| Feb 29, 2024 |

Researchers find better way to handle hard-to-recycle material

|

|

(Nanowerk News) Glass fiber-reinforced plastic (GFRP), a strong and durable composite material, is widely used in everything from aircraft parts to windmill blades. Yet the very qualities that make it robust enough to be used in so many different applications make it difficult to dispose of ⎯ consequently, most GFRP waste is buried in a landfill once it reaches its end of life.

|

|

According to a study published in Nature Sustainability ("Flash upcycling of waste glass fiber-reinforced plastics to silicon carbide"), Rice University researchers and collaborators have developed a new, energy-efficient upcycling method to transform glass fiber-reinforced plastic (GFRP) into silicon carbide, widely used in semiconductors, sandpaper and other products.

|

|

“GFRP is used to make very large things, and for the most part, we end up burying the wing structures of airplanes or windmill blades from a wind turbine whole in a landfill,” said James Tour, the T.T. and W.F. Chao Professor and professor of chemistry and of materials science and nanoengineering. “Disposing of GFRP this way is just unsustainable. And until now there has been no good way to recycle it.”

|

|

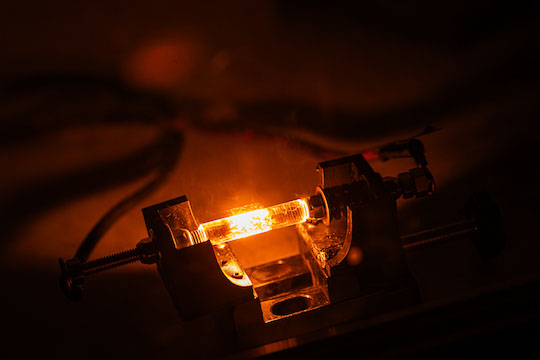

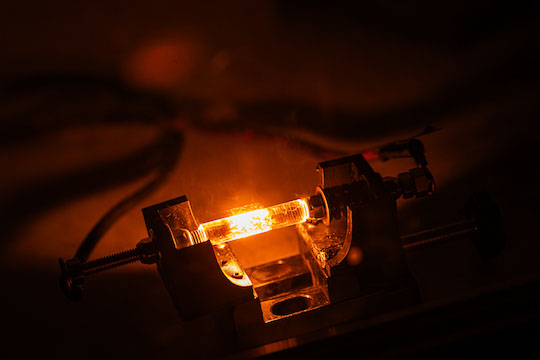

| Flash Joule heating is a technique that passes a current through a moderately resistive material to quickly heat materials to exceptionally high temperatures and transform them into other substances. (Photo by Jeff Fitlow, Rice University)

|

|

With increased pressure from regulatory agencies to revise and improve recycling practices for end-of-life vehicles, there is a strong need for better methods to manage GFRP waste. While some have tried to develop approaches using incineration or solvolysis to get rid of GFRP, Yi Cheng, a postdoctoral research associate and Rice Academy Junior Fellow who works in the Tour lab, said such processes are less than ideal because they are resource-intensive and result in environmental contamination.

|

|

“This material has plastic on the surface of glass fiber, and incinerating the plastic can generate a lot of toxic gases,” Cheng said. “Trying to dissolve GFRP is also problematic as it can generate a lot of acid or base waste from the solvents. We wanted to find a more environmentally friendly way to deal with this material.”

|

|

Tour’s lab has already made headlines for developing new waste disposal and recycling applications using flash Joule heating, a technique that passes a current through a moderately resistive material to quickly heat it to exceptionally high temperatures and transform it into other substances. Tour said when he learned of the issues involved with GFRP disposal from colleagues at the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, he thought that this kind of turbo-heating could transform GFRP into silicon carbide, widely used in semiconductors and sandpaper.

|

|

“We already knew that if we heat the mixture of metal chloride and carbon by flash Joule heating, we could get metal carbide ⎯ and in one demonstration, we made silicon carbide,” Tour said. “So we were able to leverage that work to come up with a process to transform GFRP into silicon carbide.”

|

|

This new process grinds up GFRP into a mixture of plastic and carbon and involves adding more carbon, when necessary, to make the mixture conductive. The researchers then apply high voltage to it using two electrodes, bringing its temperature up to 1,600-2,900 degrees Celsius (2,912-5,252 Fahrenheit).

|

|

“That high temperature facilitates the transformation of the plastic and carbon to silicon carbide,” Tour explained. “We can make two different kinds of silicon carbide, which can be used for different applications. In fact, one of these types of silicon carbide shows superior capacity and rate performance as battery anode material.”

|

|

While this initial study was a proof-of-concept test on a bench scale in the laboratory, Tour and colleagues are already working with outside companies to scale up the process for wider use. The operating costs to upcycle GFRP are less than $0.05 per kilogram, much cheaper than incineration or solvolysis ⎯ and more environmentally friendly.

|

|

It will take time ⎯ and some good engineering ⎯ to appropriately scale up this new flash upcycling method, Tour said. He said he is thrilled that his lab was able to develop a sustainable way to transform GFRP trash into silicon carbide treasure.

|

|

“This GFRP is a waste product which usually ends up in a landfill, and now you can turn it into a usable product that can help humankind,” he said. “This is exactly the kind of approach we need to support a circular economy. We need to find ways to take waste products from a wide variety of different applications and turn them into new products.”

|