| Posted: June 2, 2010 |

Single-molecule manipulation for the masses |

|

(Nanowerk News) Scientists have developed a new massively-parallel approach for manipulating single DNA and protein molecules and studying their interactions under force. The finding appears in the June 2 issue of Biophysical Journal. The team of researchers from the Rowland Institute at Harvard University claim that their technique, which they call "single molecule centrifugation", offers dramatic improvements in throughput and cost compared with more established techniques.

|

|

"By combining a microscope and a centrifuge, forces can be applied to many molecules at once while simultaneously observing their nano-to-microscale motions," explains author Wesley P. Wong, a Principal Investigator at Rowland.

|

|

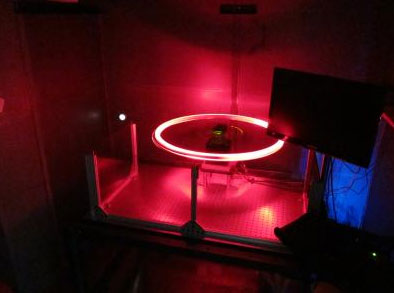

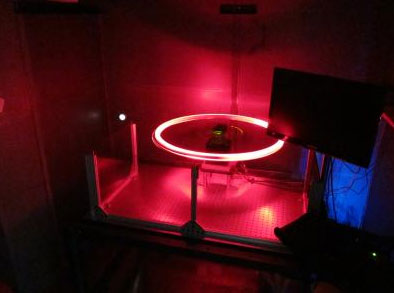

| This is the Centrifuge Force Micoscope in action.

|

|

Recent technologies such as optical and magnetic tweezers and the Atomic Force Microscope (AFM) have enabled the mechanical manipulation of single molecules, leading to new insights in biological systems ranging from DNA replication to blood clotting.

|

|

However, the tools used to perform these experiments are often expensive and can be tedious and complicated to use, limiting their use among scientists.

|

|

The Harvard researchers aimed to solve these problems by developing an instrument they call the Centrifuge Force Microscope (CFM), which uses centrifugal force to manipulate molecules.

|

|

Developing the instrument involved miniaturizing a light microscope and safely rotating it at high speeds while maintaining precision and control.

|

|

Experiments involve tethering thousands of micron-sized "carrier" particles to a surface and observing their motion as the sample rotates to generate the centrifugal force.

|

|

"We're really excited about this new method," says co-author Ken Halvorsen, a postdoctoral fellow. "After doing tedious single-molecule experiments for years, we thought there had to be a better way. Now, instead of doing one experiment thousands of times we can do thousands of experiments at once."

|

|

The scientists expect that the relative low cost and simplicity of the method will attract researchers who may be intimidated by the cost and technical skills required for other methods, ultimately enabling new discoveries in both health and basic science research.

|