| Nov 09, 2010 |

New drugs, materials unveiled at nanotechnology conference in Israel

|

|

(Nanowerk News) A material just one atom thick that is stronger than steel but flexes like rubber. A "mini-submarine" that can trick the immune system and deliver a payload of chemotherapy deep inside a tumour.

|

|

They sound like the fantasies of science fiction writers, but they are among the discoveries being presented at Nano Israel 2010, a nanotech conference in Tel Aviv that has attracted researchers from across the science world, united by their work with the very, very small.

|

|

The 1,500 participants at the two-day meeting which ends on Tuesday include chemists, physicists and medical researchers, all working with tiny structures around the thickness of a cell wall.

|

|

"We are all working to be able to manipulate molecules at an atomic level," said Dan Peer, a professor at Tel Aviv University's Cell Research and Immunology Department.

|

|

Physicists are developing new materials by removing or adding to existing structures and nano-medical researchers are building new ways to deliver drugs.

|

|

Peer is trying to find out how to more effectively target cancer and the inflammation associated with diseases like multiple sclerosis by better directing toxic treatments like chemotherapy.

|

|

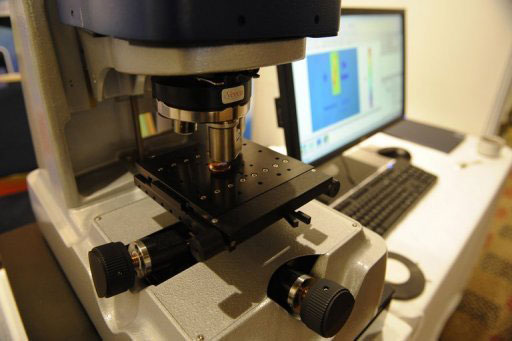

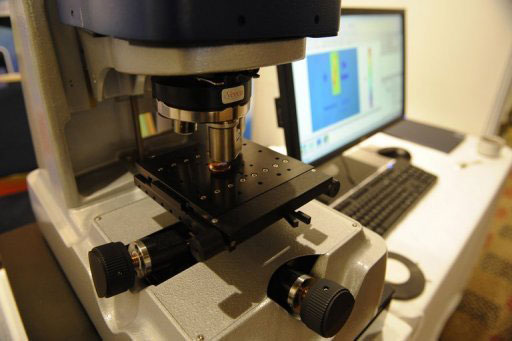

| A Euro coin is scanned at the Nano Israel 2010 conference in Tel Aviv.

|

|

"Sometimes the drug is there, but it doesn't operate in a targeted manner," he told AFP.

|

|

In such cases, scientists are trying to find ways to build "GPS systems" into the drugs so they travel directly to malignant cells or inflammation.

|

|

One way of doing that is to attach the cancer treatment to a vitamin that tumours happily suck up, allowing the medication to penetrate the malignant cells with ease.

|

|

"You can potentially create new materials, new vehicles for drugs, like very small bubbles, like mini-submarines, which carry them into the body," Peer told AFP.

|

|

Joseph Kost, a professor at Ben Gurion University of the Negev's chemical engineering department, is working on a technique that delivers chemotherapy drug Cisplatin into tumours.

|

|

The drug is carried by a tiny vessel through gaps of between 100-1000 nanometres in size, giving scientists a "therapeutic warhead," he said.

|

|

Once inside, researchers irradiate the drug vehicles with ultrasound, causing them to "explode" and disperse the treatment inside the tumour.

|

|

Others are looking at ways to trick the body's immune system to prevent it from identifying drug treatments as invading viruses and attacking them.

|

|

Elsewhere, physicists like Andre Geim, winner of this year's Nobel Prize for Physics, are using nanotechnology to develop new materials with a surprising range of applications.

|

|

Geim, a Russian scientist working in Britain, presented his work on graphene, a one-atom-thick slice of graphite that is stiffer than diamond.

|

|

"You can imagine you can make a thousand devices out of this graphene," he told an audience of researchers from 35 countries, whose work could one day produce more efficient conductors and roll-up touchscreens for computers.

|

|

Graphene's structure could even allow it to be used for faster DNA sequencing, Geim said.

|

|

For Israel, hosting the gathering of nano-researchers is a way of showcasing a sector that the government is trying to foster.

|

|

|

|

"We see this as a major economic initiative for the future of Israel," said Barry Breen, a spokesman for Israel's National Nanotechnology Initiative, a government advisory body. "It should be a dominant economic engine."

|

|

INNI works to match Israel's nanotech researchers with private industry.

|

|

A recent project saw Jerusalem-based company 3G Solar work with scientists at Bar Ilan University to develop a solar cell that processes energy in a similar way to photosynthesis in plants.

|

|

Aharon Gedanken, a professor of chemistry at Bar Ilan University, is using nanotechnology to develop sterile hospital sheets and robes using a technique called sonochemistry.

|

|

The process uses a chemical reaction that produces "microjets," which throw out nanoparticles of anti-bacterial metals like zinc oxide at "such a high speed that they are embedded in the surface."

|

|

The resulting fabric can be washed, even at the hospital standard of 92 degrees Celsius (197.6 degrees Fahrenheit), without losing its anti-bacterial properties.

|

|

"The vision of this project is that in the future all the fabrics in a hospital will be anti-bacterial," he said.

|