| May 10, 2011 |

Pairing quantum dots with fullerenes for nanoscale photovoltaics

|

|

(Nanowerk News) In a step toward engineering ever-smaller electronic devices, scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory have assembled nanoscale pairings of particles that show promise as miniaturized power sources. Composed of light-absorbing, colloidal quantum dots linked to carbon-based fullerene nanoparticles, these tiny two-particle systems can convert light to electricity in a precisely controlled way.

|

|

"This is the first demonstration of a hybrid inorganic/organic, dimeric (two-particle) material that acts as an electron donor-bridge-acceptor system for converting light to electrical current," said Brookhaven physical chemist Mircea Cotlet, lead author of a paper describing the dimers and their assembly method in Angewandte Chemie.

|

|

| Mircea Cotlet (standing) and Zhihua Xu

|

|

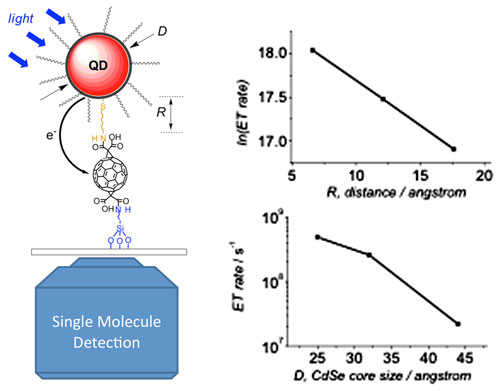

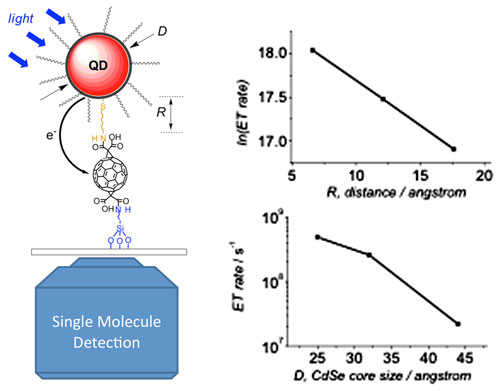

By varying the length of the linker molecules and the size of the quantum dots, the scientists can control the rate and the magnitude of fluctuations in light-induced electron transfer at the level of the individual dimer. "This control makes these dimers promising power-generating units for molecular electronics or more efficient photovoltaic solar cells," said Cotlet, who conducted this research with materials scientist Zhihua Xu at Brookhaven's Center for Functional Nanomaterials (CFN).

|

|

Scientists seeking to develop molecular electronics have been very interested in organic donor-bridge-acceptor systems because they have a wide range of charge transport mechanisms and because their charge-transfer properties can be controlled by varying their chemistry. Recently, quantum dots have been combined with electron-accepting materials such as dyes, fullerenes, and titanium oxide to produce dye-sensitized and hybrid solar cells in the hope that the light-absorbing and size-dependent emission properties of quantum dots would boost the efficiency of such devices. But so far, the power conversion rates of these systems have remained quite low.

|

|

Click on the image to download a high-resolution version.Left: Photoinduced electron transfer occurring in quantum dot-bridge-fullerene hererodimers and observed with single molecule microscopy. Right: Control of electron transfer (ET) rate by variation of interparticle distance (R, upper panel) and quantum dot size (D, lower panel).

|

|

"Efforts to understand the processes involved so as to engineer improved systems have generally looked at averaged behavior in blended or layer-by-layer structures rather than the response of individual, well-controlled hybrid donor-acceptor architectures," said Xu.

|

|

The precision fabrication method developed by the Brookhaven scientists allows them to carefully control particle size and interparticle distance so they can explore conditions for light-induced electron transfer between individual quantum dots and electron-accepting fullerenes at the single molecule level.

|

|

The entire assembly process takes place on a surface and in a stepwise fashion to limit the interactions of the components (particles), which could otherwise combine in a number of ways if assembled by solution-based methods. This surface-based assembly also achieves controlled, one-to-one nanoparticle pairing.

|

|

| Left: Photoinduced electron transfer occurring in quantum dot-bridge-fullerene hererodimers and observed with single molecule microscopy. Right: Control of electron transfer (ET) rate by variation of interparticle distance (R, upper panel) and quantum dot size (D, lower panel).

|

|

To identify the optimal architectural arrangement for the particles, the scientists strategically varied the size of the quantum dots ? which absorb and emit light at different frequencies according to their size ? and the length of the bridge molecules connecting the nanoparticles. For each arrangement, they measured the electron transfer rate using single molecule spectroscopy.

|

|

"This method removes ensemble averaging and reveals a system's heterogeneity ? for example fluctuating electron transfer rates ? which is something that conventional spectroscopic methods cannot always do," Cotlet said.

|

|

The scientists found that reducing quantum dot size and the length of the linker molecules led to enhancements in the electron transfer rate and suppression of electron transfer fluctuations.

|

|

"This suppression of electron transfer fluctuation in dimers with smaller quantum dot size leads to a stable charge generation rate, which can have a positive impact on the application of these dimers in molecular electronics, including potentially in miniature and large-area photovoltaics," Cotlet said.

|

|

"Studying the charge separation and recombination processes in these simplified and well-controlled dimer structures helps us to understand the more complicated photon-to-electron conversion processes in large-area solar cells, and eventually improve their photovoltaic efficiency," Xu added.

|

|

A U.S. patent application is pending on the method and the materials resulting from using the technique, and the technology is available for licensing. Please contact Kimberley Elcess at (631) 344-4151 for more information.

|