| Posted: Dec 08, 2008 | |

Nanotechnology appears to fail the moral litmus test of religion |

|

| (Nanowerk Spotlight) When it comes to nanotechnologies, Americans have a big problem: Nanotechnology and its capacity to alter the fundamentals of nature, it seems, are failing the moral litmus test of religion. | |

| In a report published in the journal Nature Nanotechnology, survey results from the United States and Europe reveal a sharp contrast in the perception that nanotechnology is morally acceptable ("Religious beliefs and public attitudes toward nanotechnology in Europe and the United States"). Those views, according to the report, correlate directly with aggregate levels of religious views in each country surveyed. | |

| In the United States and a few European countries where religion plays a larger role in everyday life, notably Italy, Austria and Ireland, nanotechnology and its potential to alter living organisms or even inspire synthetic life is perceived as less morally acceptable. In more secular European societies, such as those in France and Germany, individuals are much less likely to view nanotechnology through the prism of religion and find it ethically suspect. | |

|

|

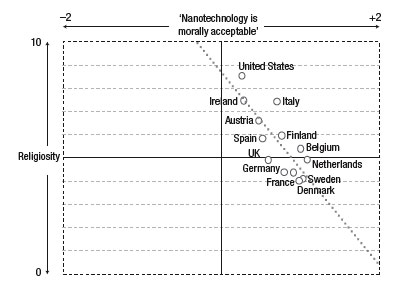

| Relationship between strength of religious beliefs and moral acceptance of nanotechnology. Based on country-level data, we see a negative relationship between levels of religiosity (vertical axis) and beliefs that nanotechnology is morally acceptable (horizontal axis). More religious countries cluster together at the top end of the dotted regression line, and more secular countries at the bottom end. The average responses plotted here somewhat under-represent the range of responses across all response categories. The proportion of respondents who disagreed (that is, -1 or -2) that nanotechnology was morally acceptable was highest in the United States (24.9%) and lowest in Italy (7.3%). The percentages for respondents who agreed (that is, +1 or +2) was highest in Belgium (82.4%) and lowest in Ireland (33.5%). (Reprinted with permission from Nature Publishing Group) | |

| “The level of ‘religiosity’ in a particular country is one of the strongest predictors of whether or not people see nanotechnology as morally acceptable,” says Dietram Scheufele, a University of Wisconsin-Madison professor of life sciences communication and the lead author of the new study. “Religion was the strongest influence over everything.” | |

| Scheufele says that, as with many other political and scientific issues, citizens rely on cognitive shortcuts or heuristics to make sense of issues for which they have low levels of knowledge. "These heuristics can include predispositional factors, such as ideological beliefs or value systems, and also short-term frames of reference provided by the media or other sources of information. Recent research suggests that ‘religious filters’ are an important heuristic for scientific issues in general, and nanotechnology in particular. A religious filter is more than a simple correlation between religiosity and attitudes toward science: it refers to a link between benefit perceptions and attitudes that varies depending on respondents’ levels of religiosity. In surveys, seeing the benefits of nanotechnology is consistently linked to more positive attitudes about nanotechnology among less religious respondents, with this effect being significantly weaker for more religious respondents." | |

| The study compared answers to identical questions posed by the 2006 Eurobarometer public opinion survey and a 2007 poll by the University of Wisconsin Survey Center conducted under the auspices of the National Science Foundation-funded Center for Nanotechnology and Society at Arizona State University. The survey was led by Scheufele and Elizabeth Corley, an associate professor in the School of Public Affairs at Arizona State University. | |

| The survey findings, says Scheufele, are important not only because they reveal the paradox of citizens of one of the world’s elite technological societies taking a dim view of the implications of a particular technology, but also because they begin to expose broader negative public attitudes toward science when people filter their views through religion. | |

| “What we captured is nano specific, but it is also representative of a larger attitude toward science and technology,” Scheufele says. “It raises a big question: What’s really going on in our public discourse where science and religion often clash?” | |

| For the United States, the findings are particularly surprising, Scheufele notes, as the country is without question a highly technological society and many of the discoveries that underpin nanotechnology emanated from American universities and companies. The technology is also becoming more pervasive, with more than 1,000 products ranging from more efficient solar panels and scratch-resistant automobile paint to souped-up golf clubs already on the market. | |

| To be sure that religion was such a dominant influence on perceptions of nanotechnology, the group controlled for such things as science literacy, educational performance, and levels of research productivity and funding directed to science and technology by different countries. | |

| “We really tried to control for country-specific factors,” Scheufele explains. “But we found that religion is still one of the strongest predictors of whether or not nanotechnology is morally acceptable and whether or not it is perceived to be useful for society.” | |

| The findings from the 2007 U.S. survey, adds Scheufele, also suggest that in the United States the public’s knowledge of nanotechnology has been static since a similar 2004 survey. Scheufele points to a paucity of news media interest and the notion that people who already hold strong views on the technology are not necessarily seeking factual information about it. | |

| “There is absolutely no change in what people know about nanotechnology between 2004 and 2007. This is partly due to the fact that mainstream media are only now beginning to pay closer attention to the issue. There has been a lot of elite discussion in Washington, D.C., but not a lot of public discussion. And nanotechnology has not had that catalytic moment, that key event that draws public attention to the issue.” | |

|

Become a Spotlight guest author! Join our large and growing group of guest contributors. Have you just published a scientific paper or have other exciting developments to share with the nanotechnology community? Here is how to publish on nanowerk.com. |

|