| Apr 07, 2020 | |

Engineers 'program' liquid crystalline elastomers to replicate complex twisting action simply with the use of light(Nanowerk News) The twisting and bending capabilities of the human muscle system enable a varied and dynamic range of motion, from walking and running to reaching and grasping. Replicating something as seemingly simple as waving a hand in a robot, however, requires a complex series of motors, pumps, actuators and algorithms. |

|

| Researchers at the University of Pittsburgh and Harvard University have recently designed a polymer known as a liquid crystal elastomer (LCE) that can be "programmed" to both twist and bend in the presence of light. | |

| The research, published in the journal Science Advances ("Twist again: Dynamically and reversibly controllable chirality in liquid crystalline elastomer microposts"), was developed at Pitt's Swanson School of Engineering by Anna C. Balazs, Distinguished Professor of Chemical and Petroleum Engineering and John A. Swanson Chair of Engineering; and James T. Waters, postdoctoral associate and the paper's first author. Other researchers from Harvard University's Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering and the John A. Paulson School of Engineering include Joanna Aizenberg, Michael Aizenberg, Michael Lerch, Shucong Li and Yuxing Yao. | |

|

|

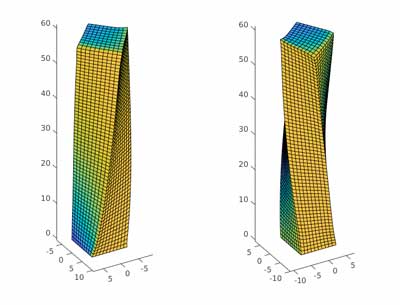

| A simulated liquid crystal elastomer micropost with the nematic director oriented at 45 degrees relative to the flat surface. Illuminating one side of the post induces the top of the post to twist relative to the fixed base. Illuminating the opposite face of the post results in a twist in the opposite direction. Color indicates the regions of the post that are illuminated (yellow) or in shadow (blue). (Image: Balazs Lab) | |

| These particular LCEs are achiral: the structure and its mirror image are identical. This is not true for a chiral object, such as a human hand, which is not superimposable with a mirror image of itself. In other words, the right hand cannot be spontaneously converted to a left hand. When the achiral LCE is exposed to light, however, it can controllably and reversibly twist to the right or twist to left, forming both right-handed and left-handed structures. | |

| "The chirality of molecules and materials systems often dictates their properties," Dr. Balazs explained. "The ability to dynamically and reversibly alter chirality or drive an achiral structure into a chiral one could provide a unique approach for changing the properties of a given system on-the-fly." To date, however, achieving this level of structural mutability remains a daunting challenge. Hence, these findings are exciting because these LCEs are inherently achiral but can become chiral in the presence of ultraviolet light and revert to achiral when the light is removed." | |

| The researchers uncovered this distinctive dynamic behavior through their computer modeling of a microscopic LCE post anchored to a surface in air. Molecules (the mesogens) that extend from the LCE backbone are all aligned at 45 degrees (with respect to the surface) by a magnetic field; in addition, the LCEs are cross-linked with a light-sensitive material. | |

| "When we simulated shining a light in one direction, the LCE molecules would become disorganized and the entire LCE post twists to the left; shine it in the opposite direction and it twists to the right," Dr. Waters described. These modeling results were corroborated by the experimental findings from the Harvard group. | |

| Going a step further, the researchers used their validated computer model to design "chimera" LCE posts where the molecules in the top half of the post are aligned in one direction and are aligned in another direction in the bottom half. With the application of light, these chimera structures can simultaneously bend and twist, mimicking the complex motion enabled by the human muscular system. | |

| "This is much like how a puppeteer controls a marionette, but in this instance the light serves as the strings, and we can create dynamic and reversible movements through coupling chemical, optical, and mechanical energy," Dr. Balazs said. "Being able to understand how to design artificial systems with this complex integration is fundamental to creating adaptive materials that can respond to changes in the environment. Especially in the field of soft robotics, this is essential for building devices that exhibit controllable, dynamic behavior without the need for complex electronic components." |

| Source: University of Pittsburgh | |

|

Subscribe to a free copy of one of our daily Nanowerk Newsletter Email Digests with a compilation of all of the day's news. |