| Sep 19, 2011 |

A new way to go from nanoparticles to supraparticles

|

|

(Nanowerk News) Controlling the behavior of nanoparticles can be just as difficult trying to wrangle a group of teenagers. However, a new study involving the U.S. Department of Energy's Argonne National Laboratory has given scientists insight into how tweaking a nanoparticle's attractive electronic qualities can lead to the creation of ordered uniform "supraparticles" ("Self-assembly of self-limiting monodisperse supraparticles from polydisperse nanoparticles").

|

|

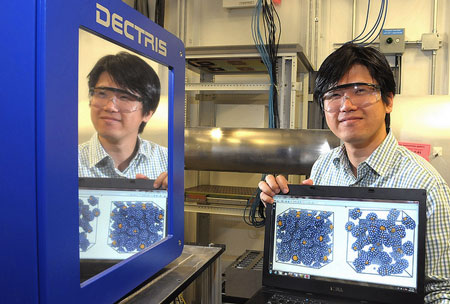

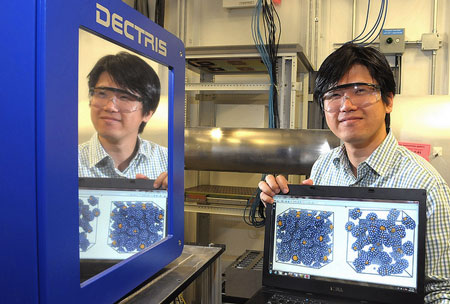

"There's a delicate balance you have to strike," said Argonne physicist Byeongdu Lee, who led the characterization of the supraparticles using high-energy X-rays provided by Argonne's Advanced Photon Source. "If the attractive Van der Waals force is too strong, all the nanoparticles will smash together at once, and you'll end up with an ugly, disordered glass. But if the repulsive Coulomb force is too strong, they'll never come together in the first place."

|

|

| "There's a delicate balance you have to strike," said Argonne physicist Byeongdu Lee, who led the characterization of the supraparticles using high-energy X-rays provided by Argonne's Advanced Photon Source. "If the attractive Van der Waals force is too strong, all the nanoparticles will smash together at once, and you'll end up with an ugly, disordered glass. But if the repulsive Coulomb force is too strong, they'll never come together in the first place."

|

|

Researchers from the University of Michigan and China also collaborated on the study.

|

|

This problem of trying to achieve the right kind of balance has underpinned an entire field of colloidal research, according to Lee. But even if the right equilibrium is struck to promote the slow, steady growth of a supraparticle, up until now researchers have still had very little way of controlling the size of the particle that would grow. "If you were able to make the attractive force just a little stronger than the repulsive force, you'd see the growth of a crystal—but you wouldn't be able to dictate how big it grew," he said.

|

|

The Argonne research focused on finding a way for a supraparticle to automatically stop its own growth. Such a condition could only occur if the net attractive force of the nanoparticles toward the inside of the supraparticle was greater than that of the net attractive force of the nanoparticles that formed the edge of the supraparticle—a so-called "core-shell morphology."

|

|

Although core-shell morphologies had been observed in previous research, those earlier studies had concentrated on the types of supraparticles created by "monodisperse" nanoparticles—those that, like marbles, would share a common size and shape. "It's easier to make individuals cluster into larger groups if they have characteristics in common than if they don't," Lee said. "It is just like high school in that way."

|

|

Instead of sticking with monodispersity, however, the Argonne research focused instead on "polydisperse" nanoparticles—those with a wide variety of sizes, masses, and configurations. "The advantage with our technique is that there's no longer a need for monodispersity. You can mix two different components—like a metal and a semiconductor—and still see the same kind of controlled self-limiting assembly."

|

|

Although the research into supraparticles born from polydisperse collections of nanoparticles is still in its infancy, Lee and his colleagues believe that the methodology could find its way into a number of different applications, perhaps ranging from optics to drug delivery to photovoltaics. "When you work in nanotechnology, we have to ask 'can we do this?' before we really know what our discovery will be useful for," explained Lee. "We hope that further investigation will open up new lines of discovery that we have not even conceived of yet."

|