| Posted: Jun 26, 2015 |

High-performance microscope displays pores in the cell nucleus with greater precision

|

|

(Nanowerk News) An active exchange takes place between the cell nucleus and the cytoplasm: Molecules are transported into the nucleus or from the nucleus into the cytoplasm. In a human cell, more than a million molecules are transported into the cell nucleus every minute. In the process, special pores embedded in the nucleus membrane act as transport gates. These nuclear pores are among the largest and most complex structures in the cell and comprise more than 200 individual proteins, which are arranged in a ring-like architecture. They contain a transportation channel, through which small molecules can pass unobstructed, while large molecules have to meet certain criteria to be transported.

|

|

Now, for the first time, an University of Zurich research team headed by Professor Ohad Medalia has succeeded in displaying the spatial structure of the transport channel in the nuclear pores in high resolution (Nature Communications, "Structure and Gating of the Nuclear Pore Complex").

|

|

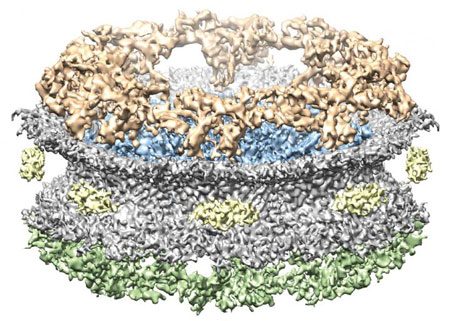

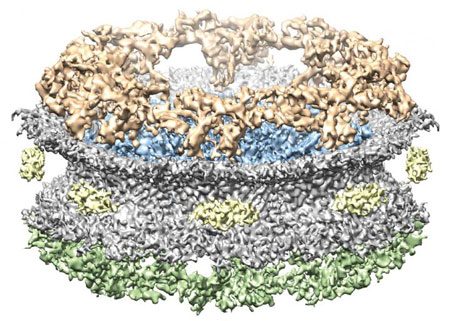

| The nuclear pore complex is comprised of several layered rings: the cytoplasmic ring (gold), the spoke ring within the pore (blue) and the nucleoplasmic ring (green). (Image: University of Zurich) (click on image to enlarge)

|

|

"Molecular gate" discovered in the pore channel

|

|

For their study, the scientists used shock-frozen specimens of clawed frog oocytes. With the aid of cryo-electron microscopes, Medalia's team was able to display the miniscule nuclear pores, which were merely a ten thousandth of a millimeter in diameter, at a considerably higher resolution than ever before. As a result, they uncovered new details: "We discovered a previously unobserved structure inside the nuclear pore that forms a kind of molecular gate, which can only be opened by molecules that hold the right key," explains Medalia. This "molecular gate" is the so-called spoke ring, which is sandwiched between two other rings and extends inside the nuclear pores. The gate itself consists of a fine lattice, which enables small molecules to slip through unobstructed.

|

|

The new, high-resolution presentation of the nuclear pore structure leads to a better understanding of why certain molecules are allowed to pass through the nuclear pores while others are turned away. It also helps improve our understanding of the development of some diseases that involve a defective transportation to the nuclear pores - such as intestinal, ovarian and thyroid cancer.

|