| Posted: September 2, 2010 |

Researchers illuminate operation of molecular gateway to the cell nucleus |

|

(Nanowerk News) QB3 biophysicists have traced with unprecedented resolution the paths of cargos moving through the nuclear pore complex (NPC), a selective nanoscale aperture that controls access to the cell's nucleus, and answered several key questions about its function.

|

|

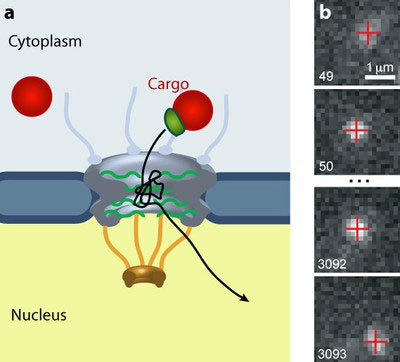

The NPC, a large protein assembly shaped like a basketball net fringed with tentacles, is the gateway to the cell nucleus, where genetic information is stored. Each cell nucleus contains roughly 2,000 NPCs, embedded in the nuclear envelope. The NPC (which is about 50 nanometers wide) is responsible for all transport into and out of the nucleus. To prevent the contents of the rest of the cell's interior from mixing with that of the nucleus, the NPC discriminates between cargos with great precision.

|

|

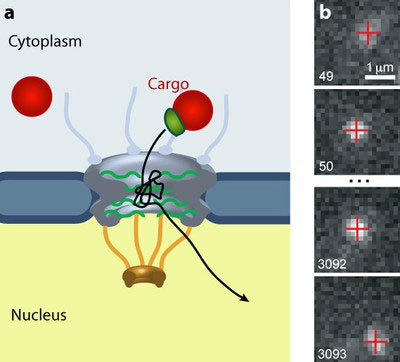

| The nuclear pore complex (NPC) gates the traffic of all molecules between the cytoplasm and the nucleus of eukaryotic cells. (a) Larger cargos (red) require a transport receptor (green) to pass through the gate. (b) A quantum dot cargo moves through an NPC. (Image: Alan Lowe)

|

|

Several viruses target the NPC to gain entry to the nucleus, and dysfunctional transport between the cytoplasm and the nucleus has been implicated in multiple diseases including cancer.

|

|

Scientists have constructed models for the NPC, but how this channel operates and achieves its selectivity has remained a mystery. It is known that, to make it through the NPC, large molecules must bind at least a few receptors called "importins"; whether binding more importins speeds or slows a molecule's passage has been unclear. So, too, has the exact point at which a carrier protein called "Ran" plays a crucial part, substituting one molecule of GTP (a cellular fuel, an analog of the better-known ATP) for one of GDP that the large molecule brings with it when it enters the NPC.

|

|

Karsten Weis, a UC Berkeley professor of molecular and cell biology, Jan Liphardt, a UC Berkeley professor of physics, and colleagues conducted advanced imaging experiments that resolved these issues. (Weis and Liphardt are members of QB3.) The research was published September 1st in the journal Nature, in a paper on which Berkeley post-doc Alan Lowe and graduate student Jake Siegel were joint first authors.

|

|

Previously, scientists had observed the motion of small molecules (a few nm in diameter), labeled with fluorescent tags, through the NPC. But the rapid transit and faint signal of these molecules resulted in sparse, fuzzy data. Lowe, Siegel, et al. employed "quantum dots", which are about 20 nm in diameter—and hence slower than smaller molecules—and much brighter than conventional fluorophores. The researchers coated the quantum dots with signals recognized by importins. Using a microscopic technique that allowed them to see a flat, thin visual slice through living cells, they watched hundreds of individual dots entering, jiggling around in, being ejected from, and in some cases admitted through, NPCs. The researchers recorded video data and tracked the motion of 849 quantum dots with nanometer precision.

|

|

The spaghetti-like paths of the quantum dots, superimposed on one another, revealed that the particles fell into three classes: "early aborts," which were briefly confined and then bounced out; "late aborts," which wandered in and meandered to the inner end of the pore before exiting the way they came; and "successes," which followed much the same paths as the late aborts but were granted entry.

|

|

From the paths' erratic meanderings, the researchers deduced that the quantum dots were indeed diffusing randomly, rather than being actively transported. And adding more importins to the dots' coating shortened the transit time, suggesting that importins make incoming cargo more soluble within the NPC rather than binding to interior walls.

|

|

The researchers found a particularly interesting result when they withheld the carrier protein Ran from the experiment. Without Ran in the mix, the quantum dots followed exactly the same range of paths as when Ran was present, except that virtually none passed through the NPC.

|

|

Considering their path data, the authors drew a model for how the NPC operates. Large cargo is initially captured by the NPC's filament fringe. It then encounters a constriction, through which it can enter a sort of antechamber. Then, in certain cases, Ran exchanges the cargo's GDP for a GTP and it is admitted into the nucleus. Only the final step is irreversible.

|

|

"It's an elegant study," says Michael Rout, a professor of cellular and structural biology at The Rockefeller University whose specialty is NPC transport. "If we do eventually understand how the NPC operates at the subtlest level, we could perhaps build filters to select molecules of interest."

|

|

Indeed, one of the main new insights is that the NPC's selectivity seems to result from a cascade of filters, each preferring correct cargos, rather than just one very selective step. This helps explain why some things can easily get into the nucleus and other things are excluded. This discovery may have some very practical clinical implications, Liphardt and Weis say. It may enable scientists to develop techniques to efficiently deliver large man-made cargos, such as drug-polymer conjugates and contrast agents, to the nucleus, which contains the genome.

|