| Nov 27, 2017 |

Hubble and Gaia team up to measure 3-D stellar motion with record-breaking precision

|

|

(Nanowerk News) A team of astronomers used data from both the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope and ESA's Gaia satellite to directly measure the 3D motions of individual stars in a nearby galaxy. The achieved accuracy is better than anything previously measured for a galaxy beyond the Milky Way. The motions provide a field test of the currently-accepted cosmological model and also measure the trajectory of the galaxy through space. The results are published in Nature Astronomy ("3D motions in the Sculptor dwarf galaxy as a glimpse of a new era").

|

|

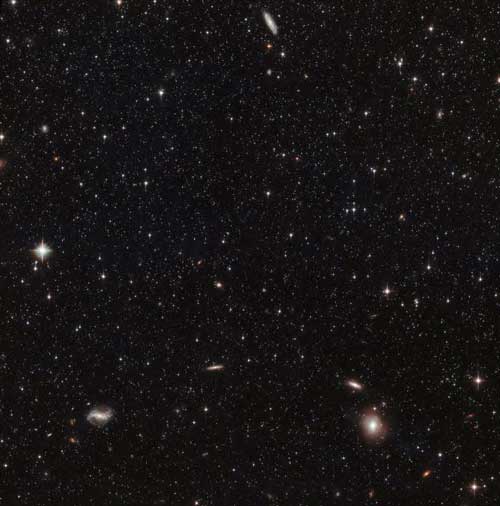

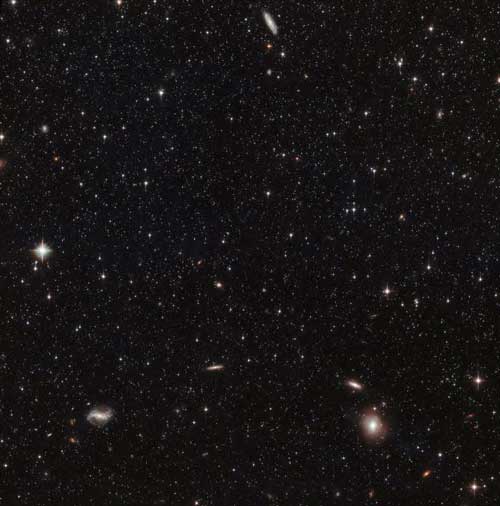

Astronomers from the Kapteyn Astronomical Institute and Leiden Observatory, both in the Netherlands, used data from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope and ESA's Gaia space observatory to measure the motions of stars in the Sculptor Dwarf Galaxy. The Sculptor Dwarf is a satellite galaxy orbiting the Milky Way, 300 000 light-years away from Earth.

|

|

| This image shows a small part of the Sculptor Dwarf Galaxy, a satellite galaxy of the Milky Way, situated only about 300,000 light-years away from Earth. This is one of two different pointings of the telescope that were used in a study combining data from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope and ESA's Gaia satellite to measure the 3-D motion of stars in this galaxy. (Image: ESA/Hubble & NASA)

|

|

Only by combining the datasets from these two successful ESA missions -- produced more than 12 years apart -- could the scientists directly measure the exact 3D motions of stars within the Sculptor Dwarf Galaxy [1]. The is the first time this has been achieved with such accuracy for a galaxy other than the Milky Way [2].

|

|

Davide Massari, lead author of the study, describes the precision of the research: "With the precision achieved we can measure the yearly motion of a star on the sky which corresponds to less than the size of a pinhead on the Moon as seen from Earth." This kind of precision was only possible due to the extraordinary resolution and accuracy of both instruments. Also the study would not have been possible without the large interval of time between the two datasets which makes it easier to determine the movement of the stars.

|

|

The Sculptor Dwarf Galaxy is a dwarf spheroidal galaxy, which are among the most dark matter dominated objects in the Universe. This makes them ideal targets for investigating the properties of dark matter. In particular, understanding how dark matter is distributed in these dwarf galaxies allows astronomers to test the validity of the currently-accepted cosmological model. However, dark matter cannot be studied directly.

|

|

"One of the best ways to infer the presence of dark matter is to examine how objects move within it," explains Amina Helmi, co-author of the paper. "In the case of dwarf spheroidals, these objects are stars."

|

|

The information gathered about the 3D motion of stars in the Sculptor Dwarf Galaxy can be translated directly into knowledge of how its total mass -- including dark matter -- is distributed. The new results show that stars in the Sculptor Dwarf Galaxy move preferentially on elongated radial orbits. This indicates that the density of dark matter increases towards the centre instead of flattening out. These findings are in agreement with the established cosmological model and our current understanding of dark matter, taking into account the complexity of Sculptor's stellar populations.

|

|

As a side effect of the study, the team also presented a more accurate trajectory of the Sculptor Dwarf Galaxy as a whole as it orbits the Milky Way. Their results show that it is moving around the Milky Way in a high-inclination elongated orbit that takes it much further away than previously thought. Currently, it is nearly at its closest point to the Milky Way, but its orbit can take it as far as 725 000 light-years away.

|

|

"With these pioneering measurements, we enter an era where measuring 3D motions of stars in other galaxies will become routine and will be possible for larger star samples. This will mostly be thanks to ESA's Gaia mission," concludes Massari.

|