| Posted: Jan 08, 2016 |

Atomic moves revealed by ultrabright electron pulses

(Nanowerk News) Current ways of looking at the structure of molecules produce blurred images, which may show the average locations of atoms, but hide any changes that happen faster than the instruments can probe. Understanding not only the average structure of molecules, but also how they move and change in response to light, is particularly important for developing new electronic, magnetic and photo-functional materials.

|

|

Moving from simple to complex systems

|

|

An international team of researchers from Tokyo Institute of Technology, Ehime University, RIKEN, the Max Planck Institute for the Structure and Dynamics of Matter, and the University of Toronto used an ultrabright and ultrashort electron source to study the crystal structure of a platinum compound that comes from a family of materials with the ability to switch between insulating, metallic and superconducting states (Science, "Direct observation of collective modes coupled to molecular-orbital driven charge transfer").

|

|

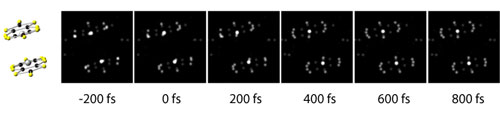

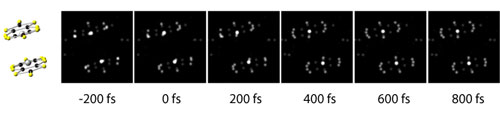

| These frames of the molecular movie show how the relative positions and shapes of Pt(dmit)2 molecules change in the phase transitions material Me4P[Pt(dmit)2]2, as it is triggered by laser light (fs: femtosecond). (click on image to enlarge)

|

|

This is the first time this emerging technique has been used for such a complicated crystal structure. The analysis was simplified by combining the results with those from different techniques, to produce a clear image of the crystal, and show how it changes after interacting with light.

|

|

Watching atoms move

|

|

The team established that light pulses change the molecular structure in the same way as a phase change of the material. They also revealed several new and unexpected structural changes. With this new approach, they probed the details of molecular motions, and the response of electrons to light, showing how changes in the electronic, molecular, and lattice structures act together to cause ultrafast changes in the crystal structure.

|

|

The broad implication of this work is that this ultrafast electron technique can now be used in much more complicated systems. Such insight into molecular behavior on these short time scales will undoubtably enrich our understanding of how materials respond to light and paves the way to new functional materials.

|