| Aug 14, 2014 |

Interstellar dust - each grain is different

|

|

(Nanowerk News) The space between the stars is not empty, but filled with interstellar matter – gas and dust particles. But all dust is not the same: An international team from 33 research institutes, including the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry in Mainz, discovered that the structure and chemical composition of interstellar dust particles collected by the Stardust spacecraft shows a wide diversity ("Evidence for interstellar origin of seven dust particles collected by the Stardust spacecraft").

|

|

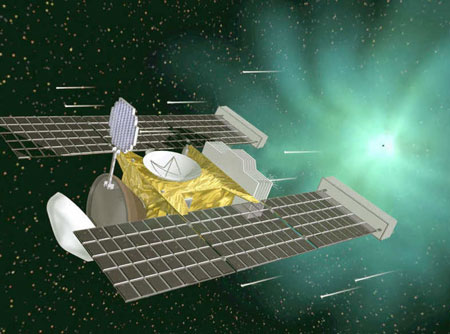

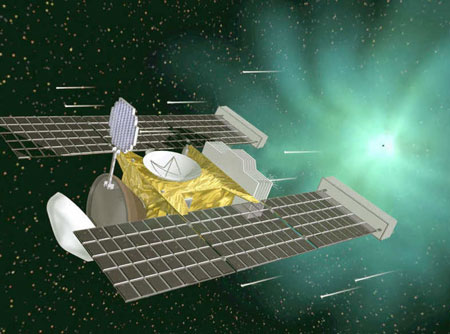

2006 was an important year for the exploration of our solar system: NASA’s Stardust spacecraft brought back to Earth cometary dust as well as smallest amounts of material from the enormous space between the stars, the interstellar space. This material is of scientific significance for various reasons: it refracts the light of stars and allows for conclusions about the size of the universe. It also provides the raw material for the formation of stars and planets and serves as a catalyst for the formation of molecules. In the current issue of the science magazine ‘Science’, an international team from 33 research institutes presents, for the first time, the structure and chemical composition of interstellar dust particles, which were collected by the Stardust space craft.

|

|

| Stardust on the way through the universe: The unfolded "dust catcher“ of the spacecraft is clearly visible in this illustration. (Image: NASA/JPL)

|

|

The researchers identified seven particles with a total mass of a few picograms. One picogram is the equivalent of one trillionth of a gram. Even if the number of particles and mass seems very low, the extraterrestrial material is scientific unchartered territory for Peter Hoppe from the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry. ‘This is the first time that we were able to examine contemporary interstellar dust on Earth,’ says the researcher from Mainz. Previously, the extraterrestrial material could only be analyzed by means of spectroscopic observations. ‘We have found that the size, elemental composition and the structure of the particles differ to a great extent. We did not expect that.’ The term contemporary is relative for astrophysicists such as Hoppe, as the average lifetime of dust particles in interstellar space is around 500 million years; compared to our 4.6 billion year-old solar system this is quite a short period.

|

|

Contrary to predictions, two dust particles were found to be crystalline and not amorphous, i.e. without an ordered structure of atoms. ‘We had expected a crystalline structure in maximum two percent of the dust,’ says Jan Leitner, a member of Peter Hoppe’s team. According to previous theories, the majority of crystalline particles in interstellar space is destroyed by high-energy cosmic rays and shock waves or converted into amorphous dust.

|

|

For the collection of dust particles, the spacecraft was equipped with a special particle collector: On the top of the spacecraft, a tennis racket-sized round grid would protrude into space and catch dust particles on its surface.

|

|

Aluminum foil was wrapped around the walls of these sample tray frames. A specially developed aerogel was packed in the aluminum grid, which slowed down the particles on impact, keeping their structure intact.

|

|

The Stardust mission, which ran a total of six years, was divided into two phases for the collection of cometary dust and interstellar dust. First, the spacecraft collected interstellar dust at the front of the collector, for a period of 195 days. NASA turned the collector by 180 degrees for the subsequent flight through the tail of comet Wild 2, so that the cometary particles landed on the reverse side.

|

|

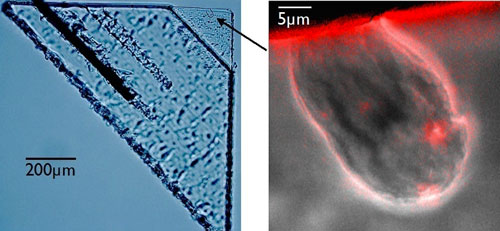

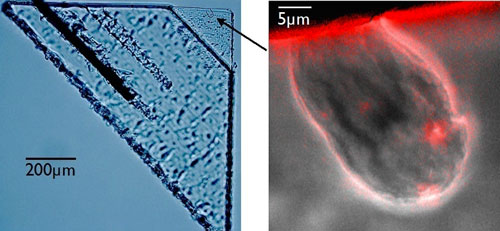

| Cosmic searching for traces: The arrow points to a particle that was captured by the spacecraft, Stardust (left). Next to it, a magnified picture of the impact spot. (Image: Westphal et al. 2014, Science/AAAS)

|

|

Back on Earth, spotting the dust particles presented a seemingly impossible task for scientists, as the dust collectors needed to be scanned micron by micron for impact. This would be the equivalent of an analysis of more than 1.5 million photos of the aerogel. Researchers then approached the public in an unprecedented mission and uploaded the photographs to a website. Thousands of volunteers joined ‘Stardust@home’ and analyzed the images, following a detailed instruction, in order to find the sought-after dust. On the overall, the volunteers made three finds - a great success, which the 66 researchers expressed by naming the ‘30,714 Stardust@home dusters’ in the list of authors of the current issue of Science. Altogether, up to now, four dust particles where found on the aluminum foil and three in the aerogel.

|

|

Peter Hoppe’s team concentrated on the foil. The Mainz team had received a 90 square millimeter piece from NASA. “Searching the foil was a true labor of Sisyphus, as we analyzed approximately 50,000 images. As the dust craters are smaller than a thousandth of a millimeter, we scanned the foil, piece by piece, using an electron microscope,” the researcher Jan Leitner remembers.

|

|

The team found five particles. However, four of the craters only contained abrasion material from the solar cells of the spacecraft. One sample, however, was in fact extraterrestrial and received the unspectacular name I1044N,3. Chemical analysis revealed that this was a ferromagnesian silicate. Other samples contained iron sulfide and elemental iron in addition to aluminum, chromium, manganese, nickel and calcium. As it was not possible to prove the presence of these forms of iron by spectroscopic investigations from Earth, this was another success of two years of working for the researcher community.

|

|

Although only a small portion of the surface of the Stardust collector has been scanned, for the time being, the analysis of the interstellar dust is completed for Peter Hoppe and his team. The remaining samples are now available to scientists around the world for identification and analysis of further particles. Perhaps, these studies will provide some new surprises.

|