| Jul 18, 2014 |

It's go time for LUX-Zeplin dark matter experiment

|

|

(Nanowerk News) From the physics labs at Yale University to the bottom of a played-out gold mine in South Dakota, a new generation of dark matter experiments is ready to commence.

|

|

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science and the National Science Foundation recently gave the go-ahead to LUX-Zeplin (LZ), a key experiment in the hunt for dark matter, the invisible substance that may make up much of the universe. Daniel McKinsey, a professor of physics, leads a contingent of Yale scientists working on the project.

|

|

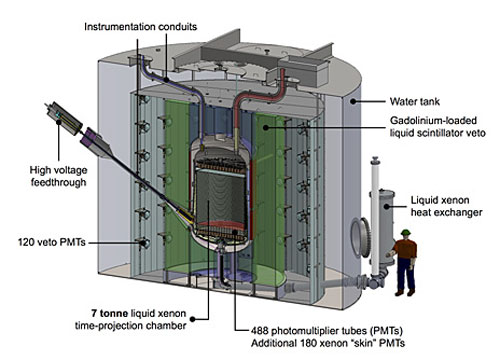

| The LZ water shield, currently housing the LUX experiment.

|

|

"We emerged from a very intense competition," said McKinsey, whose ongoing LUX (Large Underground Xenon) experiment looks for dark matter with a liquid xenon detector placed 4,850 feet below the Earth's surface. The device resides at the Sanford Underground Research Facility, in South Dakota's Black Hills.

|

|

The new, LZ device will boost the size and effectiveness of the original LUX technology.

|

|

"We have the most sensitive detector in the world, with LUX," McKinsey said. "LZ will be hundreds of times more sensitive. It's gratifying to see that our approach is being validated."

|

|

LZ is an international effort, involving scientists from 29 institutions in the United States, Portugal, Russia, and the United Kingdom. The DOE's Lawrence Berkeley National Lab manages the experiment.

|

|

Dark matter is a scientific placeholder, of sorts. Although it can't be seen or felt, its existence is thought to explain a number of important behaviors of the universe, including the structural integrity of galaxies.

|

|

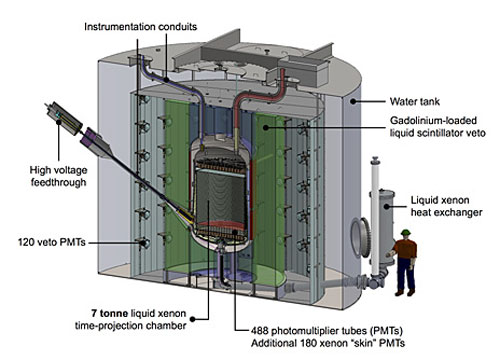

LZ's approach posits that dark matter may be composed of Weakly Interacting Massive Particles – known as WIMPs – which pass through ordinary matter virtually undetected. The experiment aims to spot these particles as they move through a container of dense, liquid xenon. That container will be surrounded by a tank of water, along with an array of sophisticated light sensors and other systems.

|

|

Putting the device down a mineshaft weeds out cosmic rays, McKinsey said. Gamma rays and neutrinos, however, still will be able to seep into the device. They'll be like tiny bowling balls, careening into the liquid xenon and colliding with electrons. Those collisions will be identified and factored out.

|

|

| A 3D rendering of the LZ detector.

|

|

The researchers hope that the remaining collisions, the ones involving nuclei, will identify the presence of dark matter. "It comes down to distinguishing between electron and nuclear recoils," McKinsey said.

|

|

LZ will be a meter taller and significantly wider than its predecessor. The amount of xenon will jump from 250 kilograms to 7,000 kilograms. Such considerations become critical when you're conducting research in a mine, according to McKinsey.

|

|

"Everything has to come down in the same cage," he said.

|

|

As with LUX, a number of systems and components for LZ will be designed and built at Yale. For example, McKinsey said, team members in New Haven will work on calibration systems. They also will construct a system for bringing high voltage into the device's lower grid.

|

|

The goal is to have LZ operational in 2017, while continuing work with the LUX experiment.

|

|

"We want to get moving soon," McKinsey said. "We have new systems we want to start testing. Our activity has begun."

|

|

Two other dark matter initiatives also earned support. Those are the SuperCDMS-SNOLAB, which will look for WIMPs, and ADMX-Gen2, which will search for axion particles.

|