| Posted: Feb 27, 2015 |

Cheaper, more durable nanocarbon catalyst for fuel cell used in cars, at data centers

|

|

(Nanowerk News) For nearly half a century, scientists have been trying to replace precious metal catalysts in fuel cells. Now, for the first time, researchers at Case Western Reserve University have shown that an inexpensive metal-free catalyst performs as well as costly metal catalysts at speeding the oxygen reduction reaction in an acidic fuel cell.

|

|

The carbon-based catalyst also corrodes less than metal-based materials and has proved more durable.

|

|

The findings are major steps toward making low-cost catalysts commercially available, which could, in turn, reduce the cost to generate clean energy from PEM fuel cells--the most common cell being tested and used in cars and stationary power plants. The study will be published online in the journal Science Advances onFeb. 27.

|

|

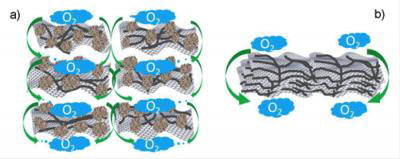

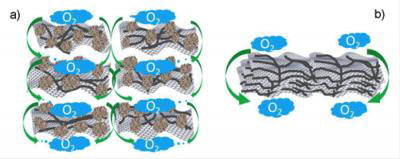

| Structure enables a carbon-based catalyst to perform comparably with metal catalysts in an acidic fuel cell. A: Carbon black agglomerates maintain a clear distance between graphene sheets imbedded with carbon nanotubes, allowing oxygen and electrolyte to flow through and speeding the oxygen-reduction reaction. B: Without the agglomerates, the sheets stack closely, stalling the reaction. (Image: Liming Dai)

|

|

"This definitely should move the field forward," said Liming Dai, the Kent Hale Smith Professor of macromolecular science and engineering at Case Western Reserve and senior author of the research. "It's a major breakthrough for commercialization."

|

|

Dai worked with lead investigator Jianglan Shui, who was a CWRU postdoctoral researcher and is now a materials science and engineering professor at Beihang University, Beijing; PhD student Min Wang, who did some of the testing; and postdoctoral researcher Fen Du, who made the materials. The effort builds on the Dai lab's earlier work developing carbon-based catalysts that significantly outperformed platinum in an alkaline fuel cell.

|

|

The group pursued a non-metal catalyst to perform in acid because the standard bearer among fuel cells, the PEM cell, uses an acidic electrolyte. PEM stands for both proton exchange membrane and polymer electrolyte membrane, which are interchangeable names for this type of cell.

|

|

The key to the new catalyst is its rationally-designed porous structure, Dai said. The researchers mixed sheets of nitrogen-doped graphene, a single-atom thick, with carbon nanotubes and carbon black particles in a solution, then freeze-dried them into composite sheets and hardened them.

|

|

Graphene provides enormous surface area to speed chemical reactions, nanotubes enhance conductivity, and carbon black separates the graphene sheets for free flow of the electrolyte and oxygen, which greatly increased performance and efficiency. The researchers found that those advantages were lost when they allowed composite sheets to arrange themselves in tight stacks with little room between layers.

|

|

A fuel cell converts chemical energy into electrical energy by removing electrons from a fuel, such as hydrogen, at the cell's anode, or positive electrode. This creates a current.

|

|

Hydrogen ions produced are carried by the electrolyte through a membrane to the cathode, or negative electrode, where the oxygen reduction reaction takes place. Oxygen molecules are split and reduced by the addition of electrons and combine with the hydrogen ions to form water and heat--the only byproducts.

|

|

Testing showed the porous catalyst performs better and is more durable than the state-of-the-art nonprecious iron-based catalyst. Dai's lab continues to fine-tune the materials and structure as well as investigate the use of non-metal catalysts in more areas of clean energy.

|