| Oct 27, 2017 |

Scientist devises a solar reactor to make water and oxygen from moon rocks

|

|

(Nanowerk News) Thorsten Denk's paper Design and Test of a Concentrated Solar Powered Fluidized Bed Reactor for Ilmenite Reduction (pdf) was presented at the 23rd Annual SolarPACES Conference in Chile.

|

|

Working over a ten year period at the Plataforma Solar de Almeria (CIEMAT) Denk has designed and built a device to make enough oxygen and water for 6 to 8 astronauts, powered by a thermal solar reactor. In 2017 it completed a six-month test run.

The idea is not new; just the implementation.

|

|

| An aerospace engineer has built a device to make water and oxygen from the lunar regolith, powered by solar energy. (Image: Thorsten Denk)

|

|

"From the beginning people were thinking this probably has to be done with a solar furnace, because on the Moon there is not very much to heat a system that you can use; photovoltaics with electricity or a nuclear reactor or concentrated solar radiation," said Denk, who has experience in concentrating solar and in particles engineering.

|

|

"After the Apollo missions, scientists had a lot of ideas of how to make oxygen on the Moon, because every material that you bring from Earth costs money. For every kilogram of payload you need hundreds of kilograms of fuel."

|

|

Denk's simple solar reactor could chemically split water from lunar soil, and electrolysis could then split the H2O into oxygen and hydrogen. But few other attempts used solar reactors, and ones that did had flawed designs, due to undersizing the solar concentrator to heat the reactor - and none exceeded bench scale.

|

|

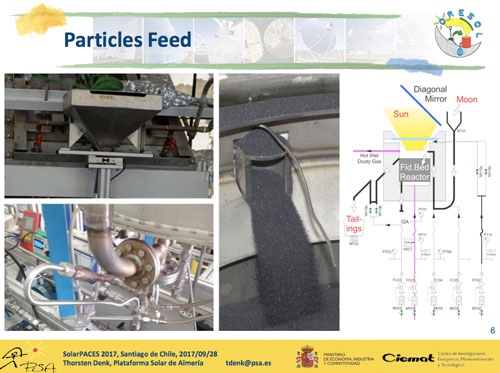

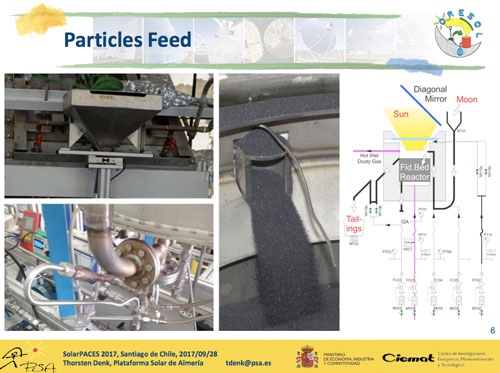

"Mine is the real size you would build on the Moon to make oxygen for a crew of six or eight, so there's no upscaling needed later. I have also extended my use of fluidized beds. It's not only the reactor itself, but it is also the supply lines and the removal pipe for the particles," said Denk of his fluidized bed solar reactor design. In a fluidized bed reactor, particles behave like liquid.

|

|

"It looks just like boiling liquid. If you look up close you see it move very wildly and the same thing happens with fluidized particles. So you have very good mixing and very good contact between the particles and the gas. The result is a very homogeneous temperature and efficient chemistry," he explained.

|

|

| The regolith would need pre-treatment to smooth the particles out, because unlike rounded particles weathered by atmosphere and water on Earth, lunar regolith particles are strange shapes with sharp edges, as there's no atmosphere on the Moon to wear them down. Pretreating them "round" then sieving for the correct fraction of the grain size would be critical for the safe operation of the fluidized bed reactor. (click on image to enlarge)

|

|

Denk was initially inspired by a NASA Centennial challenge in 2008 for oxygen from Moon rock. "They put all the questions that they have but they have no money to answer them to the public and if you succeed you can win $2 million." The weight limit was so low, 50 kg, that NASA's challenge expired with no takers. Denk's can process 25 kg of particle load in less than an hour and currently weighs 400 kg. He thinks he can reduce the weight.

|

|

But, ten years later, he has met the two other conditions: that it could produce 2.5 kg of oxygen in four hours, and that electricity use should not surpass 10 kW. The chemical reaction is mostly powered by the solar reactor, and would use less than 5 kW of electricity, mostly for the second step; splitting oxygen from hydrogen with electrolysis.

|

|

He has demonstrated the first step, making 700 g of water in one hour - which would enable making 2.5 g of oxygen in 4 hours using electrolysis, a proven technology, but that will need additional funding.

|

|

Water produced in a solar reactor for the MoonWith the successful test of this solar reactor design, Denk has achieved the first step, creating H2O on the Moon using solar thermal energy. For the second step, solar electrolysis would break the H2O into hydrogen and oxygen.

|

|

His process uses ilmenite (TiO3), an iron oxide found in the "dark" areas of the Moon. It would be dug up by a small robot and carried to the reactor. Denk likes the Rassor digging robot, with opposing rotating drums that prevent it from propelling off-surface by the force of digging in lunar gravity (one-sixth Earth gravity).

|

|

How this would split H2O and oxygen from lunar soil:

|

|

The chemical reactions to make oxygen and water would involve one import from Earth, hydrogen; but just initially.

|

|

"The hydrogen would be just for the first few hours. Then that would be recycled with the electrolyzer," he explained. "Even if you bring hydrogen from Earth and get oxygen from the Moon for making rocket fuel, you save nearly 90% of the weight. Hydrogen is the lightest element. Oxygen is much heavier."

|

He described the two-step process

|

|

The main component is the iron-titanium oxide - ilmenite (FeTiO3). To remove the oxygen, you add hydrogen so it becomes water. H2O comes out of the first step. FeTiO3 + H2 + solar heat → Fe + TiO2 + H2O.

|

|

The second step is in an electrolyzer using the product water from the reactor. The water is split to produce hydrogen and oxygen. H2O + electric power → H2 + ½O2.

|

|

The oxygen is the product and the hydrogen gets returned to the process.

|

The Moon's ideal solar resource

|

|

The Moon has ideal conditions for making solar fuels, because chemical reactions to split oxygen and hydrogen require very high temperatures, and work best when they are continuous. The Moon's annual normal solar irradiation is nearly 6,000 kWh per square meter per year, and lunar days are 14 earth-days long; 354 hours.

|

|

"Daylight is 2 weeks without interruption, and then you have the same half-month of dark as night. So if you need three hours to turn it on, it's not a big problem. There is no atmosphere on the Moon, and there is no weather, no clouds, so you really can operate from sunrise to sunset at full power for each half-month," Denk said.

|

|

Concentrated solar furnaces are able to achieve very high temperatures. But at above 1050?C, the Moon's regolith particles tended to gum up the works by glueing together; a process called sintering.

|

|

"The chemical reaction starts to be working from 800?C but sintering starts to be a problem at 1,050?C degrees, so my goal was not to surpass the 1000?C," he explained. "I achieved a bit more than 970?C and the maximum was hardly above 1000?C. So I had a temperature in the bed of not more than 30? up and down, for the highest possible average temperature without sintering."

|

|

With the successful test of this solar reactor design, Denk has achieved the first step, creating H2O on the Moon using solar thermal energy. For the second step, solar electrolysis would break the H2O into hydrogen and oxygen.

|