| Dec 07, 2018 | |

An embellished coat for bone implants(Nanowerk News) Only when the human cells connect with the implant allowing the formation of a fibrous tissue between the bone and the biomaterial, will patients be able to benefit from a long-lasting and successful bone implantation. |

|

| Scientists from the European project Laser4Surf are currently developing a multi-beam optical module to treat the metallic surfaces of dental implants to achieve the best cell adhesion and antibacterial properties. | |

| “Surface treatment allows either a bigger surface in contact between the implant and the bone or a better affinity regarding the chemical interaction between the cell and the implant,” explains Marilys Blanchy, a research & development manager at Rescoll, one of the project’s partners. Rescoll is a technology centre, specialised in polymer science, adhesive coating and medical devices, based in Bordeaux, on France's Atlantic Coast. | |

|

|

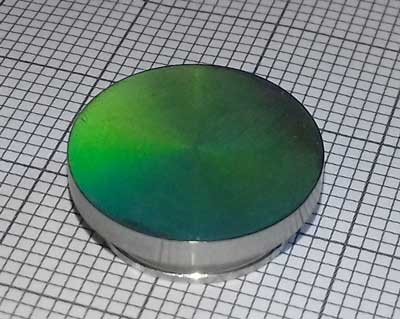

| LIPSS on a titanium surface reflecting the flashlight colorful. (Image: Centro de Estudios e Investigaciones Técnicas de Gipuzkoa (CEIT)) | |

| The materials used so far in the implant dentistry are biocompatible with the body, but inert related to the cell adhesion at the surface of the device. In spite of the good results, scientists aim to create a faster osseointegration, i.e. the connectivity between the medical appliance and the human cells. | |

| One technology currently used is acid-etching – the application of the chemical agents in order to roughen the surface and create a more functional texture and a new topography. | |

| “Such chemical treatments are not biocompatible, and therefore need to be removed before the implantation,” explains Marilys Blanchy. | |

| Another method currently in use is sand blasting, where hard particles are fired onto the surface of the implant to increase its roughness. But here too, experts have raised critical questions, as sand blasting may contaminate the implant’s surface. | |

Nanosized Geometry |

|

| Both these current practices have worked on the micron scale, which is a millionth of a meter, whereas the new laser-based technique will treat the surface on the nano scale, which is a billionth of a meter. The ultra-short pulse laser beams can create regular patterns on the surface, or Laser Induced Periodic Surface Structures (LIPSS), which means the scientists can now adapt a very precise geometry onto the surface and therefore even control the implant's surface topography on the nano-scale. | |

| Cells have the ability to sense these nanostructures. When the implant is inserted, the cells come into contact with its structured surface and are able to proliferate and to spread along the patterns. | |

| “If the implant has a smooth, polished surface, the cells won't adhere well. On the other hand, the cells won't like a spiky surface with harsh edges, either,” points out Blanchy. | |

| The solution is to set up the right topography that will increase the surface contact of the implant and give the cells more space to move around. This technology is also very clean, as it doesn’t change the material's chemical structure. The changes are only mechanical and concern the topography and roughness. | |

| “Instead of having a rough flat surface, we’ll have a surface composed of peaks and valleys,” asserts Marilys Blanchy. | |

How to trick best bone-forming cells |

|

| Using laser treatment for implants is a concept that is also supported by external scientists, not involved in the Laser4Surf project. The bone cells are naturally accustomed to a porous architecture, similar to a bone’s microstructure, and this is why scientists have long tried to mimic natural architectural features onto the implant’s surface, to stimulate cell adhesion. | |

| “How can we “trick” bone-forming cells? One way is to use such laser treatment, preserving the implant's composition while generating some pores at the surface, whose dimensions could be tuned,” says Professor Izabela Stancu, Vice Dean of Research and International Relations at the Faculty of Medical Engineering at the University Politehnica of Bucharest, Romania. | |

| She is a researcher in biomaterials, biofunctionalization and bio-inspired scaffolds. She draws the attention to the type of the roughness obtained after the laser treatments, to which the cells may specifically react. Sometimes, differences of 10 microns or 50 nanometers can be statistically significant in the cellular response. | |

| “The advantage of such laser treatments consists in their flexibility to generate a personalized architecture, enhancing the contact surface between living tissues and synthetic implants. When we talk about the surface engineering of implantable products, whether they use soft or hard tissues, scientists think about the natural features to be mimicked at the tissue-biomaterial interface to trigger cell adhesion. Thus, cells may recognise the implant’s surface as being similar to the natural microenvironment they are familiar with,” explains Prof. Stancu. | |

| Doctors working with implants today, also report failures in the long-term maintenance of the peri-implant (around the implant) health. | |

| “Considering that more than 97% of the implants integrate, our efforts should be focused on preventing peri-implant diseases, which may lead to the progressive loss of osseontegration, leading to bone destruction.“ says Dr Ignacio Sanz Sánchez, Education Programme Mentor at the European Association for Osseointegration, and Professor at the Odontology Faculty, Complutense University of Madrid, Spain. | |

| Since the osseointegration is very predictable, he adds, “Science is progressing in the field of biological implant surfaces, trying to speed up the healing process and to have antibacterial properties in order to prevent peri-implant diseases.” | |

Some more steps to reach the end |

|

| Nevertheless, there are still challenges before the technology adapted by Laser4surf can prove its maximum benefits. Besides the adequate roughness, the titanium implant also needs the right hydrophilicity, which is its capacity to absorb or adsorb water. The cells are very hydrophilic, so a hydrophilic surface helps the cell adhere to the implant's surface. | |

| “Strong roughness might induce certain hydrophobicity (the property of repelling water). So we need to find a compromise between roughness and hydrophilicity. We are working this today and hope to overcome it,” states Marilys Blanchy. | |

| Research on the treatment is still ongoing and the next step will be to along the winding regulatory path. Experiments are being conducted to verify if there are any potential chemical issues that could hinder its acceptance by the human body. In vivo tests in the laboratory will be performed to prove the functionality on different laser induced patterns. | |

| “There are two main advantages of using the laser to treat the implant: firstly, we know the material is biocompatible with the body, and secondly, it will better conform with the related medical regulations. If the chemistry at the surface of the implant has not been changed, the material itself won't have changed, so the product is safe,” adds Blanchy. | |

| It seems like a long way to go, but actually, the first laser treated implants could be at your dentists’ disposal in four or five years' time. | |

| If nano-sized structures on the surfaces of biomaterials are secured using laser technology under the European Laser 4 Surf project, some successful methods are being tested in the laboratory of the Faculty of Medical Engineering in Universitatea Politechnica Bucharest to biodecorate the surface of bone-interactive scaffolds. Amongst these there is the biomimetic coating with nanocomposites based on apatite-like mineral phase. Through the application of apatite particles (a synthetic product, mimicking the mineral component of the hard tissues, hydroxyapatite) on the implant surface, its topography can be changed and a roughness similar to the bone structure can be obtained. |

| Source: By Sorina Buzatu, Laser4Surf | |

|

Subscribe to a free copy of one of our daily Nanowerk Newsletter Email Digests with a compilation of all of the day's news. |