| Oct 17, 2017 |

Flexible 'skin' can help robots, prosthetics perform everyday tasks by sensing shear force

|

|

(Nanowerk News) If a robot is sent to disable a roadside bomb -- or delicately handle an egg while cooking you an omelet -- it needs to be able to sense when objects are slipping out of its grasp.

|

|

Yet to date it's been difficult or impossible for most robotic and prosthetic hands to accurately sense the vibrations and shear forces that occur, for example, when a finger is sliding along a tabletop or when an object begins to fall.

|

|

Now, engineers from the University of Washington and UCLA have developed a flexible sensor "skin" that can be stretched over any part of a robot's body or prosthetic to accurately convey information about shear forces and vibration that are critical to successfully grasping and manipulating objects.

|

|

The bio-inspired robot sensor skin, described in a paper published in Sensors and Actuators A: Physical ("Bioinspired flexible microfluidic shear force sensor skin"), mimics the way a human finger experiences tension and compression as it slides along a surface or distinguishes among different textures. It measures this tactile information with similar precision and sensitivity as human skin, and could vastly improve the ability of robots to perform everything from surgical and industrial procedures to cleaning a kitchen.

|

|

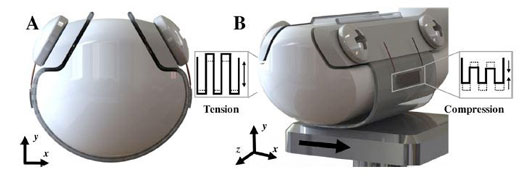

| The bio-inspired sensor skin developed by University of Washington and UCLA engineers can be wrapped around a finger or any other part of a robot or prosthetic device to help convey a sense of touch. (Image: UCLA Engineering)

|

|

"Robotic and prosthetic hands are really based on visual cues right now -- such as, 'Can I see my hand wrapped around this object?' or 'Is it touching this wire?' But that's obviously incomplete information," said senior author Jonathan Posner, a UW professor of mechanical engineering and of chemical engineering.

|

|

"If a robot is going to dismantle an improvised explosive device, it needs to know whether its hand is sliding along a wire or pulling on it. To hold on to a medical instrument, it needs to know if the object is slipping. This all requires the ability to sense shear force, which no other sensor skin has been able to do well," Posner said.

|

|

Some robots today use fully instrumented fingers, but that sense of "touch" is limited to that appendage and you can't change its shape or size to accommodate different tasks. The other approach is to wrap a robot appendage in a sensor skin, which provides better design flexibility. But such skins have not yet provided a full range of tactile information.

|

|

"Traditionally, tactile sensor designs have focused on sensing individual modalities: normal forces, shear forces or vibration exclusively. However, dexterous manipulation is a dynamic process that requires a multimodal approach. The fact that our latest skin prototype incorporates all three modalities creates many new possibilities for machine learning-based approaches for advancing robot capabilities," said co-author and robotics collaborator Veronica Santos, a UCLA associate professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering.

|

|

The new stretchable electronic skin, which was manufactured at the UW's Washington Nanofabrication Facility, is made from the same silicone rubber used in swimming goggles. The rubber is embedded with tiny serpentine channels -- roughly half the width of a human hair -- filled with electrically conductive liquid metal that won't crack or fatigue when the skin is stretched, as solid wires would do.

|

|

When the skin is placed around a robot finger or end effector, these microfluidic channels are strategically placed on either side of where a human fingernail would be.

|

|

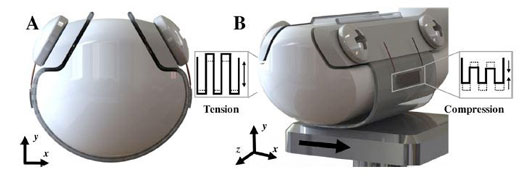

As you slide your finger across a surface, one side of your nailbed bulges out while the other side becomes taut under tension. The same thing happens with the robot or prosthetic finger -- the microfluidic channels on one side of the nailbed compress while the ones on the other side stretch out.

|

|

When the channel geometry changes, so does the amount of electricity that can flow through them. The research team can measure these differences in electrical resistance and correlate them with the shear forces and vibrations that the robot finger is experiencing.

|

|

| As the robot finger slides along a surface, serpentine channels filled with electrically conductive liquid metal and embedded in the rubber skin stretch on one side of the finger and compress on the other. This changes the amount of electricity that can flow through the channels, which can be measured and correlated with shear force and vibration. (Image: UCLA Engineering)

|

|

"It's really following the cues of human biology," said lead author Jianzhu Yin, who recently received his doctorate from the UW in mechanical engineering. "Our electronic skin bulges to one side just like the human finger does and the sensors that measure the shear forces are physically located where the nailbed would be, which results in a sensor that performs with similar performance to human fingers."

|

|

Placing the sensors away from the part of the finger that's most likely to make contact makes it easier to distinguish shear forces from the normal "push" forces that also occur when interacting with an object, which has been difficult to do with other sensor skin solutions.

|

|

The research team from the UW College of Engineering and the UCLA Henry Samueli School of Engineering and Applied Science has demonstrated that the physically robust and chemically resistant sensor skin has a high level of precision and sensitivity for light touch applications -- opening a door, interacting with a phone, shaking hands, picking up packages, handling objects, among others. Recent experiments have shown that the skin can detect tiny vibrations at 800 times per second, better than human fingers.

|

|

"By mimicking human physiology in a flexible electronic skin, we have achieved a level of sensitivity and precision that's consistent with human hands, which is an important breakthrough," Posner said. "The sense of touch is critical for both prosthetic and robotic applications, and that's what we're ultimately creating."

|