| Posted: Oct 11, 2018 | |

Microfluidic molecular exchanger helps control therapeutic cell manufacturing(Nanowerk News) Researchers have demonstrated an integrated technique for monitoring specific biomolecules – such as growth factors – that could indicate the health of living cell cultures produced for the burgeoning field of cell-based therapeutics. |

|

| Using microfluidic technology to advance the preparation of samples from the chemically complex bioreactor environment, the researchers have harnessed electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) to provide online monitoring that they believe will provide for therapeutic cell production the kind of precision quality control that has revolutionized other manufacturing processes. | |

| “The way that the production of cell therapeutics is done today is very much an art,” said Andrei Fedorov, Woodruff Professor in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology. “Process control must evolve very quickly to support the therapeutic applications that are emerging from bench science today. We think this technology will help us reach the goal of making these exciting cell-based therapies widely available.” | |

| By measuring very low concentrations of specific compounds secreted or excreted by cells, the technique could also help identify which biomolecules – of widely varying sizes – should be monitored to guide the control of cell health. Ultimately, the researchers hope to integrate their label-free monitoring directly into high-volume bioreactors that will produce cells in quantities large enough to make the new therapies available at a reasonable cost and consistent quality. | |

|

|

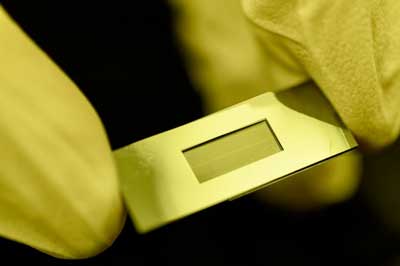

| Close-up image shows the Dynamic Mass Spectrometry Probe developed to monitor the health of living cell cultures. (Image: Rob Felt, Georgia Tech) | |

| Development of the Dynamic Mass Spectrometry Probe (DMSP) was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) Engineering Research Center for Cell Manufacturing Technologies (CMaT), which is headquartered at Georgia Tech. The work was reported in the journal Biotechnology and Bioengineering ("Dynamic Mass Spectrometry Probe (DMSP) for ESI-MS Monitoring of Bioreactors for Therapeutic Cell Manufacturing"). | |

| Traditional ESI-MS techniques have revolutionized analytical chemistry by allowing precise identification of complex biological compounds. Because of complex sample preparation requirements, existing approaches to ESI-MS require too much time to be useful for continuous monitoring of cell growth in bioreactors, where maintaining narrow parameters for specific indicators of cellular health is critical. Biological samples also contain salts, which must be removed before introduction into the ESI-MS system. | |

| To accelerate the analytical process, Fedorov and a team that included graduate research assistant Mason Chilmonczyk and research engineer Peter Kottke used microfluidic technology to help separate compounds of interest from the salts. Salt removal uses a monolithic device in which a size-selective membrane with nanoscale pores is placed between two fluid flows, one the chemically complex sample drawn from the bioreactors and the other salt-free water with conditioning compounds. | |

| The smaller salt molecules readily diffuse out of the sampled bioreactor flow through the nanopores, while the larger biomolecules mostly remain for the subsequent ESI-MS analysis. Meanwhile, chemical additives are at the same time introduced into the sample mixture through the same membrane nanopores to enhance ionization of the target biomolecules in the sampled mixture for improved ESI-MS analysis. | |

| “We have used advanced microfabrication techniques to create a microfluidic device that will be able to treat samples in less than a minute,” said Chilmonczyk. “Traditional sample preparation can require hours to days.” | |

| The process can currently remove as much as 99 percent of the salt, while retaining 80 percent of the biomolecules. Introduction of the conditioning chemicals allows the molecules to accept a greater charge, improving the capability of the mass spectrometer to detect low concentration biomolecules, and to measure large molecules. | |

| “We can detect really high molecular weight molecules that the mass spectrometer normally wouldn’t be able to detect,” Fedorov said. “The size difference in the molecules of interest can be dramatic, so the improvement in the limit of detection across a broad range of analyte molecular weights will allow this technique to be more useful in cell manufacturing.” | |

| Because they use state of the art microfabrication techniques, the DMSP devices can be mass produced, allowing sampling to be scaled up to include multiple bioreactors at low cost. The small size of the device channels – which are just five microns tall – allows the system to produce results with samples as small as 20 nanoliters – with the potential for reducing that to as little as a single nanoliter. | |

| “We need to monitor small concentrations of large biomolecules in this messy environment in a production line in such a way that we can check at any point how the cells are doing,” Fedorov said. “This system could continuously monitor whether certain molecules are excreted or secreted at a reduced or increased rate. By correlating these measurements with cell health and potency, we could improve the manufacturing process.” | |

| Before the analytical techniques can be applied to quality control, the researchers must first identify biomolecules that indicate health of the growing cells. By sampling the bioreactor content locally in the immediate vicinity of cells and allowing identification of very small quantities of biochemicals, the DMSP technology can help researchers identify changes in molecular concentrations – which range from pico-molar to micro-molar – that may indicate the state of cells in the bioreactors. This would prompt adjustment of conditions in a bioreactor just in time to return to the state of healthy cell growth. | |

| “In this situation, we often can’t see the trees for the forest,” said Fedorov. “There is a lot of material available, but we are looking for just a handful of individual trees that indicate the health of the cells. Because the forest is overgrown, the few selected trees we need to examine are hard to find. This is a grand challenge technologically.” |

| Source: By John Toon, Georgia Institute of Technology | |

|

Subscribe to a free copy of one of our daily Nanowerk Newsletter Email Digests with a compilation of all of the day's news. |