| Apr 18, 2023 |

Nanocellulose wound dressing that can reveal infection

(Nanowerk News) A nanocellulose wound dressing that can reveal early signs of infection without interfering with the healing process has been developed by researchers at Linköping University, Sweden. Their study, published in Materials Today Bio ("Nanocellulose composite wound dressings for real-time pH wound monitoring"), is one further step on the road to a new type of wound care.

|

|

The skin is the largest organ of the human body. A wound disrupts the normal function of the skin and can take a long time to heal, be very painful for the patient and may, in a worst case scenario, lead to death if not treated correctly. Also, hard-to-heal wounds pose a great burden on society, representing about half of all costs in out-patient care.

|

|

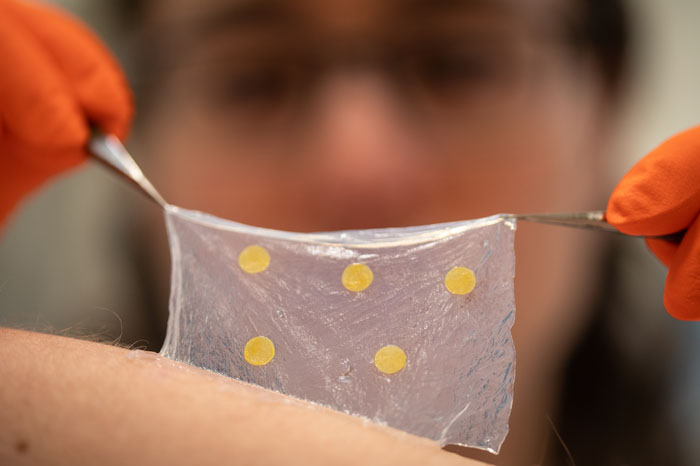

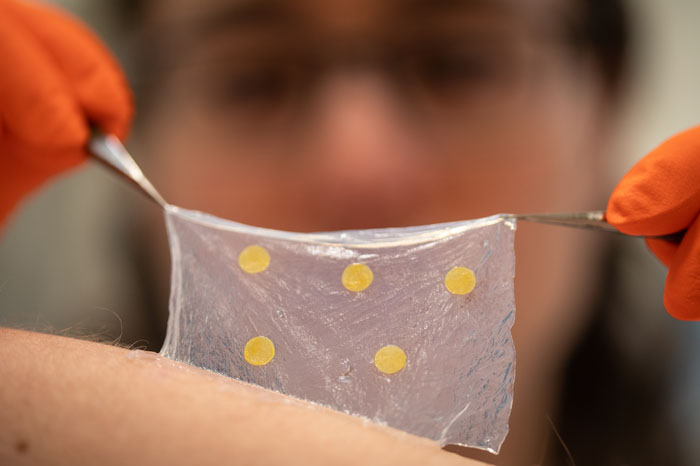

| A nanocellulose wound dressing that can reveal early signs of infection through a shift in colour. (Image: Olov Planthaber)

|

|

In traditional wound care, dressings are changed regularly, about every two days. To check whether the wound is infected, care staff have to lift the dressing and make an assessment based on appearance and tests. This is a painful procedure that disturbs wound healing as the scab breaks repeatedly. The risk of infection also increases every time the wound is exposed.

|

|

Researchers at Linköping University, in collaboration with colleagues from Örebro and Luleå Universities, have now developed a wound dressing made of nanocellulose that can reveal early signs of infection without interfering with the healing process.

|

|

“Being able to see instantly whether a wound has become infected, without having to lift the dressing, opens up for a new type of wound care that can lead to more efficient care and improve life for patients with hard-to-heal wounds. It can also reduce unnecessary use of antibiotics,” says Daniel Aili, professor in the Division of Biophysics and Bioengineering at Linköping University.

|

|

The dressing is made of tight mesh nanocellulose, preventing bacteria and other microbes from getting in. At the same time, the material lets gases and liquid through, something that is important to wound healing. The idea is that once applied, the dressing will stay on during the entire healing process. Should the wound become infected, the dressing will show a colour shift.

|

|

Non-infected wounds have a pH value of about 5.5. When an infection occurs, the wound becomes increasingly basic and may have a pH value of 8, or even higher. This is because bacteria in the wound change their surroundings to fit their optimal growth environment. An elevated pH value in the wound can be detected long before any pus, soreness or redness, which are the most common signs of infection.

|

|

To make the wound dressing show the elevated pH value, the researchers used bromthymol blue, BTB, a dye that changes colour from yellow to blue when the pH value exceeds 7. For BTB to be used in the dressing without being compromised, it was loaded onto a silica material with pores only a few nanometres in size. The silica material could then be combined with the dressing material without compromising the nanocellulose. The result is a wound dressing that turns blue when there is an infection.

|

|

Wound infections are often treated with antibiotics that spread throughout the body. But if the infection is detected at an early stage, local treatment of the wound may suffice. This is why Daniel Aili and his colleagues at Örebro University are also developing anti-microbial substances based on so-called lipopeptides that kill off all types of bacteria.

|

|

“The use of antibiotics makes infections increasingly problematic, as multi-resistant bacteria are becoming more common. If we can combine the anti-microbial substance with the dressing, we minimise the risk of infection and reduce the overuse of antibiotics,” says Daniel Aili.

|

|

Daniel Aili says that the new wound dressing and the anti-microbial substance are part of developing a new type of wound treatment in out-patient care. But as all products to be used in medical care settings have to pass rigorous and expensive testing, he thinks that it will be five to ten years before it will be available there.

|