| Jan 18, 2019 | |

Hand-knitted molecules(Nanowerk News) Molecules are usually formed in reaction vessels or laboratory flasks. An Empa research team has now succeeded in producing molecules between two microscopically small, movable gold tips – in a sense as a "hand-knitted" unique specimen. The properties of the molecules can be monitored in real time while they are being produced. The research results have just been published in Nature Communications ("In-situ formation of one-dimensional coordination polymers in molecular junctions"). |

|

|

|

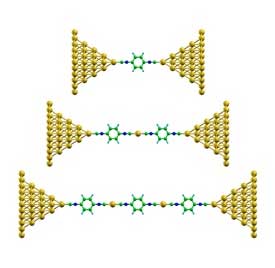

| Hand-knitted molecules: Chains of 1,4-benzenediisocyanate are formed between nanometer-thin gold tips, alternating with individual gold atoms. (© Nature) | |

| The fabrication of electronic components usually follows a top-down pathway in specialized physical laboratories. Using special carving tools in clean rooms, scientists are capable of fabricating structures reaching only a few nanometers. However, atomic precision remains very challenging and usually requires special microscopes such as an Atomic Force Microscope (AFM) or a Scanning Tunneling Microscope (STM). Chemists on the other hand routinely achieve a tour de force: They can synthesize large numbers of molecules that are all exactly identical. But synthesizing a single molecule with atomic precision and monitoring this assembly process remains a formidable challenge. | |

| A research team from Empa, the University of Basel and the University of Oviedo has now succeeded in doing just that: The researchers synthesized chain-shaped molecules between two microscopically small gold tips. Each molecule is created individually. The properties of the resulting molecule can be monitored and documented in real time during synthesis. | |

Micro-manufactory between gold tips |

|

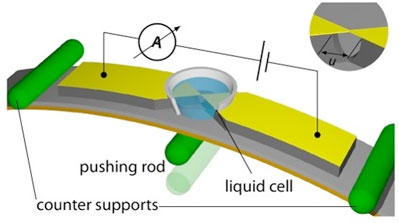

| Anton Vladyka, Jan Overbeck and Mickael Perrin work at Empa's "Transport at Nanoscale Interfaces" laboratory, headed by Michel Calame. For their experiments, they used a technique called mechanically controllable break junction (MCBJ). A gold bridge only a few nanometers thin is slowly stretched in a reagent solution until it breaks. Individual molecules can attach themselves to the fracture tips of the nano-bridge and undergo chemical reactions. | |

| Empa researchers dipped the gold tips in a solution of 1,4-diisocyanobenzene (DICB), a molecule with strong electrical dipoles at both ends. These highly charged ends readily bond with gold atoms. The result: When the bridge is torn apart, a DICB molecule detaches individual gold atoms from the contact and thus builds a molecular chain. Each DICB molecule is followed by a gold atom, followed by another DICB molecule, a gold atom, and so on. | |

|

|

| Experimental setup: The gold bridge, which is only a few nanometers thin, is surrounded by a reagent liquid and is repeatedly opened and closed by micromechanics – up to 50 times. At the same time, the electrical conductivity is measured. Molecular chains form between the gold tips. (© Nature) | |

High success rate |

|

| What is remarkable: the molecular assembly was not dependent on any coincidences, but worked highly reproducible – even at room temperature. The researchers repeatedly opened and closed the gold bridge to better understand the process. | |

| In 99 out of 100 trials identical molecular chains of gold and DICB were formed. By monitoring the electrical conductivity between the gold contacts the researchers were even able to determine the length of the chain. Up to three chain links can be detected. If four or more chain links are formed, the conductivity is too low and the molecule remains invisible during this experiment. | |

Basis for chemical and physical analyses |

|

| This new method allows researchers to produce electrically conductive molecules as unique specimens and to characterize them using a variety of methods. This opens up completely new possibilities to change the electrical properties of individual molecules directly ("in situ") and to adjust them with atomic precision. This is considered a crucial step towards the further miniaturization of electronic components. At the same time, it offers deep insights into transport processes at the atomic level. | |

| "In order to discover new properties in molecular assemblies, we must first be able to build these molecular structures in a reproducible manner," says Michel Calame. "This is exactly what we have now achieved.” |

| Source: Empa | |

|

Subscribe to a free copy of one of our daily Nanowerk Newsletter Email Digests with a compilation of all of the day's news. |