| Posted: August 16, 2010 |

Nanocorrosion causes implants to fail |

|

(Nanowerk News) Extra-hard coatings made from diamond-like carbon (DLC) extend the operating lifetime of tools and components. In artificial joints, however, these coatings often fail because they detach. Empa

researchers found out why – and developed methods to both make the interface between the DLC

layer and the metal underneath corrosion-resistant and to predict the lifetime of the implants.

|

|

Whether on computer hard disks, saw blades, embossing tools, razor blades or fuel-injection nozzles,

extremely hard coatings made of diamond-like carbon (DLC) have proven their value over and over again.

They reduce wear and thereby give tools and components a longer operating lifetime. What could be more

logical than to apply DLC to medical implants such as artificial joints, reasoned a number of implant

manufacturers. After all, wear is a problem there, too.

|

|

DLC has subsequently withstood endless in vitro tests in several manufacturers' laboratories and has shown

itself to be well tolerated by human tissue, extremely hard wearing, and resistant to the relatively aggressive

environment in the human body. Despite this, when DLC-coated joints were first implanted into human

patients, serious problems arose after only a few years. The DLC coatings were not worn away, but rather

they detached from the implant material for no apparent reason.

|

|

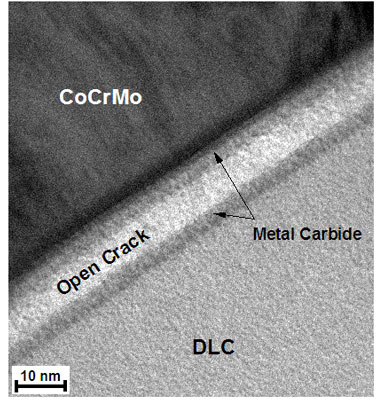

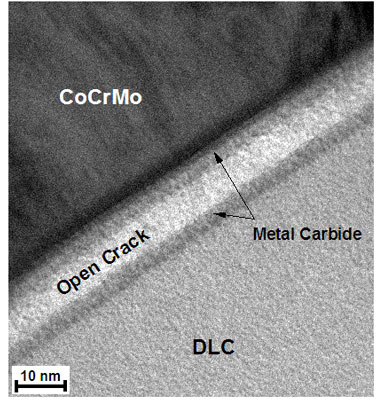

| Under physiological conditions, stress corrosion cracking leads to a slow-growing crack in the metal carbide

reaction layer, which is barely 5 nanometers wide. This, in turn, causes the DLC layer to detach from the

implant material (cobalt-chrome-molybdenum, CoCrMo), as seen in a transmission electron microscope

image.

|

|

Taking aims at the interface

|

|

In a project financed by the Swiss Innovation Promotion Agency (CTI) together with the medical technology

company Synthes and the coating company Ionbond AG, Empa researchers sought out the cause of this

detachment. For this, the researchers conducted detailed studies of the interface between the implant

material and the coating. "When two materials are placed in contact with each other, the result is a reaction

layer at the interface between them, which is only several atomic layers thick. Thus a new material is formed,

which we investigated now for the first time", explains Roland Hauert of Empa's "Nanoscale Materials

Science" laboratory.

|

|

His team showed that the so far barely considered reaction layer, which is not always completely corrosion

resistant, is responsible for the detachment of the DLC layer. On the one hand, stress corrosion cracking

occurred in the reaction layer. The mechanical load in conjunction with the penetration of body fluids led to

slow-growing cracks, which in turn caused the DLC substrate to detach little by little.

|

|

In other cases, crevice corrosion was responsible for the damage. Over time, an aggressive, acidic medium

develops in fine crevices and slowly dissolves the reaction layer or the additional adhesive layer, likewise

leading to detachment.

|

|

Methods to determine operating lifetime

|

|

But the Empa team didn't stop there; together with their industry partners Synthes and Ionbond, they

developed a corrosion-resistant intermediate layer at the interface to the DLC layer. What's more, the

researchers also developed a process that can determine a crack's growth rate under conditions similar to

those experienced in the human body as well as the dissolution rate of the reaction layer in cases of crevice

corrosion. "This then allows us to calculate the expected operating lifetime of the coated implant in the

human body", says Roland Hauert. Whether or not a DLC-coated implant will fail prematurely in vivo can

henceforth already be determined during the development of the product.

|