| Jun 10, 2013 |

Nanotechnology explores the secret life of knots

|

|

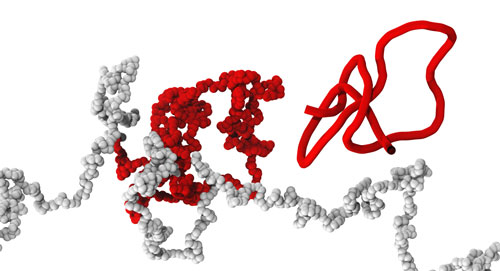

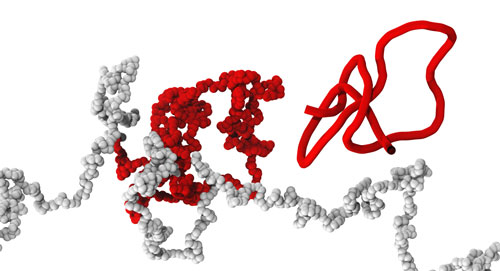

(Nanowerk News) Nanotechnologies require a detailed knowledge of the molecular state. For instance, it is useful to know when and how a generic polymer, a long chain of polymers (chain of beads), knots. The study of molecular entanglement is an important field of study as the presence of knots affects its physical properties, for instance the resistence to traction. Previous studies had mainly obtained “static” data on the knotting probability of such molecules. In other words, they focused on the likelihood that a polymer may knot. The novelty of the study ("Spontaneous Knotting and Unknotting of Flexible Linear Polymers: Equilibrium and Kinetic Aspects") carried out by Micheletti and colleagues lies in the fact that this time the dynamic aspect of the phenomenon has been simulated.

|

|

| Polymer entanglement

|

|

“It’s a little like the difference that lies between a disorganized collection of photographs and a video. With the former we obtain statistical information (for instance, how many times a knot will appear), but we don’t know how that situation occurred and how it will evolve”, explained Micheletti. “Thanks to dynamic simulation we have found, for instance, that knots tend to form at the ends, where they are very frequent yet ephemeral, that is, they are short-lived.”

|

|

According to the team’s observations, in fact, once formed the knot moves along the chain in an apparently casual manner, it may take a step to the left, then two to the right and so on, so that at the end of the chain it generally tends to disappear, “falling” outside the filament. Micheletti also explains that, although more infrequently, it has been observed that the knot moves towards the centre of the polymer: “When this occurs, the knots average lifetime is higher than when they remain trapped at the ends.”

|

|

At the center of the polymer also slip-knots or pseudo-knots, may form. “At first a loop is formed and this blocks another part of the filament. If thermal fluctuations pull to the correct side the knot disappears, while if they pull to the loop side, a proper knot may be created. These knots are very long-lived,” explains Rosa.

|

|

“This research is useful since the data on simple knotting probability reveal nothing about knotting timing”, underlines Tubiana. “If knots form and disappear very quickly, after a certain amount of time we may observe a given percentage of average knotting, yet we do not know whether the knots have remained the same or if they have changed through time. Researchers who carry out experiments of this kind need, instead, more detailed information.”

|

|

Cristian Micheletti will present these data on 10 June at Harvard University, in the United States, as one of the four speakers selected for the Engineering and Physical Biology Symposium 2013.

|