| Posted: Jun 15, 2018 |

Squeezing light at the nanoscale

(Nanowerk News) Researchers at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) have developed a new technique to squeeze infrared light into ultra-confined spaces, generating an intense, nanoscale antenna that could be used to detect single biomolecules.

|

|

The researchers harnessed the power of polaritons, particles that blur the distinction between light and matter. This ultra-confined light can be used to detect very small amounts of matter close to the polaritons. For example, many hazardous substances, such as formaldehyde, have an infrared signature that can be magnified by these antennas. The shape and size of the polaritons can also be tuned, paving the way to smart infrared detectors and biosensors.

|

|

The research is published in Science Advances ("Ultra-confined mid-infrared resonant phonon polaritons in van der Waals nanostructures").

|

|

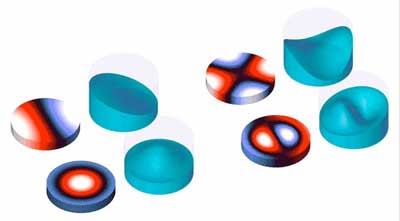

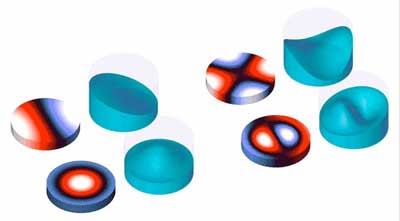

| Nano-discs act as micro-resonators, trapping infrared photons and generating polaritons. When illuminated with infrared light, the discs concentrate light in a volume thousands of times smaller than is possible with standard optical materials. At such high concentrations, the polaritons oscillate like water sloshing in a glass, changing their oscillation depending on the frequency of the incident light. (Image: Harvard SEAS)

|

|

"This work opens up a new frontier in nanophotonics," said Federico Capasso, the Robert L. Wallace Professor of Applied Physics and Vinton Hayes Senior Research Fellow in Electrical Engineering, and senior author of the study. "By coupling light to atomic vibrations, we have concentrated light into nanodevices much smaller than its wavelength, giving us a new tool to detect and manipulate molecules."

|

|

Polaritons are hybrid quantum mechanical particles, made up of a photon strongly coupled to vibrating atoms in a two-dimensional crystal.

|

|

"Our goal was to harness this strong interaction between light and matter and engineer polaritons to focus light in very small spaces," said Michele Tamagnone, postdoctoral fellow in Applied Physics at SEAS and co-first author of the paper.

|

|

The researchers built nano-discs -- the smallest about 50 nanometers high and 200 nanometers wide -- made of two-dimensional boron nitride crystals. These materials act as micro-resonators, trapping infrared photons and generating polaritons. When illuminated with infrared light, the discs were able to concentrate light in a volume thousands of times smaller than is possible with standard optical materials, such as glass.

|

|

At such high concentrations, the researchers noticed something curious about the behavior of the polaritons: they oscillated like water sloshing in a glass, changing their oscillation depending on the frequency of the incident light.

|

|

"If you tip a cup back-and-forth, the water in the glass oscillates in one direction. If you swirl your cup, the water inside the glass oscillates in another direction. The polaritons oscillate in a similar way, as if the nano-discs are to light what a cup is to water," said Tamagnone.

|

|

Unlike traditional optical materials, these boron nitride crystals are not limited in size by the wavelength of light, meaning there is no limit to how small the cup can be. These materials also have tiny optical losses, meaning that light confined to the disc can oscillate for a long time before it settles, making the light inside even more intense.

|

|

The researchers further concentrated light by placing two discs with matching oscillations next to each other, trapping light in the 50-nanometer gap between them and creating an infrared antenna. As light concentrates in smaller and smaller volumes, its intensity increases, creating optical fields so strong they can exert measurable force on nearby particles.

|

|

"These light-induced forces serve also as one our detection mechanisms," said Antonio Ambrosio, a principal scientist at Harvard's Center for Nanoscale Systems. "We observed this ultra-confined light by the motion it induces on an atomically sharp tip connected to a cantilever."

|

|

A future challenge for the Harvard team is to optimize these light nano-concentrators to achieve intensities high enough to enhance the interaction with a single molecule to detectable values.

|