| Aug 28, 2014 |

Uncloaking the King of the Milky Way: The largest star in our home galaxy's largest stellar nursery

|

|

(Nanowerk News) Astronomers led by Shiwei Wu of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy have identified the most massive star in our home galaxy's largest stellar nursery, the star-forming region W49 ("The discovery of a very massive star in W49"). The star, named W49nr1, has a mass between 100 and 180 times the mass of the Sun. Only a few dozen of these very massive stars have been identified so far. As seen from Earth, W49 is obscured by dense clouds of dust, and the astronomers had to rely on near-infrared images from ESO's New Technology Telescope and the Large Binocular Telescope to obtain suitable data. The discovery is hoped to shed light on the formation of massive stars, and on the role they play in the biggest star clusters.

|

|

The discovery of a new, very massive star is exciting to astronomers for more than one reason: Very massive stars, more than 100 times the mass of our own Sun, are something of an astronomical mystery. They are very short-lived (a few million years compared to the 10 billion years of stars like our Sun), which is one reason they are so rare. Among the billions of stars catalogued and examined by astronomers, these very massive specimens amount to no more than a few dozen, most of them discovered over the past few years.

|

|

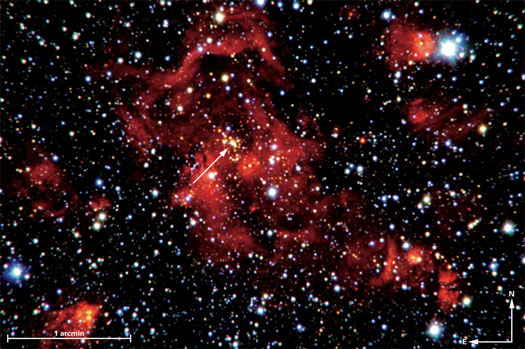

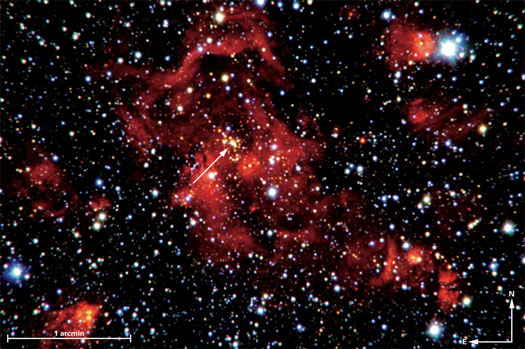

| A colour image of the central area of W49. The massive star W49nr1 is indicated with a white arrow. Please note: the also indicated scale of one arcmin corresponds to only 1/30 of the apparent size of the Full Moon. The colour composite was made by combining images taken with three special filters at different near infrared wavelengths (J, H, bracket gamma).

|

|

Though rare, the massive stars have a decisive influence on their surroundings. They are extremely bright, giving off large amounts of highly energetic UV radiation as well as streams of particles (stellar wind). Typically, such a star will create a bubble around itself, ionizing any nearby gas, and pushing more distant gas ever farther away. Some of this pushed-away gas might actually cause distant gas clouds to collapse, triggering the birth of new stars.

|

|

Until a few years ago, there was even doubt whether such stars could form at all. Theorists have only quite recently managed to simulate the genesis of these massive bodies, and there are now several competing explanations for very massive star formation. In some models, such a star is the result of the merger between two stars forming in an extended star cluster. Up to now, there had only been three clusters (NGC 3603 and the Arches Cluster in our galaxy, R136 in the Large Magellanic Cloud) where such massive stars had actually been found.

|

|

Now, a team of astronomers lead by Shiwei Wu from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy (MPIA) has discovered such a massive star, and not in any location, but in the largest star-forming region known in our Milky Way galaxy, which is called W49. The discovery was a challenging task: W49 is located at a distance of 36,000 light-years (11.1 kpc), almost half-way across our home galaxy, cloaked by the dust of two spiral arms that lie between us and the cluster.

|

|

Shiwei Wu explains: „Because W49 is hidden behind huge regions of interstellar dust, only one trillionth of the visible light it sends in our direction actually reaches Earth. That’s why we observed the cluster’s infrared light, which can pass through dust almost unhindered.”

|

|

Using a spectrum obtained with the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in the infrared, the astronomers could determine the star’s type (“O2-3.5If* star”) and use this information and the star’s measured brightness to estimate its temperature and total light emission. Comparison with models for stellar evolution give an estimate of the star’s mass between 100 and 180 solar masses.

|

|

Because of the cluster’s size, W49 is one of the most important sites within our galaxy for studying the formation and evolution of very massive stars – and with W49nr1, the astronomers have now identified the cluster’s key object. With this and future observations, they have hopes of settling one of astronomy’s weightiest open questions: the birth of our galaxy’s most massive stars.

|