| May 12, 2015 |

Probing the secrets of the universe inside a metal box

|

|

(Nanowerk News) The Standard Model of particle physics, sometimes called "The Theory of Almost Everything," is the best set of equations to date that describes the universe's fundamental particles and how they interact. Yet the theory has holes -- including the absence of an adequate explanation for gravity, the inability to explain the asymmetry between matter and antimatter in the early universe, which gave rise to the stars and galaxies, and the failure to identify fundamental dark matter particles or account for dark energy.

|

|

Researchers now have a new tool to aid in the search for physics beyond the good, but yet incomplete Standard Model. An international team of scientists has designed and tested a magnetic shield that is the first to achieve an extremely low magnetic field over a large volume. The device provides more than 10 times better magnetic shielding than previous state-of-the art shields. The record-setting performance makes it possible for scientists to measure certain properties of fundamental particles at higher levels of precision -- which in turn could reveal previously hidden physics and set parameters in the search for new particles.

|

|

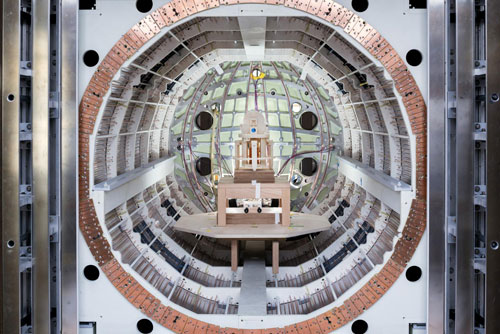

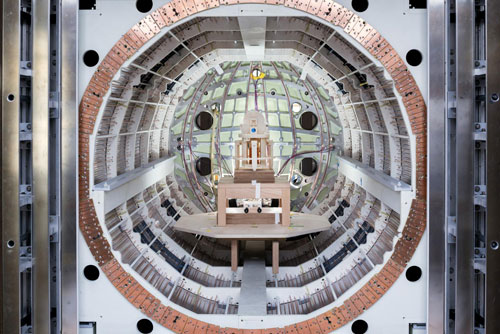

| This image shows the inner three layers of the magnetic shield (also known as the insert), and the cylindrical layer with 780 copper rods. The cylindrical layer is used to generate a very uniform magnetic field, which is necessary for EDM experiments. Also shown are two measurement devices: A mercury magnetometer is placed between the wooden support structure, and a high precision pendulum device, which is used for the absolute alignment of conventional magnetic field probes, is on top of the support table. (Image: Technische Universität Müchen)

|

|

The researchers describe the new magnetic shield in a paper in the Journal of Applied Physics ("A large-scale magnetic shield with 106 damping at millihertz frequencies"), from AIP Publishing.

|

|

High precision measurements are one of three frontiers to search for physics beyond the Standard Model, explained Tobias Lins, a doctoral student who worked on the new magnetic shield in the research lab of Professor Peter Fierlinger at the Technische Universität München in Germany. The precision measurements complement other methods to search for new physics, including slamming particles together in a collider to generate new, high-energy particles, and peering into space to catch signals from the early universe.

|

|

"Precision experiments are able to probe nature up to energy scales which might not be accessible by current and next generation collider experiments," Lins said. That's because the existence of exotic new particles can slightly alter the properties of already known particles. A tiny deviation from the expected properties may indicate that an as-yet-undiscovered fundamental particle inhabits the "particle zoo."

|

|

Constructing the Shield

|

|

The researchers built the new shield out of several layers of a special alloy, composed of nickel and iron, that has a high degree of magnetic permeability -- meaning it can act like a sponge to absorb and redirect an applied magnetic field, like the earth's own magnetic field or fields generated by equipment such as motors and transformers.

|

|

"The apparatus might be compared to cuboid Russian nesting dolls," Lins said. "Like the dolls, most layers can be used individually and with an increasing number of layers the inside is more and more protected."

|

|

The team's big breakthrough came from in-depth numerical modeling of the arrangement of the precision treated magnetizable alloy, resulting in significantly optimized design details, like thickness, connections and spacing of layers.

|

|

The materials in magnetic shields change their magnetization due to environmental influences, like temperature changes and vibrations caused by passing cars, and these shifts can be passed to the inside of the shield. The thinner sheets in the new design enabled a better balancing of the magnetic field in the metal, resulting in the smallest and most homogenous magnetic field ever created within the shielded space, even beating the average ambient magnetic field of the interstellar medium.

|

|

New Experiments Ahead

|

|

Plans are already underway to use the new magnetic shield in an experiment to test limits for the distribution of charges (called the electric dipole moment, or EDM) of an isotope of xenon. An EDM that is higher than predicted by the Standard Model could signal the existence of a new particle whose mass is linked to the amount by which the EDM deviates from the expected value.

|

|

The researchers also want to use a modified SQUID detector -- which can detect extremely subtle magnetic fields -- to search for long theorized, but never detected magnetic monopoles. Within the magnetically quiet space inside the shield, a monopole passing by the SQUID might produce a magnetic field higher than the background noise level, Lins said.

|