| Oct 26, 2011 |

Photonics: In the crossfire

|

|

(Nanowerk News) Light and electric current can both be used for computing, albeit with key differences. Whereas conventional computers do logic through the movement of electrons, newer and faster computers called quantum computers perform the same job using single particles of light, known as photons.

|

|

The use of photons, however, is not without its problems. One major obstacle has been the limited capability of photon detectors to reliably count the number of photons in a light beam. Dmitry Kalashnikov at the A*STAR Data Storage Institute and co-workers have now proposed a scheme to improve the counting precision of photon detectors ("Accessing photon bunching with a photon number resolving multi-pixel detector").

|

|

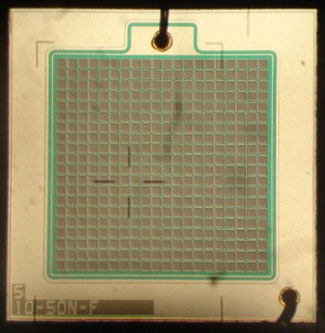

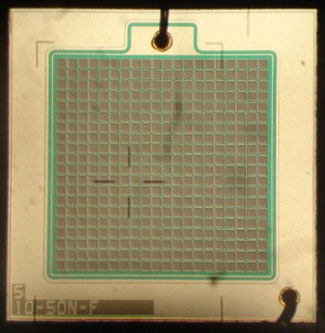

The performance of most photon detectors is limited due to the inherent difficulties involved in detecting tiny signals caused by the absorption of single photons. One way to overcome this problem is to use an 'avalanche' photon detector, in which a single photon triggers an amplified number of electrons in the device through the process of avalanche multiplication. Several hundreds of these detectors can be packed into an array to form a multi-photon pixel counter (MPPC) (see image).

|

|

| An MPPC detector consisting of an array of avalanche photodiodes.

|

|

However, MPPCs also have their limitations. "A significant drawback for MPPC is cross-talk. When an MPPC detects a photon, the electrical avalanche is accompanied by the emission of secondary photons, which cause signals in neighboring pixels," says Kalashnikov. In order to 'filter out' this cross-talk, the researchers developed a method to determine the average cross-talk for an MPPC. The average value can then be subtracted from future experiments.

|

|

In one experiment, the researchers directed a weak laser beam at the MPPC. Based on known properties of photons in the laser, they were able to determine the cross-talk probability of the MPPC. In another experiment, the researchers used entangled photons instead of conventional light. Entangled photons form the basis of many quantum computing applications, and they induce a different MPPC response. Comparing the two experiments therefore allows a clear distinction between cross-talk effects caused by regular photons and those caused by entangled photons.

|

|

Most of the undesired crosstalk can be eliminated in this way, and enables a considerably more precise method of counting photons from quantum sources. "MPPCs are widely used in quantum optics, quantum computing and quantum cryptography," says Kalashnikov. "Moreover, they are extensively used in high-energy physics applications, such as the photosensors in scintillator detectors." The new MPPC counting method may be beneficial in a vast number of experiments involving the study of atomic–photon interfaces, as well as innovative applications in astronomy.

|