| Jul 12, 2013 |

Using super-resolution microscopy to solve the structure of the nuclear pore complex

|

|

(Nanowerk News) Decade-old controversy over structure of nuclear pore solved, thanks to new method in which EMBL scientists combine thousands of super-resolution microscopy images to reach a precision below one nanometre.

|

|

It’s a parent’s nightmare: opening a Lego set and being faced with 500 pieces, but no instructions on how to assemble them into the majestic castle shown on the box. Thanks to a new approach by scientists at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Heidelberg, Germany, researchers studying large sets of molecules with vital roles inside our cells can now overcome a similar problem. In a study published online today in Science ("Nuclear Pore Scaffold Structure Analyzed by Super-Resolution Microscopy and Particle Averaging"), the scientists used super-resolution microscopy to solve a decade-long debate about the structure of the nuclear pore complex, which controls access to the genome by acting as a gate into the cell’s nucleus.

|

|

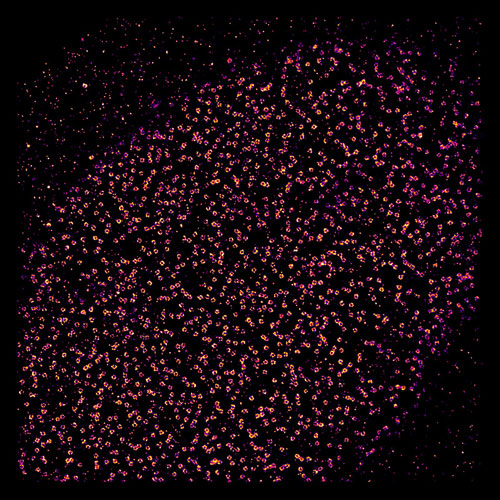

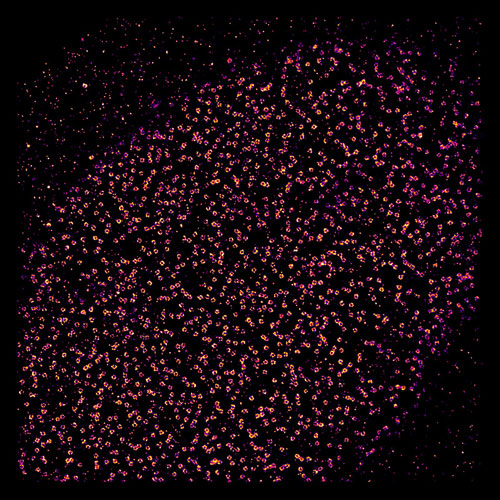

| At first glance, this may look like the latest view from a telescope, but it was taken by looking not out at the vastness of space, but into a human cell. What could pass for stars or distant galaxies are actually gates to the genome that is locked up inside the cell’s nucleus, as imaged by a super-resolution microscope. By combining images of thousands of these gates, called nuclear pore complexes, scientists at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Heidelberg, Germany, have solved a decade-old controversy over how the pieces that form each pore’s ring are arranged. (Credit: EMBL/A. Szymborska)

|

|

Like the flummoxed parent staring at the image on the box, scientists knew the gate’s overall shape, from electron tomography studies. And thanks to techniques like X-ray crystallography and single particle electron microscopy, they knew that the ring which studs the nucleus’ wall and controls what passes in and out is formed by sixteen or thirty-two copies of a Y-shaped building block. They even knew that each Y is formed by nine proteins. But how the Ys are arranged to form a ring was up for debate.

|

|

“When we looked at our images, there was no question: they have to be lying head-to-tail around the hole” says Anna Szymborska, who carried out the work.

|

|

To figure out how the Ys were arranged, the EMBL scientists used fluorescent tags to label a series of points along each of the Y’s arms and tail, and analysed them under a super-resolution microscope. By combining images from thousands of nuclear pores, they were able to obtain measurements of where each of those points was, in relation to the pore’s centre, with a precision of less than a nanometre. The result was a rainbow of rings whose order and spacing meant the Y-shaped molecules in the nuclear pore must lie in an orderly circle around the opening, all with the same arm of the Y pointing toward the pore’s centre.

|

|

Having resolved this decade-old controversy, the scientists intend to delve deeper into the mysteries of the nuclear pore – determining whether the circle of Ys is arranged clockwise or anticlockwise, studying it at different stages of assembly, looking at other parts of the pore, and investigating it in three dimensions.

|

|

“There’s been a lot of interest from other groups,” says Jan Ellenberg, who led the work, “so we’ll soon be looking into a number of other molecular puzzles, like the different ‘machines’ that allow a cell to divide, which are also built from hundreds of pieces.”

|

|

The work was carried out in collaboration with John Briggs’ group at EMBL, who helped adapt the image averaging algorithms from electron microscopy to super-resolution microscopy, and Volker Cordes at the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry in Göttingen, Germany, who provided antibodies and advice.

|