| Jan 19, 2015 |

Cosmic radio burst caught red-handed

|

|

(Nanowerk News) Swinburne University of Technology PhD student, Emily Petroff, 'saw' the burst live - a first for astronomers.

|

|

Lasting only milliseconds, the first such radio burst was discovered in 2007 by astronomers combing old Parkes data archives for unrelated objects.

|

|

Six more bursts, apparently from outside our Galaxy, have now been found with the Parkes telescope and a seventh with the Arecibo telescope in Puerto Rico.

|

|

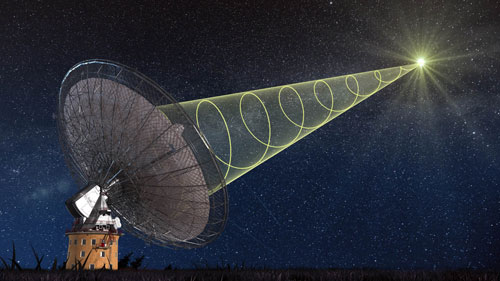

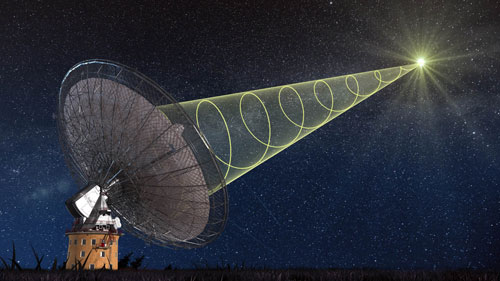

| A schematic illustration of CSIRO’s Parkes radio telescope receiving the polarised signal from the new ‘fast radio burst’. (Image: Swinburne Astronomy Productions)

|

|

Astronomers worldwide have been vying to explain the phenomenon.

|

|

"These bursts were generally discovered weeks, months or even more than a decade after they happened," Ms Petroff said.

|

|

"We are the first to catch one in real time."

|

|

Confident that she would spot a 'live' burst, Ms Petroff had an international team of astronomers poised to make rapid follow-up observations, at wavelengths from radio to X-ray.

|

|

After the Parkes telescope saw the burst go off, the team swung into action on twelve telescopes around the world – in Australia, California, the Canary Islands, Chile, Germany, Hawaii, and India – as well as spaced based telescopes.

|

|

"We can rule out some ideas because no counterparts were seen in the optical, infrared, ultraviolet or X-ray," CSIRO’s Head of Astrophysics, Dr Simon Johnston said.

|

|

"However, the neat idea that we are seeing a neutron star imploding into a black hole remains a possibility."

|

|

One of the big unknowns of fast radio bursts is their distance. The characteristics of the radio signal – how it is 'smeared out' in frequency from travelling through space – indicate that the source of the new burst was up to 5.5 billion light-years away.

|

|

"This means it could have given off as much energy in a few milliseconds as the Sun does in a day," Ms Petroff said.

|

|

She said identifying the origin of the fast radio bursts is now only a matter of time.

|

|

"We've set the trap. Now we just have to wait for another burst to fall into it."

|

|

The finding is published today in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society ("A real-time fast radio burst: polarization detection and multiwavelength follow-up").

|