| Feb 09, 2006 |

Structure of a Molecular Scale Circuit Component

|

|

(Nanowerk News) At the U.S. Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory, researchers have determined the structure of an experimental, organic compound-based circuit component, called a "molecular electronic junction", that is only a few nanometers in dimension. This study may help scientists understand how the structure of molecular junctions relates to their performance and function and, in the longer term, may help incorporate these and other molecular-scale devices into a new generation of remarkably small electronics-based technologies.

|

|

The research is discussed in the article "Suspended Nanoporous Membranes as Interfaces for Neuronal Biohybrid Systems" the February 8, 2006, online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

|

|

"Molecular electronics is a very exciting developing field, since these extremely small circuits, based on organic molecules rather than metal, have a potentially greater circuit density than conventional silicon-based technology. This means that more circuits could fit on one circuit board, leading to electronic devices that are much smaller than those currently produced," said one of the study’s lead scientists, Brookhaven physicist Julian Baumert. "We’re interested in the structure of the junction — how the molecules are oriented and packed together — because it is linked to the function and performance of the circuit."

|

|

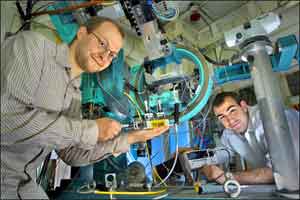

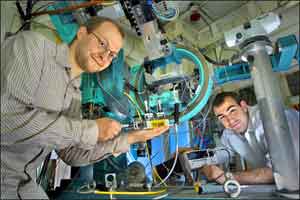

| Julian Baumert (left) and Michael Lefenfeld. (Source: BNL)

|

|

In conventional circuits, junctions are commonly made of two different types of silicon that, when layered together, allow electric current to flow in one direction only. Here, the junction under study consists of two very thin layers of two different organic compounds — "alkyl-thiol" and "alkyl-silane." They are sandwiched on one side by a layer of solid silicon and on the other side by a layer of liquid mercury, which serve as electrodes. Alkyl-thiol and alkyl-silane molecules have simple structures (making them fairly easy to study) and the potential to be good insulating materials (a desirable property in many junctions).

|

|

The scientists created the junctions by filling a small container with a drop of liquid mercury and depositing a very small amount of alkyl-thiol onto the mercury surface. They then topped the alkyl-thiol layer with an alkyl-silane-coated silicon wafer. This method yielded a junction with just a five-nanometer-thick gap between the two electrodes.

|

|

"This technique is not limited to simple alkane molecules," said Columbia University graduate student Michael Lefenfeld, the study’s second lead scientist. "

Many other types of organic molecules could be used, such as semi-conducting and conducting molecules. These materials also have a structure and packing density that plays a large role in their electrical performance."

|

|

The research group studied the junction at Brookhaven’s National Synchrotron Light Source, a facility that produces x-ray, ultraviolet, and infrared light for research. They aimed high-energy x-rays — energetic enough to penetrate the silicon wafer — at the junction from several incident angles and measured how the rays scattered off the organic molecules. Next, they attached electric contacts to the silicon and mercury electrodes and, for several different applied voltages, measured both the reflected x-ray signal and the electric current through the junction.

|

|

By analyzing the x-ray scattering data, the researchers discovered that the organic molecules are densely packed together, with most of the molecules positioned vertically. Further, the combination of the electric-current and x-ray measurements revealed that the current does not deform that structure, even when the applied voltage was very high. This implies that the molecular structure is quite stable.

|

|

"These are important details to know in order to fully understand the electronic properties of molecular-scale junctions," said Brookhaven Physicist Benjamin Ocko, one of the paper’s senior authors. "These investigation methods should be able to provide us with a better understanding of many other molecular junctions."

|