| Posted: May 22, 2018 |

Tunable diamond string may hold key to quantum memory

(Nanowerk News) A quantum internet promises completely secure communication. But using quantum bits or qubits to carry information requires a radically new piece of hardware – a quantum memory. This atomic-scale device needs to store quantum information and convert it into light to transmit across the network.

|

|

A major challenge to this vision is that qubits are extremely sensitive to their environment, even the vibrations of nearby atoms can disrupt their ability to remember information. So far, researchers have relied on extremely low temperatures to quiet vibrations but, achieving those temperatures for large-scale quantum networks is prohibitively expensive.

|

|

Now, researchers at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) and the University of Cambridge have developed a quantum memory solution that is as simple as tuning a guitar.

|

|

The researchers engineered diamond strings that can be tuned to quiet a qubit’s environment and improve memory from tens to several hundred nanoseconds, enough time to do many operations on a quantum chip.

|

|

“Impurities in diamond have emerged as promising nodes for quantum networks,” said Marko Loncar, the Tiantsai Lin Professor of Electrical Engineering at SEAS and senior author of the research. “However, they are not perfect. Some kinds of impurities are really good at retaining information but have a hard time communicating, while others are really good communicators but suffer from memory loss. In this work, we took the latter kind, and improved the memory by ten times.”

|

|

The research is published in Nature Communications ("Controlling the coherence of a diamond spin qubit through its strain environment").

|

|

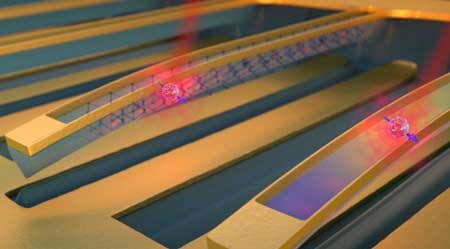

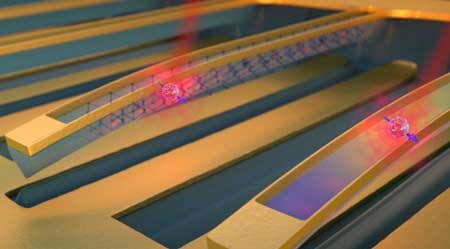

| Electrodes stretch diamond strings to increase the frequency of atomic vibrations to which an electron is sensitive, just like tightening a guitar string increases the frequency or pitch of the string. The tension quiets a qubit’s environment and improves memory from tens to several hundred nanoseconds, enough time to do many operations on a quantum chip. (Image: Second Bay Studios/Harvard SEAS)

|

|

Impurities in diamond, known as silicon-vacancy color centers, are powerful qubits. An electron trapped in the center acts as a memory bit and can emit single photons of red light, which would in turn act as long-distance information carriers of a quantum internet. But with the nearby atoms in the diamond crystal vibrating randomly, the electron in the center quickly forgets any quantum information it is asked to remember.

|

|

“Being an electron in a color center is like trying to study at a loud marketplace,” said Srujan Meesala, a graduate student at SEAS and co-first author of the paper. “There is all this noise around you. If you want to remember anything, you need to either ask the crowds to stay quiet or find a way to focus over the noise. We did the latter.”

|

|

To improve memory in a noisy environment, the researchers carved the diamond crystal housing the color center into a thin string, about one micron wide — a hundred times thinner than a strand of hair — and attached electrodes to either side. By applying a voltage, the diamond string stretches and increases the frequency of vibrations the electron is sensitive to, just like tightening a guitar string increases the frequency or pitch of the string.

|

|

“By creating tension in the string, we increase the energy scale of vibrations that the electron is sensitive to, meaning it can now only feel very high energy vibrations,” said Meesala. “This process effectively turns the surrounding vibrations in the crystal to an irrelevant background hum, allowing the electron inside the vacancy to comfortably hold information for hundreds of nanoseconds, which can be a really long time on the quantum scale. A symphony of these tunable diamond strings could serve as the backbone of a future quantum internet.”

|

|

Next, the researchers hope to extend the memory of the qubits to the millisecond, which would enable hundreds of thousands of operations and long-distance quantum communication.

|