| Posted: Apr 18, 2016 |

What screens are made of: New twists (and bends) in LCD research

(Nanowerk News) Liquid crystals, discovered more than 125 years ago, are at work behind the screens of TV and computer monitors, clocks, watches and most other electronics displays, and scientists are still discovering new twists--and bends--in their molecular makeup.

|

|

Liquid crystals are an exotic state of matter that flows like a fluid but in which the molecules may be oriented in a crystal-like way. At the microscopic scale, liquid crystals come in several different configurations, including a naturally spiraling "twist-bend" molecular arrangement, discovered in 2013, that has excited a flurry of new research.

|

|

Now, using a pioneering X-ray technique developed at the U.S. Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab), a research team has recorded the first direct measurements confirming a tightly wound spiral molecular arrangement that could help unravel the mysteries of its formation and possibly improve liquid-crystal display (LCD) performance, such as the speed at which they selectively switch light on or off in tiny screen areas.

|

|

The findings could also help explain how so-called "chiral" structure--molecules can exhibit wildly different properties based on their left- or right-handedness (chirality), which is of interest in biology, materials science and chemistry--can form from organic molecules that do not exhibit such handedness.

|

|

"This newly discovered 'twist-bend' phase of liquid crystals is one of the hottest topics in liquid crystal research," said Chenhui Zhu, a research scientist at Berkeley Lab's Advanced Light Source (ALS), where the X-ray studies were performed.

|

|

"Now, we have provided the first definitive evidence for the twist-bend structure. The determination of this structure will without question advance our understanding of its properties, such as its response to temperature and to stress, which may help improve how we operate the current generation of LCDs."

|

|

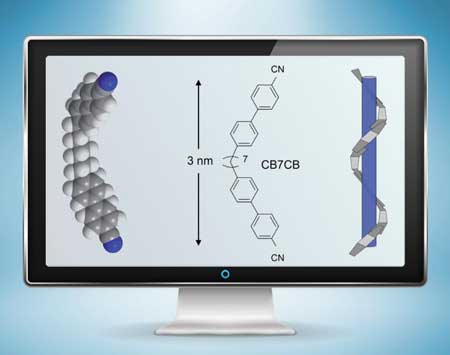

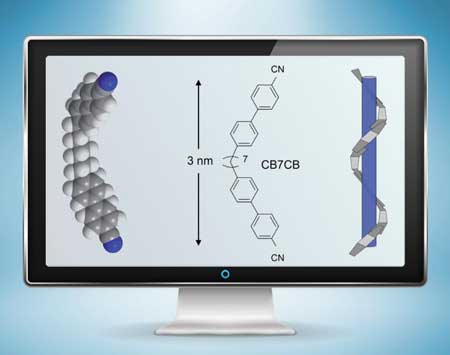

| Researchers examined the spiral 'twist-bend' structure (right) formed by boomerang-shaped liquid crystal molecules (left and center) measuring 3 nanometers in length, using a pioneering X-ray technique at Berkeley Lab's Advanced Light Source. A better understanding of this spiral form, discovered in 2013, could lead to new applications for liquid crystals and improved liquid-crystal display screens. (Image: Zosia Rostomian/Berkeley Lab)

|

|

Zhu was the lead author on a related research paper published in the April 7 edition of Physical Review Letters ("Resonant Carbon K-Edge Soft X-Ray Scattering from Lattice-Free Heliconical Molecular Ordering: Soft Dilative Elasticity of the Twist-Bend Liquid Crystal Phase").

|

|

While there are now several competing screen technologies to standard LCDs, the standard LCD market is still huge, representing more than one-third of the revenue in the electronic display market. The overall display market is expected to top $150 billion in revenue this year.

|

|

The individual molecules in the structure determined at Berkeley Lab are constructed like flexible, nanoscale boomerangs, just a few nanometers, or billionths of a meter, in length and with rigid ends and flexible middles. In the twist-bend phase, the spiraling structure they form resembles a bunch of snakes lined up and then wound snugly around the length of an invisible pole.

|

|

Zhu tuned low-energy or "soft" X-rays at the ALS to examine carbon atoms in the liquid crystal molecules, which provided details about the molecular orientation of their chemical bonds and the structure they formed. The technique he used for the study is known as soft X-ray scattering. The spiraling, helical molecular arrangement of the liquid crystal samples would have been undetectable by conventional X-ray scattering techniques.

|

|

The measurements show that the liquid crystals complete a 360-degree twist-bend over a distance of just 8 nanometers at room temperature, which Zhu said is an "amazingly short" distance given that each molecule is 3 nanometers long, and such a strongly coiled structure is very rare.

|

|

The driving force for the formation of the tight spiral in the twist-bend arrangement is still unclear, and the structure exhibits unusual optical properties that also warrant further study, Zhu said.

|

|

Researchers found that the spiral "pitch," or width of one complete spiral turn, becomes a little longer with increasing temperature, and the spiral abruptly disappears at sufficiently high temperature as the material adopts a different configuration.

|

|

"Currently, this experiment can't be done anywhere else," Zhu said. "We are the first team to use this soft X-ray scattering technique to study this liquid-crystal phase."

|

|

Standard LCDs often use nematic liquid crystals, a phase of liquid crystals that naturally align in the same direction--like a group of compass needles that are parallel to one another, pointing in one direction.

|

|

In these standard LCD devices, rod-like liquid crystal molecules are sandwiched between specially treated plates of glass that cause the molecules to "lie down" rather than point toward the glass. The glass is typically treated to induce a 90-degree twist in the molecular arrangement, so that the molecules closest to one glass plate are perpendicular to those closest to the other glass plate.

|

|

It's like a series of compass needles made to face north at the top, smoothly reorienting to the northeast in the middle, and pointing east at the bottom. This molecularly twisted state is then electrically distorted to allow polarized light to pass through at varying brightness, for example, or to block light (by straightening the twist completely).

|

|

Future experiments will explore how the spirals depend on molecular shape and respond to variations in temperature, electric field, ultraviolet light, and stress, Zhu added.

|

|

He also hopes to explore similar spiraling structures, such as a liquid crystal phase known as the helical nanofilament, which shows promise for solar energy applications. Studies of DNA, synthetic proteins, and amyloid fibrils such as those associated with Alzheimer's disease, might help explain the role of handedness in how organic molecules self-assemble.

|

|

With brighter, more laser-like X-ray sources and faster X-ray detectors, it may be possible to see details in how the spiraling twist-bend structure forms and fluctuates in real time in materials, Zhu also said.

|

|

"I am hoping our ongoing experiments can provide unique information to benefit other theories and experiments in this field," he noted.

|