| Sep 19, 2018 |

ExoMars highlights radiation risk for Mars astronauts, and watches as dust storm subsides

|

|

(Nanowerk News) Astronauts on a mission to Mars would be exposed to at least 60% of the total radiation dose limit recommended for their career during the journey itself to and from the Red Planet, according to data from the ESA-Roscosmos ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter being presented at the European Planetary Science Congress, EPSC, in Berlin, Germany, this week.

|

|

The orbiter’s camera team are also presenting new images of Mars during the meeting. They will also highlight the challenges faced from the recent dust storm that engulfed the entire planet, preventing high-quality imaging of the surface.

|

|

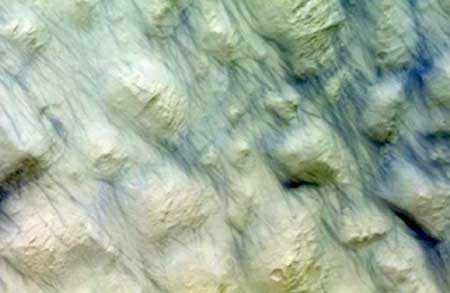

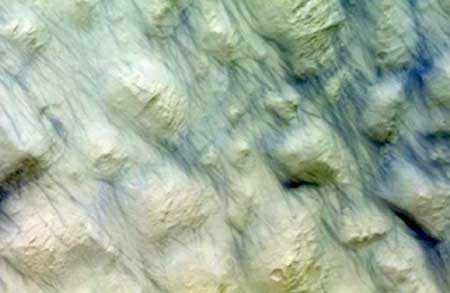

| Dust devils on Mars. The Colour and Stereo Surface Imaging System, CaSSIS, onboard the joint ESA-Roscosmos ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter imaged the Ariadne Colles region at 34ºS on 2 September 2018. The image shows an unusual terrain type – sometimes referred to as chaotic blocks – but what is particularly striking are the large number of dark streaks. One possible interpretation is that these features were produced during the recent dust storm: they could have resulted from dust devils stirring up the surface dust. (Image: ESA/Roscosmos/CaSSIS, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO)

|

Radiation monitoring

|

|

The Trace Gas Orbiter began its science mission at Mars in April, and while its primary goals are to provide the most detailed inventory of martian atmospheric gases to date – including those that might be related to active geological or biological processes – its radiation monitor has been collecting data since launch in 2016.

|

|

The Liulin-MO dosimeter of the Fine Resolution Epithermal Neutron Detector (FREND) provided data on the radiation doses recorded during the orbiter’s six-month interplanetary cruise to Mars, and since the spacecraft reached orbit around the planet.

|

|

On Earth, a strong magnetic field and thick atmosphere protects us from the unceasing bombardment of galactic cosmic rays, fragments of atoms from outside our Solar System that travel at close to the speed of light and are highly penetrating for biological material.

|

|

In space this has the potential to cause serious damage to humans, including radiation sickness, an increased lifetime risk for cancer, central nervous system effects, and degenerative diseases, which is why ESA is researching ways to best protect astronauts on long spaceflight missions.

|

|

The ExoMars measurements cover a period of declining solar activity, corresponding to a high radiation dose. Increased activity of the Sun can deflect the galactic cosmic rays, although very large solar flares and eruptions can themselves be dangerous to astronauts.

|

|

“One of the basic factors in planning and designing a long-duration crewed mission to Mars is consideration of the radiation risk,” says Jordanka Semkova of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences and lead scientist of the Liulin-MO instrument.

|

|

“Radiation doses accumulated by astronauts in interplanetary space would be several hundred times larger than the doses accumulated by humans over the same time period on Earth, and several times larger than the doses of astronauts and cosmonauts working on the International Space Station. Our results show that the journey itself would provide very significant exposure for the astronauts to radiation.”

|

|

The results imply that on a six-month journey to the Red Planet, and assuming six-months back again, an astronaut could be exposed to at least 60% of the total radiation dose limit recommended for their entire career. |

|

The ExoMars data, which is in good agreement with data from Mars Science Laboratory’s cruise to Mars in 2011–2012 and with other particle detectors currently in space – taking into account the different solar conditions – will be used to verify radiation environment models and assessments of the radiation risk to the crewmembers of future exploration missions.

|

|

A similar sensor is under preparation for the ExoMars 2020 mission to monitor the radiation environment from the surface of Mars. Arriving in 2021, the next mission will comprise a rover and a stationary surface science platform. The Trace Gas Orbiter will act as a data relay for the surface assets.

|

Global dust storm subsides

|

|

Radiation is not the only hazard facing Mars missions. A global dust storm that engulfed the planet earlier this year resulted in severely reduced light levels at the surface, sending NASA’s Opportunity rover into hibernation. The solar-powered rover has been silent for more than three months.

|

|

Orbiting 400 km above the surface, the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter’s Colour and Stereo Surface Imaging System, CaSSIS, has also suffered. Because the surface of the planet was almost totally obscured by dust, the camera was switched off for much of the storm period.

|

|

“Normally we don’t like to release images like this, but it does show how the dust storm prevents useful imaging of the surface,” says the camera’s Principal Investigator, Nicolas Thomas from the University of Bern. “We had images that were worse than this when we took an occasional look at the conditions, and it didn’t make too much sense to try to look through ‘soup’.”

|

|

But the camera team discovered that even a dust cloud has a silver lining.

|

|

“The dust-obscured observations are actually quite good for calibration,” says Nicolas. “The camera has a small amount of straylight and we have been using the dust storm images to find the source of the straylight and begin to derive algorithms to remove it.”

|

|

Since 20 August, CaSSIS has started round-the-clock imaging again.

|

|

“We still have some images affected by the dust storm but it is quickly getting back to normal and we have already had a lot of good quality images coming down since the beginning of September,” adds Nicolas.

|

|

One image acquired on 2 September, although not completely free from artefacts, shows striking dark streaks that might be linked to the storm itself. A possible interpretation is that these features were produced by ‘dust devils’ – whirlwinds – stirring up loose surface material. The region, Ariadne Colles in the southern hemisphere of Mars, was imaged by NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter camera in March, before the storm, and there seemed to be little evidence of these streaks.

|

|

“We are very excited to be discussing some of the first scientific results from the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter at EPSC this week, as well as the progress of the upcoming surface mission,” says Håkan Svedhem, ESA’s Trace Gas Orbiter project scientist.

|

|

“While our instrument teams are working hard analysing the details of the atmospheric gas inventory and preparing these results for publication, we are certainly pleased to already be able to contribute to topical discussions on the dust storm and on issues that are essential for future crewed missions to Mars.”

|