| Jun 06, 2011 |

Microscopy with a quantum tip

|

|

(Nanowerk News) Microscopes make tiny objects visible, as their name suggests. However, modern microscopes often do this in a round-about way, not by optically imaging the object with light, but by probing the surface with a fine, needle-like tip. Here, where optical imaging methods reach their limits, scanning probe microscopes can show, by different methods, structures as small as one millionth of a millimetre. With their help, phenomena in the nanoworld become visible and targeted manipulation becomes possible. The heart of a scanning probe microscope is a moveable, suspended tip, which, like the needle on a record player, reacts to small height variations on the surface, and turns these into signals that can be displayed on a computer.

|

|

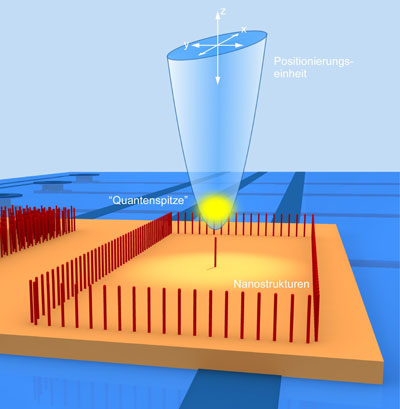

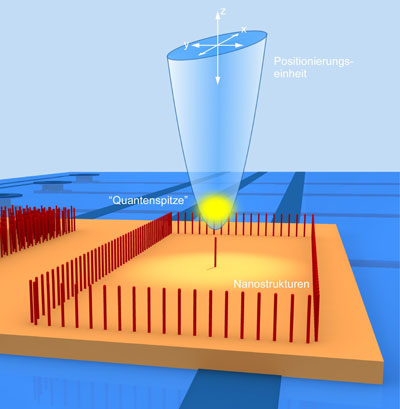

Tübingen researchers have now been able to create this tip, not out of solid material, as in the case of the record player, but out of an ultra-cold, dilute gas of atoms. To do this, they cooled an especially pure gas of rubidium atoms to a temperature less than a millionth of a degree above absolute zero temperature, and stored the atoms in a magnetic trap. This "quantum tip" can be precisely positioned and enables the probing of nanostructured surfaces. With this method, more accurate measurements of the interactions between atoms and surfaces are possible and further cooling of the probe tip gives rise to a so-called Bose-Einstein condensate, which allows a significant increase in the resolution of the microscope.

|

|

| An ultra-cold cloud of atoms (yellow) is trapped in a magnetic trap and scanned across a nanostruc-tured surface. In "contact mode" a loss of atoms from the cloud can be measured, which depends on the surface topography. In the "dynamical mode" the frequency and amplitude of the cloud's cen-tre-of-mass oscillation changes depending on the surface structure. Both methods allow the surface topography to be imaged.

|

|

The work was led by Prof. Dr. József Fortágh, head of the Nano-Atom-Optics group, and his co-worker Dr. Andreas Günther. PhD student Michael Gierling is first author of the study, which appeared on May 29 as an advance online publication in the scientific journal Nature Nanotechnology ("Cold-atom scanning probe microscopy").

|

|

The scientists demonstrated the use of their cold-atom scanning probe tip by testing a surface with vertically grown carbon nanotubes. The tip was scanned over the sample using a type of magnetic conveyor belt. The first measurements in the so-called "contact mode" revealed how the tall tubes stripped some atoms out of the atom cloud. These atom losses told the researchers about the location and height of the nanotubes and enabled the imaging of the surface topography.

|

|

When the temperature of an atomic gas approaches absolute zero, a quantum mechanical phenomenon occurs, turning the cloud into what's known as a Bose-Einstein condensate. In this state it is no longer possible to distinguish between the atoms. They become, so to speak, a single, giant "super-atom". With such a Bose-Einstein condensate it was possible for the Tübingen scientists to microscopically resolve individual freestanding nanotubes. According to the researchers, future improvements to the cold-atom scanning probe microscope could, in theory, increase the current resolution of about eight micrometres by a factor of a thousand.

|

|

The microscope also functions in the so-called "dynamical mode". The researchers again created a Bose-Einstein condensate close to the nanotubes. They then allowed the condensate to oscillate perpendicular to the surface, and observed how the frequency and size of these oscillations changed, depending on the topography of the nanostructured sample. In this way they were able to obtain a well resolved image of the surface. The researchers write that this method has an advantage because no atoms are loss from the cloud. This could be helpful in cases where atoms that are adsorbed on the sample might influence subsequent measurements.

|

|

The researchers conclude: "the extreme purity of the probe tip and quantum control over the atomic states in a Bose-Einstein condensate open up new possibilities of scanning probe microscopy with non-classical probe tips". Beyond this, the researchers hope to develop new applications from the demonstrated coupling between ultra-cold quantum gases and nanostructures.

|

|

The study was done within the framework of the BMBF programme "NanoFutur" and in collaboration with several groups from the Center for Collective Quantum Phenomena (CQ) Tübingen, to which various research groups from the Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Science belong.

|