| Oct 23, 2013 |

Martian meteorite may hold secret to slowing global warming

|

|

(Nanowerk News) A team of researchers including Museum meteorite curator Dr Caroline Smith, studied a Martian meteorite from the Museum’s collections and discovered evidence of ‘carbonation’, a process that removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and locks it away in rocks. Their paper is published today in Nature Communications.

|

|

Carbonation occurs when certain minerals in rocks react with water and carbon dioxide in the atmosphere to form new minerals. Carbon dioxide contributes to the greenhouse effect, trapping heat within the atmosphere of a planet.

|

|

The early Martian atmosphere was dense with high levels of carbon dioxide, creating a warmer, wetter planet than the one we see today. Mars now has less carbon dioxide and average temperatures of around -55 degrees C.

|

|

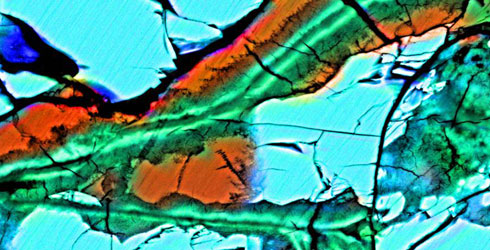

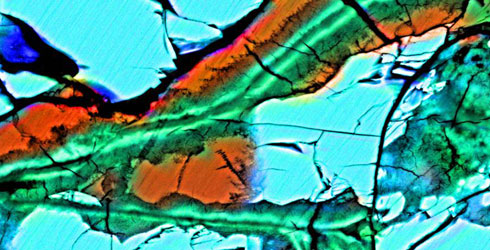

| False colour image of the Lafayette meteorite from a scanning electron microscope showing evidence of carbonation, where olivine (blue) has reacted with water and atmospheric carbon dioxide to be replaced by carbon-rich siderite (orange) (© SUERC, University of Glasgow.)

|

|

First proof of Martian carbonation

|

|

The new study, led by University of Glasgow geoscientist Dr Tim Tomkinson, shows the first direct evidence of carbonation on Mars. The meteorite, named Lafayette and discovered in the USA in 1931, is around 1.3 billion years old.

|

|

The team discovered that the meteorite contains the carbonate mineral siderite, which formed when the silicate mineral olivine reacted with water and atmospheric carbon dioxide.

|

|

This reaction occurs naturally today on Earth, but the atmospheres of Earth and Mars are very different.

|

|

Earth’s atmosphere is about 21 per cent carbon dioxide, whereas Mars’ is around 96 per cent. Mars’ atmosphere used to be much denser, but it is now only a thin layer.

|

|

With so much carbon dioxide available for the mineral reaction in the early Martian atmosphere, the researchers believe enough was locked away to cause the atmosphere to thin, leading to planet-wide cooling.

|

|

‘To look at a sample under the microscope and see a process that can act on a planetary scale – that’s incredible,’ said Smith.

|

|

Trapping carbon inside rocks

|

|

The mineral reaction is being investigated as a potential solution to climate change on Earth, by capturing carbon dioxide emanating from power plants and trapping it in nearby rock formations.

|

|

The magnitude with which the reaction took place on Mars indicates it could be effective on a planetary scale.

|

|

‘This discovery is both significant in terms of the way in which scientists will study Mars in the future but also to providing us with vital clues to how we can limit the accumulation of carbon dioxide in the Earth’s atmosphere and so reduce climate change,’ said Tomkinson.

|

|

More missions to Mars

|

|

Before Mars began cooling around 4 billion years ago, it is thought that the atmosphere was much thicker and there was liquid water at the planet's surface. There is only one Martian meteorite from this time period, and it has a different composition than the Lafayette meteorite, so it's difficult to know if the same carbonation reaction occurred back then.

|

|

However, the study’s findings are backed up by remote sensing data collected by space missions, which show a close relationship between the presence of carbonate-bearing and olivine-rich rocks in a region of Mars called Nili Fossae.

|

|

‘Martian meteorites have provided us with a wealth of information about the geological history of the planet,’ said meteorite curator Smith. ‘Our next stage in the exploration of Mars is to send technologically advanced rovers that can help us to understand the context of the rocks and then return samples for detailed study in laboratories on Earth’. She is currently working with European and UK space agencies to plan and prepare for samples returned to Earth by space missions to Mars in the next few decades.

|