encoded through the orientation of the dipole. For a functioning computer, you need a configuration in which the dipole islands interact as little as possible and can thus assume the states “0” and “1”independently of each other. For the technical application, a precise understanding of the driving interactions between magnetic islands is therefore crucial.

|